Photo: Mark Murrmann

Read the extended version of this interview here.

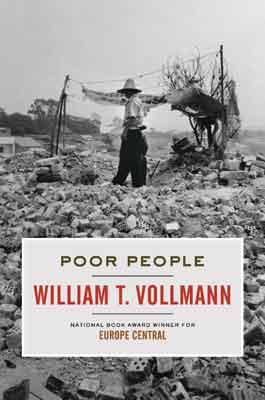

William T. Vollmann contains multitudes. Over the course of his career, the insanely prodigious 49-year-old author has cranked out nearly 20 works of fiction and nonfiction on themes ranging from Native American history to World War II to his experiences hopping freight trains, befriending prostitutes, and smoking crack. He’s traveled the world seeking out extremity; he’s nearly frozen to death in the Arctic and survived hitting a land mine in Bosnia. And he’s not afraid to go long: Several of his books are massive, most notably Rising Up and Rising Down, a seven-volume, 3,300-page exegesis on the morality of violence. While Vollmann has earned critical acclaim and the odd mention as a future Nobel laureate, he may be America’s best-known unread author. On a recent afternoon, Vollmann sat down in his studio, a former Mexican restaurant in Sacramento, California, to sip scotch and talk about the irrelevance of popularity, his distrust of the Internet, and his latest work, the 1,300-page nonfiction epic Imperial.

Mother Jones: Imperial isn’t just about California’s Imperial Valley, but a place called Imperial, which you describe as “the continuum between Mexico and America.”

William T. Vollmann: I decided that there is really some sort of entity that I call Imperial, and I decided to extend it all the way along the California-Mexico border and into Tijuana and then to the Pacific because it all has a similar feeling. We’re living in what used to be Mexico, and there’s this very fluid border feeling. There are parts of L.A. that feel very, very Mexican, and there are weird little enclaves of Northside in Mexico—Cancún for instance. So what is a border?

MJ: Talk about the terms “Northside” and “Southside,” which you use in the book.

WV: Those are border patrol terms. I never heard anyone who wasn’t in the border patrol use them, but I think they’re perfect.

MJ: You write that Imperial was originally going to be a piece of fiction, and then you decided that wasn’t the right way to go.

WV: At least for me, it takes more knowledge to write fiction than nonfiction. You could imagine writing about a prostitute, for instance, but if you haven’t spent time with prostitutes then you’re going to get all these details wrong. But if you have a lot of sex with prostitutes and you’re friends with prostitutes and you interview prostitutes, then maybe after many, many years you might be able to create prostitute characters. I feel like I’m almost ready to write fiction about the border. But even after 10 years of writing nonfiction about it, I don’t think I know quite enough to do it right.

MJ: Does that make you question the fiction you wrote when you were younger?

WV: No, I don’t think so. I think—at least I hope—that the fiction I’ve written so far has flaws but has mostly been successful. Hemingway always said, “Write about what you know.” I think that we’re all, as human beings, so limited. If we want to write about ourselves, that’s fairly easy. But if we want to project ourselves somewhere beyond our personal experience we’re going to fail. When I go train hopping and I look up into the sky, there are always so many more stars than I remember there were.

MJ: Prostitution’s been a big theme in your work. Have your attitudes toward or your relationships with prostitutes changed?

WV: Well, I’m getting older, so I can’t get it up as much as I used to. I think prostitutes are amazing people with so much knowledge of human nature and so many fantastic stories. Some of them are scam artists, but most of them are very, very brave and a lot of them compassionate. I think it should be legalized.

MJ: In one chapter of Imperial, you use a hidden camera to investigate maquiladoras.

WV: Homeland Security wasn’t too happy about that. As a result of that one I was detained for about seven hours. They called the FBI. Idiots.

MJ: How many times did you get detained at the border?

WV: Oh, three or four.

MJ: You’ve described yourself as a member of the “Society of Fat Books.” Do you ever worry that with every additional page you write you’re diminishing the number of potential readers?

WV: Everything has a life. We all have lives and everything comes to an end. So I don’t think that we should be concerned with making everything we create more popular. There will come a time when nobody reads my books and no one remembers who I was. In the meantime, I’ll do it my way.

MJ: How do you know whether a book will be short or long?

WV: It’s just as long as it needs to be. With Rising Up and Rising Down, I didn’t know that it would take me 23 years.

MJ: You don’t do much online. Why not?

WV: Well, there isn’t really any good Al Qaeda child porn.

MJ: I think you just added three hours to your next border trip.

WV: You know, I have a couple issues with the Internet. One is the fact that you get spied on. That sort of pisses me off. But I guess what really creeps me out is the mutability of the so-called information. It would be so nice if, say, the Library of Congress made archival hard copies of the Internet each day. Because then you would have copies of something you could trust 100 years from now.

MJ: Do you think your works will have a future in a digital form?

WV: Sure. Why not? But I’d be happy if they had a paper future as well. I have some people living in my parking lot, and they don’t have laptops. Sometimes I see them reading. A book is such a great piece of technology in that regard. You don’t need batteries. You don’t need anything but daylight.

MJ: And time.

WV: I think we’re all going to have a lot more time. The US is losing its economic clout. There are going to be fewer jobs. We’re all going to be idler. So hopefully instead of spending all of that time looking for nonexistent jobs, we’ll have more time to talk about the future and the past. It won’t be all bad, you know?