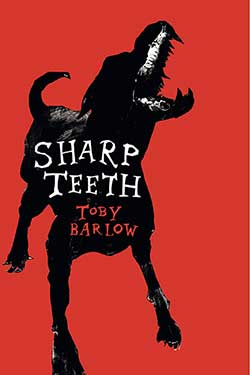

In his debut novel, Sharp Teeth, Toby Barlow introduces us to a Los Angeles filled with werewolves who don’t need a full moon to go from human to lycanthrope. They’re everyday people, leading normal lives right under our noses, but that they can switch to animal form at will, and even become pets for lonely housewives when the heat is on. These werewolves are pack animals. Alone they are vulnerable, together they are strong, and they are bent on fighting other packs to take over the City of Angels.

There’s more to Sharp Teeth than fantasy and horror. There’s the love story of a dogcatcher who ends up in a relationship with a woman who is more than she appears. There’s homage to Bukowski and Chandler as well as poets of millennia past. And to completely tweak us out, Barlow’s written his five-part tale entirely in free verse. Reading the first 10 pages is a bit jarring, but once the rhythm kicks in, Sharp Teeth is hard to put down. It’s completely engaging on every level, with sympathetic characters and a driving plot that grabs you by the throat like a pit bull and doesn’t let go until page 308.

Barlow has broken the rules of conventional novel writing, gaining a readership that continues to grow by word of mouth. Sharp Teeth is a future cult classic that will continue to be discovered by readers hungry for sex, violence, and a fantasy world wrapped up in a literary work. Its sudden success has caught Barlow, whose day job is as a creative director of an ad agency, somewhat by surprise. A decade ago, when he was going through a rough patch, a psychic offered an unsolicited look into his future and told him to wait until he was 42 years old. On the day of his 42nd birthday, he kicked off his book tour and the LA Weekly gave Sharp Teeth a stellar review. Nick Hornby has also praised the book, saying, “Sharp Teeth will end up being clasped to the collective bosom of the young, dark, and fucked-up.” Barlow spoke to Mother Jones from Minneapolis.

Mother Jones: I have this weird thing about dogs now. The next time a dog humps my leg, I think I’m going to have sexual thoughts because of your book.

Toby Barlow: I was just going on a walk around a lake here in Minneapolis, and I find myself making eye contact with all the dogs in a slightly deeper fashion than I used to.

MJ: So writing the book changed your relationship with dogs as well.

TB: Yes, in a pretty scary manner. I was always sort of a dog person. I had pets growing up and stuff, but when you write a whole novel about them, you become a part of their community.

MJ: Let me ask you about the parallels between dog and human relationships. I was craving some of the intimacy the dogs had in the book, the sense of belonging to the pack.

TB: I think human beings have all these tools for social connection, which should bring us together but instead causes all sorts of confusion and discombobulation. With dogs, they’re either fighting or they’re falling asleep on one another’s necks. It’s a much simpler form of community that they’ve come up with. I agree, people are oftentimes very self-congratulatory about the civilization we’ve built around us, when in fact lying at our feet are much simpler and more satisfied societies.

MJ: The book brings to light that there’s so much we can learn from dogs to become better humans.

TB: It’s funny; there’s a parallel book that just came out by a woman who retrained injured dogs. She decided to try the same elements on her boyfriend to teach him how to be a good boyfriend. That’s one simplistic example, but I think to a great degree there is a loyalty and there is a bond between dogs that we have a hard time coming to terms with. And I think that dogs accept that they can live together and not understand one another, and I think that we somehow always try to have a complete and transparent understanding of one another, which just leads to more confusion.

MJ: The story seems like it could also be a reflection of America and corporate America. This is especially true of the character Lark, who heads a pack of wolves and maintains businessman sensibilities when it comes to how the pack works and how they make money. The book plainly hints at the possibility that they’re corporate assassins.

TB: Yeah, I definitely try to play with the themes of class and the idea of how packs operate, and Lark’s pack is definitely a very corporate pack: You’re either in the pack or you’re out of the pack. Lark’s pack is very unconcerned with the rest of the world, for good or for ill. I think when Aristotle said that man is a political animal, he was really saying that man is a pack animal. We’re social beasts, and we draw society around us. I think that there’s a brutality of behavior to anything that’s outside the pack. I remember when the Florida recount was going on and I was sitting on the porch with a few people in Philadelphia and someone said, “Bush is going to be elected and a few people are going to make a lot of money.” And that’s when you realized the Republican Party had changed, and it wasn’t just about all the rich getting richer; it was actually a much smaller pack. It was the Cheney/Bush pack. It’s ironic that they use the word PAC [political action committee] to describe fundraising. There are a lot of truths to the brutal and inclusive way these different groups operate.

MJ: The book’s free verse forced a rhythm and gave it a romantic connotation right away. I don’t know if that’s what you were aiming at.

TB: I was aiming at a mood. I wanted it to be a little dark and a little strange and a little bit driving, and I don’t think people are used to reading verse as a tool for a driving narrative, but I found that it really helped that way. So that, to me, was the “Aha!” discovery of the book: If you use fewer words, which is what verse does, you can speed things along in a really propelling fashion. That was the biggest surprise. On a couple of blogs I’ve seen, people have talked about it as gimmicky. I was talking to a friend yesterday—I work in advertising and he works in advertising—and he said, “You know, if you came to us and said that you wanted to publish a book and sell a lot of copies, as advertising and marketing professionals we would probably suggest that you not use a format that went out of fashion a thousand years before Christ died.” So the idea that this is some kind of marketing ploy is entirely laughable as far as I’m concerned. But at the end of the day, it was the voice that I found to tell the story. A pared-down language that resembles poetry and resembles good rock lyrics and a lot of forms of language. But it was just fun to play with.

People really spend a lot of time reading verse and they don’t even realize they are. When they’re looking up lyrics to their favorite Jay-Z songs, people read a lot more poetry than they actually give themselves credit for.

MJ: I love Venable’s description of Los Angeles on page 175:

This is a violent city

and I don’t mean rapes and bloodshed.

I mean the existence of every ounce of it.

This entire vast urbanity was bludgeoned from the earth,

torn and wrought,

piece by piece. A thousand bricks.

TB: That’s sort of an underlined theme of the whole book, which I kind of make overt there, which is basically just an extension of the Walter Benjamin quote at the beginning: We’d like to think it’s all kind of clean and easy, and it’s not. Every ounce of every civilization we have is this violently wrought thing. Everyone’s just all, “Oh, I live in Santa Monica, but I’ll recycle my aluminum and I’ll be clean, I’ll drive a Prius and be guiltless.” But the whole infrastructure you’re sitting on is fundamentally false.

MJ: Anyone who has read the book is going to want the answer to this question. Have you sold the film rights?

TB: Yes, I have. People are working on screenplays. This is the first poem about pets to be optioned since T.S. Elliot sold Cats.

MJ: I think if they cast this right and they get the right director, this is going to be bigger than Fight Club.

TB: I don’t know if anybody out there can do it; that’s the tricky part. I don’t think there’s a director out there who can bring it to life. I like that people see it in a cinematic way, and I think in literature people sometimes consider that a negative, but I consider it a positive because I feel like I’m competing with movies. I’m competing with television shows. So for it to feel as alive and as fun as watching it as a movie or watching it as a television show, for me that’s a great success. It means that I successfully conjured up visions in people’s heads, which is why literature was invented in the first place. The coolest thing is when I’ve been out on readings and teenagers come up to me and are excited and say they just read it and it was really fun. Getting people to pay attention to books is a difficult thing, and to get a teenager to pay attention to a book today is an enormous challenge. You’re up against Halo and you’re up against Wii and you’re up against PlayStation and the Internet.

One of the reasons I like George Plimpton is because he got all the boys to read Paper Lion, and so many guys who are journalists now are like, “I read Paper Lion when I was a kid; it changed my life.” I think that’s the hardest audience to hold on to. So if you can make a guy read a book and feel like that he’s not a total nerd, you’ve succeeded. If I can keep getting teenagers to read this book, I would have more satisfaction out of that than if it was made into a movie.

MJ: Is there anything we haven’t discussed that you’d like to talk about?

TB: One thing I’ve been thinking about recently was that I was raised a Quaker and I went to Quaker summer camp and Quaker schools, and some people are going, “That’s kind of weird that a Quaker would go and write an ultraviolent book.” And I was raised under the philosophy of tough Quakerism and that it takes a lot of strength and a lot of understanding of violence to be a pacifist. So to me it made a lot of sense.

MJ: Are other Quakers frowning on your being a practicing Quaker and writing an ultraviolent book?

TB: You know, it’s a very forgiving religion. The Quakers I know, their reaction to the book has been very positive, but only sort of anecdotal, like, “Oh cool, you wrote a book.” Receiving the book in the spirit that it’s intended. I don’t think that it’s in any way promoting violence. I think it’s sort of acknowledging that we are animals, and if we choose to be violent, then what we’re choosing to do is embrace our more animal spirit. And if we don’t want to be violent, then we’re going to have to figure out ways to get beyond that.