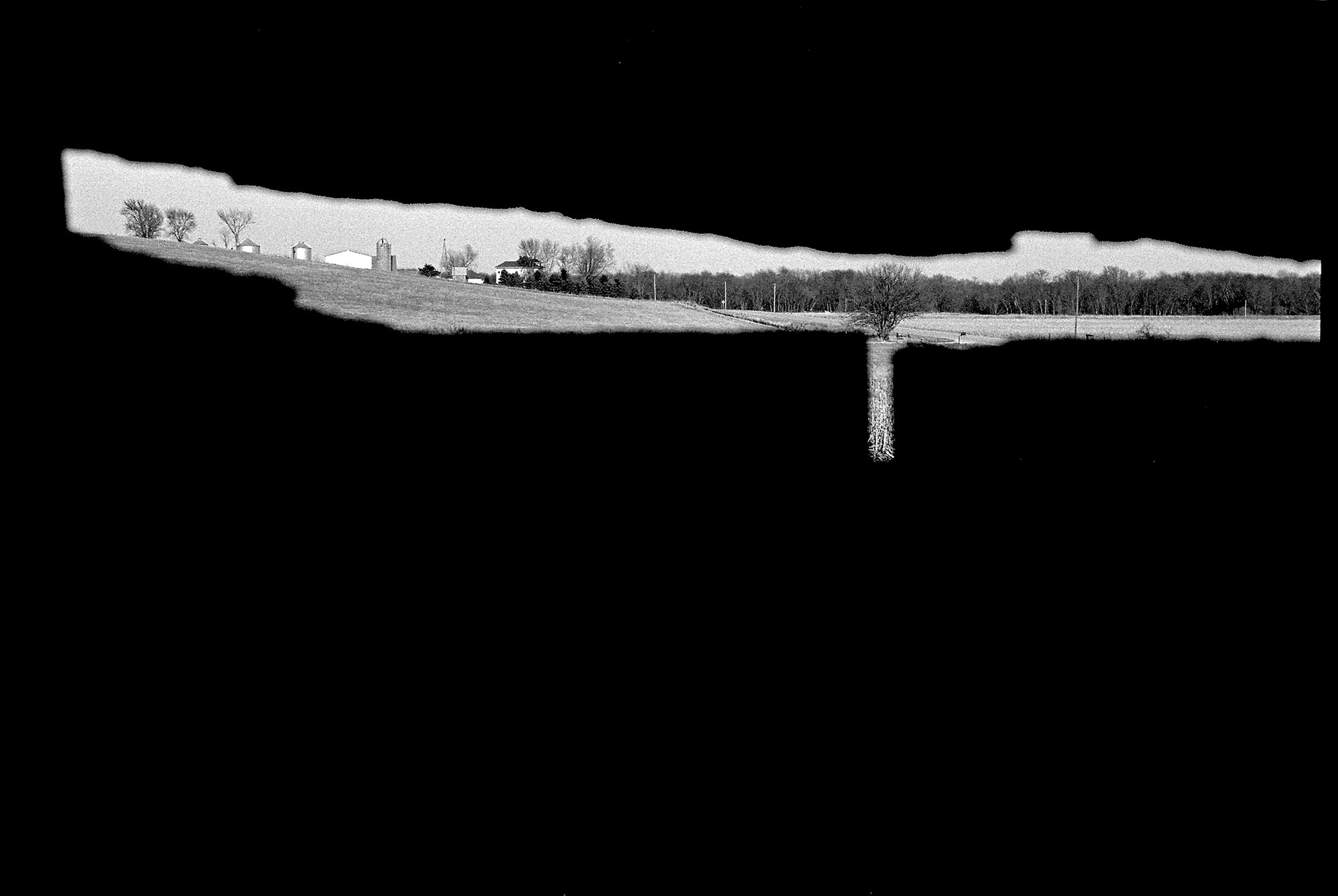

On either side of old Highway 218 in far southeastern Iowa, rows of corn are broken to stubble and furrows are filled with ice. It’s late December, just days to the caucuses, and the wind knifes across the prairie, so bitter cold that even red-tailed hawks, feathers fluffed for warmth, hunker atop speed limit signs. Granted, much of what you see here is what you’d expect: each town with its water tower and circumscribed cemetery, each small farm with its Harvestore silos and propane tanks huddled under leaf-bare oaks. These are the cliches of the Midwest and the Great Plains—what folks on the coasts call “the heartland” when they’re feeling generous, “flyover country” when they’re not—and like all cliches, there’s some truth to them.

Iowa is still dominated by the descendants of white European immigrants who showed up here in the 19th century and have farmed this land ever since. The state, however, is anything but a quaint picture postcard, and when presidential hopefuls descend every four years, glad-handing their way through a string of pancake breakfasts and highway diners with the national media in tow, they risk the ire of the very people they are trying to woo. And some pay the political price. Just ask Mitt Romney.

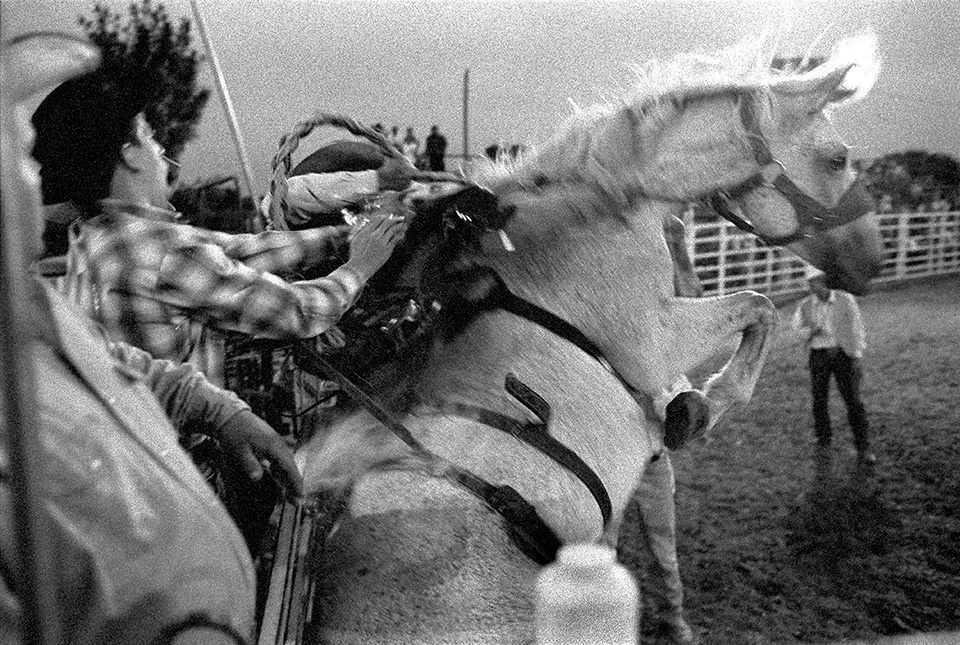

So be warned: Iowans are a tough lot, and they brook no bullshit. The stereotype of the laconic, weather-beaten Hawkeye isn’t far from the truth. But spend even a little time here, and you’ll see why.

From Driftless, published by Duke University Press.

Listen to the photographer introduce himself and his work:

Several years ago, when my wife was pregnant with our son, we went prowling the antique stores of Riverside, just off this same highway, in search of knickknacks to decorate our nursery back in Iowa City. My wife fell in love with a wooden, handmade barn with a hinged roof that opened to reveal perfectly rowed stalls. When I lugged it to the counter, the woman who ran the store told me that the toy maker was a local man and would be pleased that we had chosen this item. His arm had been ripped off at the shoulder in a farming accident only a few years before, and he now passed his time making replicas of the farm he could no longer work. She didn’t say it to be shocking or to elicit my sympathy; it was just the way things were, and she was bringing me up to speed.

This is what photographer Danny Wilcox Frazier means when he says, “Life in Iowa can be punishing.” Your livelihood and way of living, your very place on this earth, are in doubt every minute, every day, and generations have grown up with the unspoken understanding that even when you do everything right, everything exactly as you were told, things can still go wrong–too dry and corn can be lost to drought, too wet and soybeans succumb to downy mildew; sudden blizzards can literally snow cattle under, but muggy weather can spread pseudorabies through hogs.

“Many Iowans,” Frazier says, “endure the hardships associated with a life inextricably bound to the ups and downs of nature.” And he should know; he’s a lifelong Iowan who, after a few years abroad, made the hard choice to come back, to stay.

There are fewer and fewer like him. With each successive census, the number of college-educated Iowans declines—not because of a drop-off in the quality of the state universities and community colleges (enrollment, indeed, is growing), but because there are too few jobs to sustain college-educated workers in rural parts of the state. Especially hard-hit are towns in the immediate orbit of larger urban and cultural centers like Iowa City.

Listen to the photographer talk about his desire to escape:

The places Frazier has photographed—small towns that straddle either side of 218, like Coppock, Conesville, Kalona, Riverside, Hills, and North Liberty—are daily disappearing, casualties of a generational and economic divide that separates rural and urban classes.

Listen to the photographer talk about this photo:

“Rural America,” Iowa native Ted Kooser has written, “is peopled to a great degree by introverts and is their haven. If an extrovert is born to the family of one of my neighbors, that child is certain to leave our community upon reaching maturity, packing his or her garrulousness, making a point of saying good-bye at least twice to everybody in reach and leaving the rest of us all the more quiet and, frankly, comfortable.” Kooser offers this wisdom with a smile and wink, but there’s a lot of truth to what he says. The prairie has always been populated by loners, recluses, and outright hermits.

Hamlin Garland, when his family arrived in Iowa in the 1860s, marveled that his father “was in his element. He loved this shelterless sweep of prairie.” To survive here, you have to have that gift for living inside of silences, for finding calm within your mind when there’s nothing from the outside to feed it. But even in these days when small towns enjoy satellite dishes and cell phones galore, all the technology in the world still can’t change the fact of physical distance.

Most parts of Iowa are still an hour’s drive or more—when the weather is cooperating—from what most urbanites would consider civilization. Call it what you like. Brain drain. Rural flight. Either way, young people who grew up in the country, especially the best educated and most ambitious, are packing their garrulousness and never coming back. What is lost is not only the hope and vitality that a new generation brings but also that essential connection between the history of a place and its physical spaces.

Listen to the photographer talk about growing up in Iowa:

Listen to the photographer talk about this photo:

Whole towns are turning into abandoned farmhouses and rusting hay rakes, becoming those unkempt country churchyards where nobody stops to decorate graves and no one recognizes the names of the dead. Soon, these towns will disappear off maps, fade from the pages of old books. Soon, a few photographs—a few exquisite images captured on film—will be all that remain to remind us that they ever existed.

Listen to the photographer talk about this photo:

Little wonder, then, that a majority of Iowa caucusgoers told pollsters they were seeking candidates who promised a change from the status quo. Maybe Iowans, more than anyone, feel this need and, better than anyone, recognize that the face of change won’t necessarily be white.

For all the punditry about lily-white Iowa, the survival of its small towns is increasingly dependent on Mexican and other Latin American immigrants. A town like West Liberty, just southeast of Iowa City, is now more than 40 percent Hispanic—many drawn by the railroad in the 1920s and now by West Liberty Foods, a meat-processing plant that slaughters more than 20,000 turkeys per day. The effect is unmistakable; on downtown 3rd Street, for example, pizza joints with names like Paul Revere’s and Hawkeye Pizza sit cheek by jowl with Mexican places like Buelitos and La Mexicana.

American Legion Post 509 is next door to Acapulco Mexican Bakery, and the local paper sometimes runs stories in Spanish. That newfound diversity may not always sit easy—some in neighboring towns derisively call it “Wet Liberty”—but these small towns will do what they always do: whatever it takes to survive.

Listen to the photographer talk about this photo:

Listen to the photographer talk about this photo:

For now, the sun is sinking as my car nears Iowa City, and the whole of the state is socked in fog. I know the town of Hills sits just east of the highway, and I can’t help but think of Frazier’s stunning photograph of a lone farmhouse, locked in snowy silence, the only sign of life the smoke spiriting from the chimney and the barn light casting long shadows across the field. But tonight, even the faint lights of Hills flickering to life are nothing more than ghosts in the mist.

As I turn off old 218 onto Interstate 80, the fog thickens and spreads, and the traffic turns into an eerie procession of red taillights, haloed in the haze. I speed west across the black expanse toward Des Moines, all sign of these little towns receding into the dark distance.

Listen to the photographer talk about this photo: