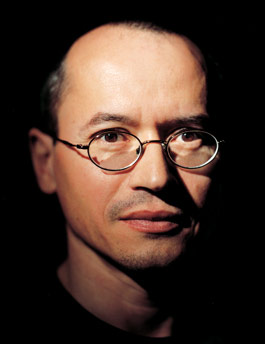

Photo: Lars Topelmann

Joe Sacco occupies a unique spot in the no-man’s-land between underground cartoonists and war correspondents. By presenting his firsthand reporting from hot spots like Gaza, Sarajevo, and Iraq in gritty black-and-white comics, Sacco has won over serious fans of comics and nonfiction alike (and has been name-dropped on The O.C., of all places). His first graphic novel, Palestine, chronicled his travels in Israel and the West Bank during the first Intifada. That was followed by the widely acclaimed Safe Area Gorazde, which depicted his experiences holed up in a besieged Bosnian Muslim enclave. Sacco’s work is often called “comic journalism,” but that label doesn’t fully capture how he’s managed to simultaneously blend and defy both genres. It’s not your typical journalist, after all, who seeks inspiration from Robert Crumb. And it’s not your typical comic-book artist who goes looking for wanted war criminals like Radovan Karadzic, as Sacco does in his latest collection, War’s End, published in June.

The 44-year-old Sacco came to cartooning after a series of what he calls “half-assed” reporting jobs, but he isn’t after scoops: He looks for stories that will resonate long after the shooting has stopped and the ink on other reporters’ stories has dried. He took a break from the drawing board to speak with Mother Jones from his home in Portland, Oregon.

Mother Jones: How did you start doing this combination of reporting and cartooning?

Joe Sacco: I was already doing comics. Perhaps the first quasi-journalistic thing I did was go on tour with a rock band in Europe and write about those experiences. Almost all of it is true—I was writing down everything they were saying. When I went to Palestine I thought I’d do an autobiographical account, and it turned into something more journalistic. When I was there, something clicked in my head; I found myself interviewing people, searching out facts and figures. Later on I became much more self-conscious of what I was doing. When I went to Bosnia, I was there to tell someone else’s story and I was more methodical.

MJ: When you’re out doing interviews, are you looking at people as an artist and sketching them at the same time?

JS: I tend to wear the hat of reporter more when I’m interviewing people. I’ll tape-record or take notes. I always ask a subject if I can take his or her picture. In about 90 percent of cases they’ll say yes, but when they say no, I’ll surreptitiously do a quick drawing. It won’t be such an exact likeness that they could be identified.

MJ: Do most of the people you talk to getit when you tell them that you’re a reporter but you’re going to work them into a graphic novel?

JS: My guide had a copy of Palestine on my last trip to Gaza. He’d bring it out and show people what I was trying to do. That usually went over pretty well. Because there were actually drawings I had made of Gaza before, they were able to look at it and say, “Oh, this is me, this is much like the refugee camp I’m living in.”

MJ: When you’re re-creating events you haven’t witnessed, do people ever challenge your portrayal of those scenes?

JS: I try to ask visual questions. I’ll ask what someone was wearing, if that seems relevant. If possible, I’ll walk over the same ground that they’re depicting. Of course, I can never get it precisely as it was. It’s like a film director trying to represent a scene that took place in the 1700s. You reconstruct it to the best of your ability.

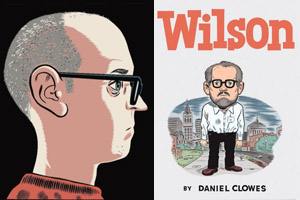

MJ: You’re usually the most cartoony character in your stories—your glasses are blank, your facial features exaggerated, your limbs rubbery. Why depict yourself like that?

JS: When I started Palestine it was a bit rubbery and cartoony at the beginning, because that’s the only way I knew how to draw. It became clear to me that I had to push it toward a more representational way of drawing. I tried to draw people more realistically, but the figure I neglected to update was myself.

MJ: War’s End is your third book set in Bosnia. Why have you kept coming back to that experience?

JS: I think any journalist who spends time in a place realizes that there are lots of stories around beyond their primary story. You meet so many interesting people and have all kinds of experiences. There’s probably one more story about Bosnia that I’d like to do, because I spent a fair amount of time on the Serb side of the lines, which isn’t apparent in the other books.

MJ: In the story “Christmas With Karadzic” in War’s End, you are trying to track down Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic, who was wanted for leading the slaughter of thousands of Muslims and Croats, but when you find him, you have a very different reaction than you expected.

JS: I’d been stewing about Karadzic for a long time. Sometimes when you’re a journalist you put aside your personal feelings about someone because it’s more important to get the story. Then when you finally meet them, you’re not prepared. I realized I had nothing to say to this man. What could I say? “How could you do this?” That story is really about the fight between being a journalist and being someone who actually cares about what they write about. Maybe if he had strutted in or if there was some huge convoy and hundreds of paramilitary men around him, I would have been awed and hateful in the way I expected. He didn’t seem that intimidating.

MJ: That story is an interesting contrast to the story “Soba,” in which ordinary Bosnians come across as much more alive and interesting than someone like Karadzic.

JS: I think a journalist always connects better with the people around her or him than with a general or a politician. Those people are built to spin—that’s what they do. I will interview bigwigs if I get the chance, but you are seldom surprised by people in power—you’ve got to get awfully damn close to get anything new. I’d much rather hang out in a café. That’s where things are really happening.

MJ: Is becoming a conflict junkie an occupational hazard?

JS: I think it’s inevitable with anyone who’s covering these kinds of things—it’s interesting and on some level it’s just an adrenaline rush. Of course, I’m drawn to a place like Iraq because it’s the biggest story of our generation.

MJ: Are there any journalists or artists you look to as models?

JS: The people whose work I’ve admired are people like George Orwell and others like Michael Herr and, of course, some of Hunter S. Thompson’s work. I like good, straight reporting, too. Robert Crumb is an influence on how I draw, but not on the subject matter I take or my approach. One thing I do like about Crumb is that he’s chronicled his age, his times, and I think that is what artists should do.

MJ: As more cartoonists do reporting, what is the future of comic journalism?

JS: More editors seem to be aware of how comics can be melded with journalism and are interested in experimenting with the form. That’s good for cartoonists, but the work has to be good. In the end, we’re going to stop getting a pass just because we’re cartoonists. At some point someone is going to say, “How does this stack up against good prose journalism or documentaries?”

MJ: Do you think there’s any advantage to this kind of storytelling?

JS: It’s a visual world and people respond to visuals. With comics you can put interesting and solid information in a format that’s pretty palatable. For me, one advantage of comic journalism is that I can depict the past, which is hard to do if you’re a photographer or filmmaker. History can make you realize that the present is just one layer of a story. What seems to be the immediate and vital story now will one day be another layer in this geology of bummers.