Photo: Wikimedia Commons

If the 5-foot-3-inch Margaret Atwood were to stand on all the fiction, poetry, social history, criticism, and children’s books she’s written in the past 30 years, she’d be a literal — not just literary — giant. Atwood, whose novels include The Handmaid’s Tale, Cat’s Eye, and her latest, Alias Grace, is known for her wicked sense of humor and caustic tongue, which have inspired critics to label her “Medusa,” “amusing duchess,” and “quiet Mata Hari.”

The 57-year-old Toronto-based storyteller has wielded her pen and activist voice on behalf of many causes. She is the former president of PEN (Poets, Essayists, Novelists) Canada, which assists writers worldwide who live under political oppression. Most recently, Atwood protested plans to turn Toronto into a “megacity,” in which the metropolitan area’s six municipal governments would be consolidated into one governing board. In Atwood’s world, whether she’s aiming at the premier of Ontario or the not-so-nice girls in Cat’s Eye, no one gets off easy.

Q: How does your political involvement inform your creative process?

A: I have no idea. People talking about politics usually start from the ass end backwards in that they think you have a political agenda, and then you make your work fit that cookie cutter. It’s the other way around. One works by simple observation, looking into things. It’s usually called insight and out of that comes your view — not that you have the view first and then squash everything to make it fit. I’m talking about staying out of the Procrustean bed. You know the myth: Everybody had to fit into Procrustes’ bed and if they didn’t, he either stretched them or cut off their feet. I’m not interested in cutting the feet off my characters or stretching them to make them fit my certain political view.

Q: So, do your political self and your creative self communicate at all?

A: As an artist your first loyalty is to your art. Unless this is the case, you’re going to be a second-rate artist. I don’t mean there’s never any overlap. You learn things in one area and bring them into another area. But giving a speech against racism is not the same as writing a novel. The object is very clear in the fight against racism; you have reasons why you’re opposed to it. But when you’re writing a novel, you don’t want the reader to come out of it voting yes or no to some question. Life is more complicated than that. Reality simply consists of different points of view.

When I was young I believed that “nonfiction” meant “true.” But you read a history written in, say, 1920 and a history of the same events written in 1995 and they’re very different. There may not be one Truth — there may be several truths — but saying that is not to say that reality doesn’t exist.

When I wrote Alias Grace, for example, about Canada’s famous 19th-century convicted murderer Grace Marks, I knew there were some things that weren’t true about this historical figure. After all my research, I still do not know who killed Thomas Kinnear and his housekeeper, Nancy Montgomery. Someone killed them. To say that we don’t know exactly who did it is not to say that nobody killed them. There is a truth in their deaths, but some other truths — such as who really did the killing — are not knowable.

Q: But are there certain discrete truths that you explore in your work? So often people on the left seem afraid to talk about transcendent truths, values, the ethics involved in even the smallest human interactions.

A: I’m probably not exactly on the left in the way that you understand it.

Q: How would you define yourself then?

A: I’m a Red Tory. To get a fix on this category, you have to go back to the 19th century. The Tories were the ones who believed that those in power had a responsibility to the community, that money should not be the measure of all things.

Q: Would this be your discrete truth — that money is not the measure of all things?

A: Everybody knows it isn’t. Within one’s own family money is not the measure of things, unless the person is an absolute Scrooge. Only the most extreme kind of monster would put a price on everything. There are all kinds of other things that we are not supposed to sell — political influence being one of them. We too rarely have public conversations about the common sense of money. We too rarely talk about the human cost of putting some of these economic measures into effect.

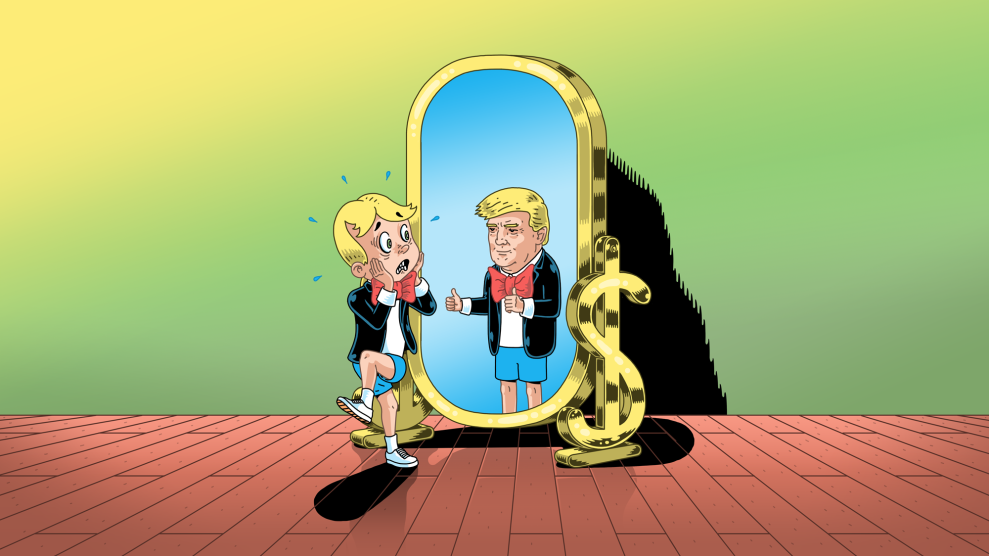

Q: What you’re saying sounds great, but we live in a consumerist culture where money is the measure of who you are.

A: Well, it used to be that your bloodlines dictated who you were. But the U.S. became the land of the self-made man, in which not only did you make a fortune but you could make up everything else about yourself as well. You move into a new town with a spurious pedigreed background and you just make yourself up.

I collect con-artist stories. One of my favorites is that of a Portuguese woman who had been passing herself off not only as a man but in the military establishment as a general. Then there was the jazz musician who was married and had three adopted children and turns out to have been a woman all along.

Q: Why do you think these women do it? For the power they gain by being men?

A: Sometimes it’s not even power so much as the absence of nonpower, which is different. One actively exercises power. The absence of nonpower is just that people don’t bother you. You don’t suffer the consequences of not being powerful.

Q: In much of your writing you explore the state of the — I don’t want to say “victim” — of the person who is “not yet,” and mostly these are women.

A: You know why? Unless something has gone disastrously wrong, other people aren’t that interesting to write about. Let me tell you a story: When my daughter was little, she and a friend decided to put on a play. It opened with two characters having breakfast. They had some orange juice and cornflakes and they poured milk on the cornflakes and they had some tea and they had some coffee and they had some more orange juice and cornflakes and toast and they put jam on the toast. Finally we said, is anything else going to happen in this play other than having breakfast, and they said no, and we said, well then, it’s time to go.

This is lesson No. 1 in narrative: Something has to happen. It can be good people to whom bad things happen, a nice person getting bitten in two by a shark or crushed by an earthquake, or their husbands run off on them.

Or then it can be people of devious or shallow character getting into trouble or making trouble. But if you want to read a novel in which nice people do nothing but good things, I recommend Samuel Richardson’s The History of Sir Charles Grandison. It goes on and on. I think I’m the only person who’s ever actually finished the book.

Q: I wasn’t arguing for the crushingly boring novel. My question was about victimhood. Does this mean all your books need female victims?

A: Let us change it from victimhood to people in circumstances that put some pressure on them, which is not quite the same thing. Some people tell me that Grace Marks is a victim and I say, “Hey, just hang on a minute. What about Nancy and Thomas? They’re the ones who ended up dead in the cellar.” I don’t think it’s quite as simple as “These people over here are always the oppressors, and these people over here are always victims.”

Q: You turn the traditional victim into victimizer to chilling effect in Cat’s Eye, where little girls are anything but sugar and spice and everything nice.

A: Of course, I wasn’t supposed to say that, because sisterhood is powerful and women are always supposed to get along with one another. It’s not true any more than it is for men — and why should it be?

Women are human beings, and human beings are a very mixed lot. I’ve always been against the idea that women were Victorian angels, that they could do no wrong. I’ve always thought it was horseshit and does nobody any good. Remember, Lizzie Borden got off largely because the cultural agenda had convinced people that women were morally superior to men, so Lizzie Borden was “incapable” of taking the ax and giving her mother 40 whacks.

In the early fight for women’s rights, the point was not that women were morally superior or better. The conversation was about the difference between men and women — power, privilege, voting rights, etc. Unfortunately, it quickly moved to the “women are better” argument. If this were true in life or in fiction, we wouldn’t have any dark or deep characters. We wouldn’t have any Salomes, Carmens, Ophelias. We wouldn’t have any jealousy or passion.