Photos: Hickey-Robertson Photography

Notwithstanding the recently renewed peace efforts between Palestinian and Israeli leaders in the Middle East, it is still difficult to discuss the conflict openly here in the United States. It was only recently that Joseph Massad, a Palestinian-American professor at Columbia University, came under fire for being “anti-Israel.” As it turned out, an ensuing investigation cleared Massad of all changes but one: the professor had become “angered at a question that he understood to countenance Israeli conduct of which he disapproved and… responded quite heatedly.” Was Massad acting intemperately? Perhaps. But the larger issue here is that the question of Palestine has become so difficult to discuss, so thoroughly politicized, that anyone who acknowledges the existence and mistreatment of Palestinians is seen as either sanctioning terrorism, or being anti-Semitic, or both. So long as this view prevails, there will be no hope of any meaningful discussion of the conflict.

One person who recently got to see this chilling effect up close is James Harithas, an art curator in Houston. Harithas’ gallery, the Station Museum, had displayed a Palestinian art show, “Made in Palestine” that opened in May of 2003. The exhibit contained work from a variety of Palestinian artists—from photos of “martyr billboards” in Gaza to ceramic olive trees—that was both deeply personal and inherently political. Originally, the exhibit was only supposed to run for three months, but Harithas extended this a further three months, into October, as it drew thousands of people from across Houston. One of the curator’s closest friends, a Jewish man, came to see the exhibit. “I could see how hard it was for him,” said Harithas, “But it really moved him. Now he’s handing out the [‘Made In Palestine’ catalogue] to his relatives.” Finally, after receiving some 20,000 visits to the museum, he felt it was time to move the exhibit to another city.

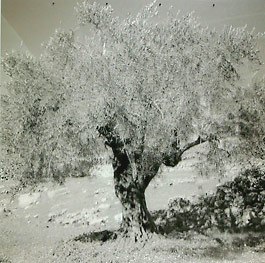

“Tale of a Tree,” by Vera Tamari. View a larger version

That’s when Harithas hit a wall. As he told al-Jazeerah, “I thought I had enough contacts to get this exhibit shown in museums across the nation, but I found out that even people who I considered close contacts said off-the-record they would lose their museum funding if they were to hold an exhibit that was pro-Palestinian.” It is clear that “pro-Palestinian” has a negative connotation here in the United States. The implication is that the term denotes anti-Israelism, which is, in turn, a short hop away from anti-Semitism. Alternatively, “pro-Palestinian” implies “pro-terrorist.” But it’s important to note that nowhere does the “Made in Palestine” exhibit claim to be “pro-Palestinian,” or to support terrorism, or to persuade people to become anti-Semites. It simply puts forth contemporary Palestinian art, the sort found in any other art exhibit, from images burnt in wood depicting the life of one artist’s father, to family portraits, to photo negatives and ink drawings.

Nevertheless, after submitting the exhibit to ninety different museums, all Harithas had for his troubles was a file folder full of rejection slips. The San Jose Museum of Art had turned him down because some of the exhibit’s work was “too polemical and might offend our audience.” Two Westchester County legislators in New York issued a statement demanding that the County Executive prevent even a fundraiser for the exhibit from taking place. The statement accuses the exhibit of containing “several paintings, photos, and poems that demonstrate anti-American, anti-Israel, and anti-Jewish hatred.”

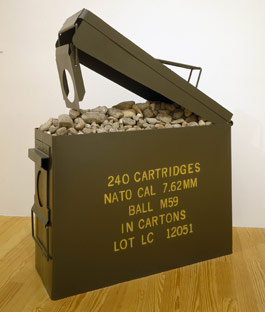

Adding to the various critiques of the exhibit, New York Assemblyman Ryan Karben protested the “displays of violence that the artists claim are showing the proud Arab masses standing up to advanced ammunition of the Israelis using only stones.” The offending piece of art? An ammunition box that would normally hold bullets for M-16 rifles filled with rocks. And the artist never even made the claim that Karben attributed to him. According to the exhibit catalogue, the box in question was intended by the artist to communicate the “commentary on unfair fighting.”

Finally, after two years of searching, the exhibit finally found a venue in San Francisco—in a small cultural center downtown. One of the few artists who could leave Gaza and the West Bank to attend the opening was Vera Tamari. An art teacher in Ramallah, Tamari seemed like the perfect person to provide insight into the Palestinian art movement. When I asked her what she intended to convey with her artwork—largely consisting of ceramics and relief work—she said very little about politics. Rather, she explained, her focus was simply to make the concept of “Palestinians” and “Palestine” visible to the public:

I think it’s an important reflection that there is a people and that the people have a right to express themselves. They have issues that they want to tell the world, stories that they have to tell the world. Many of the works here are not directly political, but they are political in the sense that we want to tell the story of what’s happening in Palestine. People ignore the fact that there are Palestinians who have the same potential as other people in the world, that Palestinians are like other people, that they can live, can produce art and music. [Read more here.]

“Father,” by Tyseer Barakat. View a larger version

Even as I pushed her to explain the underlying political message of her art, Tamari kept pushing back to make the point that Palestinians were a real people and that the highest function of the art was to reveal that these people exist and have a culture. That simple statement was her politics. The fact that this reality is often obscured lies at the root of our inability to have a proper discussion about Palestine. In 1969, then-Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir told London’s Sunday Times, “There is no such thing as a Palestinian people… It is not as if we came and threw them out and took their country. They didn’t exist.” Early Zionists coined the slogan, “A land without a people for a people without a land.” Since then, Palestinians have struggled to assert that they do, in fact, exist; not just as martyrs and militants with a political agenda, but as a people with a culture that many would like to erase.

Even today, Harithas struggles to find American museums that will house the exhibit. It is possible that three more U.S. exhibits will come about; two of which will need to be funded with money the Palestinian artists have raised themselves, and one by a university. Meanwhile, the Mexican government has tentatively agreed to fund an exhibition in Mexico City, and there are rumors that it may find a venue in Australia. Harithas would like to see the sort of discussions he saw in Houston, open discussions about Israel and Palestine, take place in other U.S. cities. But it’s not clear that this will happen anytime soon.