DAN RATHER IS EBULLIENT, more so than usual, as we hurtle north from San Diego in a rented Chevy SUV. The former CBS News anchorman is recounting a story he’d reported in 2007 about problems with electronic voting machines. “We found out that these wonderful, electronic, technological marvels were manufactured in what amounted to a sweatshop in the Philippines—the Philippines, exclamation point!” he says, in that ascending tone so familiar to generations of Americans. “The equipment wouldn’t fit in its boxes, so the workers, two of them, had to put their feet on the thing and shove it into the box. They’ve got to get it in there, it’s got to ship, and so they’ve got four feet in there pushing this thing.” He lets out a laugh. “In some cases, the company’s explanation of why these things are good fell into the category of ‘If bullshit were music, these guys would be a full symphony orchestra.'”

The recollection has gotten Rather, who is clad in his familiar anchorman’s attire, visibly fired up. He phones his executive producer back in New York, saying he wants to revisit the story. He then cranes around to the backseat and asks his young assistant to track down the author of a recent book on voting machines. As we come to a stop on a hilltop overlooking the city, Rather flips open his notebook, glances over his questions, and swings himself out of the car, ready for his interview.

Rather is 79, with thinning gray hair and more wrinkles than in his CBS days. Two streamlined hearing aids hang over the backs of his ears. But he hasn’t let age slow him down. He’s come here to cover developments in the Catholic priest abuse scandal for Dan Rather Reports, which airs on a tiny independent cable channel called HDNet. His show is a throwback to the comprehensive reporting that was commonplace on television when he launched his career more than half a century ago. Rather and his crew tackle meaty, challenging stories (environmental degradation in Africa, banks that help Iran launder money), often devoting the full hour to a single topic—the show won an Emmy for cinematography in 2008 and another one last year for business reporting. Rather appears as enthusiastic about his work for this obscure outlet as any that he has done in his lengthy, storied career. “Dan Rather is living a dream today,” says Joe Peyronnin, a former CBS News exec who worked with Rather for 14 years and served as president of Fox News during its launch. “He is doing what he wants, and he can cover any story.”

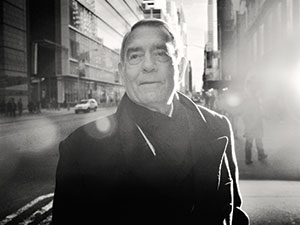

Dan Rather near his office in New York City. Christopher Anderson/NaMagnumThat may all be true, but Rather had expected to end his career at CBS. He’s only at HDNet because CBS jettisoned him following the scandal over his exposé on former President George W. Bush’s Air National Guard service. Mark Cuban, HDNet’s owner, loved Rather’s polarizing image and believed such a huge brand could bring attention to his tiny shop. He lured the anchor to this obscure end of the channel guide by offering him total creative control. Neither Cuban nor his executives vet story ideas or scripts. Cuban just writes the checks and watches Rather’s show when it airs.

Dan Rather near his office in New York City. Christopher Anderson/NaMagnumThat may all be true, but Rather had expected to end his career at CBS. He’s only at HDNet because CBS jettisoned him following the scandal over his exposé on former President George W. Bush’s Air National Guard service. Mark Cuban, HDNet’s owner, loved Rather’s polarizing image and believed such a huge brand could bring attention to his tiny shop. He lured the anchor to this obscure end of the channel guide by offering him total creative control. Neither Cuban nor his executives vet story ideas or scripts. Cuban just writes the checks and watches Rather’s show when it airs.

This independence comes at a price, however. During his 44 years with CBS News, Rather became perhaps the nation’s best-known newsman, reaching 18 million viewers a night at his peak. HDNet is only available in about 20 million households—top 25 outlets like USA or the Discovery Channel boast more than 100 million. And since Cuban won’t pay for Nielsen ratings, Rather has little idea how many people are watching. HDNet’s mainstays are mixed martial arts, pro wrestling, a travel show hosted by women in bikinis, and Girls Gone Wild Presents: Search for the Hottest Girl in America.

MARK CUBAN’S OFFICE in the basement of the American Airlines Center—the Dallas arena that’s home to his NBA team, the Mavericks—feels like a VIP room at a not-particularly glamorous nightclub. Four TVs surround a giant projection screen on one wall. Half a dozen club chairs are arranged around a coffee table the size of a double bed. There’s a bar off to one side. The traditional office part is almost an afterthought, a desk relegated to a glassed-in corner and cluttered with boxes of Mavericks bobblehead dolls.

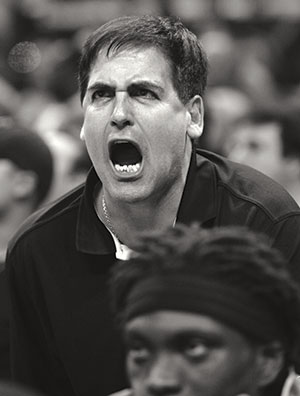

The billionaire sits in one of the club chairs, feet on the table, watching CNBC on the quartet of TVs at a punishing volume. Tanned and muscular, dressed in a T-shirt and jeans, he looks much younger than 52. Cuban, who is notorious for his courtside antics and the $1.8 million in fines he’s racked up from the NBA, leans forward and grins anytime he senses a disagreement coming on. Argument, debate, contrarianism are his preferred states. The last time he worked for someone else, back in the early 1980s, he got fired. Cuban has never been employee material.

Mark Cuban courtside at a Mavericks game. Erich Schlegel/Dallas Morning News/CorbisHe grew up in a middle-class Pittsburgh suburb, where he sold trash bags door to door at age 12, and later earned $25 an hour teaching disco moves at a sorority house. During college at Indiana University, he opened a bar, and upon graduating he followed his school buddies in pursuit of “fun, sun, money, and women” to Dallas, where he taught himself to write code. In 1990, Cuban sold his first real business play, a computer consulting firm, for $6 million. He also launched and sold a hedge fund and relocated to Los Angeles, where, with less success, he tried his hand at acting. (Some recent cameos on HBO’s Entourage compelled the Wall Street Journal to jeer that Mark Cuban wasn’t even believable as Mark Cuban.)

Mark Cuban courtside at a Mavericks game. Erich Schlegel/Dallas Morning News/CorbisHe grew up in a middle-class Pittsburgh suburb, where he sold trash bags door to door at age 12, and later earned $25 an hour teaching disco moves at a sorority house. During college at Indiana University, he opened a bar, and upon graduating he followed his school buddies in pursuit of “fun, sun, money, and women” to Dallas, where he taught himself to write code. In 1990, Cuban sold his first real business play, a computer consulting firm, for $6 million. He also launched and sold a hedge fund and relocated to Los Angeles, where, with less success, he tried his hand at acting. (Some recent cameos on HBO’s Entourage compelled the Wall Street Journal to jeer that Mark Cuban wasn’t even believable as Mark Cuban.)

In 1995, Cuban and his friend Todd Wagner launched Broadcast.com, which put audio and video of sports online. Four years later, at the height of dot-com mania, they sold it to Yahoo for $5.7 billion in stock—Cuban pocketed more than $1 billion. “I am the luckiest motherfucker in the world,” he says. “It’s like I tell people, ‘When I die, I want to come back as me.'”

In 2001, he and Wagner launched HDNet, the first high-definition channel. They were betting that high-def TV sets would take off, and they have; half of American households now own one. But therein lies the problem: While Cuban was once the sole purveyor of high-def programming, everybody’s doing it now. Absent the format advantage, it’s not clear what HDNet’s organizing principle is. Cuban makes the programming decisions personally, based as much on his own interests as on any business concern. “Our content is born of an independent mind—Mark Cuban’s mind,” says Philip Garvin, a third cofounder who serves as chief operating officer.

Cuban isn’t chasing after advertisers; HDNet makes most of its money from subscriber fees paid by cable and satellite content distributors. His model is to appeal to strong niches like fight fans or Girls Gone Wild watchers. But beyond its boobs-and-brawl content, the channel has always supported investigative reporting. “Mark believes in journalism and true First Amendment rights,” says Wagner. “He is not afraid to tackle issues that some don’t agree with.” Not long after the channel launched, Cuban began airing the newsmagazine World Report, which won an Emmy last year for a story on human trafficking in South Africa. “We have great freedom to do the work that we feel needs to be done,” says Dennis O’Brien, the show’s executive producer. “It’s a wonderful place to be a journalist.”

Cuban is also behind Sharesleuth, a website that digs up dirt on companies, and which he funds by shorting the stock of said companies—a model that flies in the face of traditional journalistic ethics. The business press is dying, Cuban explains, and this is one way it might pay for itself. He also launched Bailoutsleuth and Junketsleuth, hiring Pulitzer Prize-winning reporters to track federal bailout funds and government travel expenses—though neither site has been especially active. Through their film companies, 2929 Entertainment and Magnolia Pictures, he and Wagner have financed muckraking documentaries such as Food, Inc. and Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room.

I ride shotgun as Cuban pilots his black Lexus SC430 through Dallas’ Deep Ellum neighborhood, a warehouse district known for its nightclub scene. He points out buildings where he and his friends held huge parties back in the early 1990s, fueled by his newfound millions. We roll past the old offices of Broadcast.com and into a parking lot alongside a narrow building he bought as a party house and crash pad back in the day. On its outer wall is an elaborate mural of his life. It depicts his old bar, family members, and Cuban drinking with his friends in Puerto Vallarta. There’s also a portrait of “the hottest girl I ever dated” and of him in Red Square from his monthlong stint mentoring Russian entrepreneurs. The mural ends before he became a billionaire, got married, and had kids. But it’s clear that even with mere millions at his disposal, Cuban did entirely as he pleased. “I bought this building. I bought a lifetime pass on American Airlines, and I was just going to party my brains out,” he says, smiling. He might as well be describing his TV network.

MARK CUBAN is the perpetual outsider—the dot-com billionaire with little use for Silicon Valley, the TV exec who doesn’t like New York. He’s a disruptive force who follows his own impulses and insights. And that makes him an odd partner for Rather, a lifelong company man who traces his interest in CBS back to the age of 13, when he was bedridden for weeks with rheumatic fever. Every day, he would listen to Edward R. Murrow’s live CBS Radio broadcasts from war-ravaged Europe, which began with the familiar cue: “Calling Ed Murrow. Come in, Ed Murrow.” Rather idolized Murrow and, by extension, CBS News. He grew up during the Depression in a tiny house in a working-class Houston suburb, where his father managed to hang on to his job laying pipe for oil companies, but Rather saw poverty all around. As a student at what is now Sam Houston State University, he edited the school newspaper and supported himself with a gig at a local radio station, doing everything from announcing football games to fixing the transmission tower. After college, he served six months in the Marine Corps, which discharged him (honorably) after his rheumatic fever episode came to light. He worked part-time for the Houston Chronicle and then full-time for its radio station before landing a reporting job at CBS’s local television affiliate.

Impressed by his coverage of Hurricane Carla in 1961—Rather was the first person to broadcast radar images of a hurricane on live TV—his superiors called him up to the network, where he gained a reputation for hustle. He covered the civil rights movement and combat in Vietnam, and he snuck into Afghanistan to report on the 1979 Soviet invasion, a stunt that earned him the nickname Gunga Dan. “He was always pushing to get the story, really driving it; boots on ground, hand on the phone, calling,” Peyronnin remembers. Rather, for his part, idealized CBS as “this magical, mystical kingdom” where “everybody was a knight and the round table was our deep and abiding honor,” he told me. “I knew all the personalities, all the legends, all the myths. I was a true believer.” And so it was for decades—until one very big story went terribly wrong.

On September 8, 2004, 60 Minutes II aired a blockbuster piece using interviews, along with photocopied documents from a military source, to suggest that President Bush hadn’t lived up to his commitment in the Texas Air National Guard. Right-wing bloggers pounced, claiming that the documents were falsified—a notion that couldn’t be disproven without the originals. Things got worse when the source, who denied faking anything, admitted that he’d lied to CBS about how he had obtained the documents. Rather believed that his story was accurate, and he still does. But after 12 days of relentless attacks—and growing pressure [PDF] from his bosses, he says—he admitted to viewers that it had been a mistake to use the photocopies. His producer, Mary Mapes (who along with Rather broke the Abu Ghraib scandal), was fired, and three others resigned.

Six months later, Rather was toppled from the anchor chair. “He was incredibly hurt and angry,” says Jim Murphy, then his executive producer. Rather nonetheless agreed to stay on with the 60 Minutes crew. That, he says, is when he realized he was in trouble. He proposed dozens of stories but few were approved, and the handful that he completed aired in the worst slots. He believes that Viacom, which acquired CBS in 2000, was trying to push him off the show to curry favor with the Bush administration.

“The fact that he keeps making these claims is outrageous,” says Jeff Fager, the show’s executive producer, who keeps pictures of Rather on his office wall even though the two have barely spoken in years. (Rather sued CBS (PDF), in part to unearth evidence of Viacom’s political meddling, but his case was dismissed in January 2010.) “I think he was distracted, and it was hard for him to focus on just doing stories,” Fager adds. “There might be something to his crusade, that the conglomerates in media don’t want to take the chance of investing in reporting because it is risky. But not this company.”

“These are people that I worked with, I trusted, who came under extreme pressure,” Rather responds when I bring up Fager’s comment. “I’d like to think they did things they preferred not to do, such as say that I wasn’t working hard or that the quality of my work was low. Jeff knows better than that.” He pauses for a long time. “He’ll have to live with his conscience.”

Despite the troubles, it came as a shock for Rather when, in June 2006, the network declined to renew his contract. Even today, it takes considerable prompting to get him to open up about it. While invariably warm and polite, rushing to open doors for a reporter half his age, Rather harbors an old-school journalist’s reluctance to color stories with personal sentiment, even when the story happens to be about him. “I felt like hell, of course I did,” he finally admits. “I particularly feel bad for other people who lost their jobs.” He adds that he was never bitter; he had a supportive family, freedom from financial worries, and a career that had long since surpassed his wildest hopes. But Mapes, his old producer, says Rather felt betrayed. “When you work for a company for that long,” she told me, “when you cover everything from the Kennedy assassination to the Vietnam War, and then to find out that the company was not loyal back—that was really painful to him.”

Rather retreated to his fly-fishing cabin in the Catskills, where he spent the next few weeks with his family, mulling the future. “I understand retirement,” he says. “It’s just not for me. It took me about a nanosecond to say that I want to continue reporting.”

Rather has always worked at an incredible pace. When Iraqi troops invaded Kuwait in August 1990, he headed to Baghdad and landed an interview with Saddam Hussein. He crisscrossed the region for six weeks, working day and night and barely stopping for sleep. When he finally had a day off, he slept for 26 hours straight. “I kept checking on him. I was worried he had a heart attack,” says producer Tom Bettag, his coworker for 10 years. Rather didn’t really know how to do much else besides work. He spent little time at media parties and events, Peyronnin told me, because he was always too busy working or squeezing in time with his family.

After CBS let him go, he talked to news division presidents at NBC and CNN, and then execs at Fox, HBO, and Discovery. As he worked his way through the channel guide, it became apparent that the suits did not want to be associated with the National Guard fiasco. “The word came back: ‘Dan, you’re too hot to handle,'” Rather says. So he began looking for an independent outfit. He reached out to George Clooney, whom he’d profiled for 60 Minutes and who had directed and costarred in Good Night, and Good Luck, the biopic of Rather’s childhood hero, Murrow. Rather soon found himself in Dallas lunching with Cuban, who helped finance the film. “I liked the fact that he was a lightning rod,” Cuban recalls.

Cuban also smelled an opportunity. Rather was a huge name for such a tiny outlet, then available in only 4 million homes. And he could be had at a discount—roughly a quarter of his $6 million CBS salary. “I thought news on TV sucked,” Cuban explains. “It had become so corporate and ratings-driven, there was no journalism any more.” If Rather didn’t exactly fit with HDNet’s other programming, well, whatever. “Dan Rather is a personal, guilty pleasure,” Cuban says. “If it was purely a business decision, he would not be on, so it’s just my decision. That is the beauty of being an independent network. I program what I damn well please.

“I thought this was such a great opportunity,” he goes on, “not because I wanted to do a Fox or MSNBC type of thing. It was the exact opposite: I want Dan Rather being Dan Rather.” Back at CBS, news execs were always checking in on controversial stories, suggesting changes or pushing for more sources, but Cuban doesn’t meddle. And when an exposé about problems with Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner jet got the company upset, he had Rather’s back. The two men get together once or twice a year, and they exchange the occasional email, but that’s about it. “At the beginning, I had a strong sense of being alone,” Rather told me.

Cuban has also freed him from the two most pervasive pressures broadcast journalists face: ratings and demographics. When he began in television, Rather recalls, he would check ratings maybe twice a quarter, but broadcast news steadily devolved into a nightly numbers game. Cuban isn’t too concerned with how many people watch any particular show, as long as his distributors are happy and he can grow the subscriber base. Nor does he share with Rather the numbers he gets from Rentrak, a proprietary ratings service. “It’s odd, to say the least,” Rather says. “Weird.”

BACK IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, Rather is interviewing Don McLean, a real estate developer who was molested by two priests when he was 10 years old. Faced with lawsuits from dozens of abuse victims, the Catholic diocese in San Diego filed for bankruptcy protection. But a judge caught the church hiding assets, and Rather’s reporting had uncovered (PDF) a similar pattern in other dioceses. With McLean’s wife and children looking on, Rather asks him about the church’s response to his accusations, the property that the church had neglected to reveal, and how the abuse changed his life. But he avoids asking about the exact nature of the abuse. “He did come close to tearing up,” Rather muses to his crew when we’re all back in the car. “I hoped that he wouldn’t. We’ve all seen, all provoked the archetypal tearful breakdown. We were not after that today.”

Rather tends to avoid the cheap sensationalism driving today’s news cycle. His story was fundamentally about accounting—and the church acting more like a big corporation than an institution of faith. That tension, not the titillating detail, is what interests him. Each year, he puts together more than 40 episodes with a staff of 22 young producers and editors, comparable to the number that 60 Minutes produces with some 100 employees. (More than one producer laughed aloud when I brought up the size of Rather’s staff.) Nevertheless, he has reported from Iraq and Afghanistan at least six times since the show’s launch. He has journeyed to Moldova, Rwanda, Madagascar, Iceland, and all over the States; it’s a rare week he’s not boarding a plane. The day I watched Rather interview McLean, I heard his alarm sound at 6 a.m. through the thin hotel wall. He was on camera by 8 and then drove from interview to interview all day, never slowing down until 10:30 p.m., when he capped off dinner in Newport Beach with two scoops of ice cream and a yarn about crash-landing in a small plane in Alaska. It was an easy day, he quipped. “He’s 79 years old and he’s working at the same pace he did when he was 18,” Peyronnin marvels.

But does great reporting matter if nobody sees it? HDNet remains among the smallest outlets on television, and the show’s marketing consists more or less of what Rather and Cuban do in their spare time. Rather will pen the occasional article for the Huffington Post and the Daily Beast, or he’ll appear on Chris Matthews’ Hardball, but “there are only so many hours in the day,” he laments. Cuban tweets about upcoming episodes and promotes them on his blog. (“I am not a Twitter person myself,” Rather admits, though his show does have more than 5,000 Facebook fans.) Beyond that, Cuban has made little effort to extend Rather’s reach. Brian Stelter, a media reporter for the New York Times, told me he hasn’t written about Rather’s show since it first launched. “I can’t tell you when HDNet has flagged one of his big stories for me effectively,” he says, and that’s a shame, since “what he is talking about, more people should be talking about.”

Cuban’s strategy may seem counterintuitive, given that Broadcast.com made him a pioneer in putting video on the internet. “I grew up with the internet mindset—get it out there and get as many people as possible to watch it, then sell ads around it. It’s cheaper to distribute, and you have access to everyone,” he says. But he’s concluded that there’s no money in that approach—if there were, he says, NBC would have moved Law & Order online instead of canceling it. Thus, unless you’re an HDNet subscriber, you have to buy episodes of Rather’s show on iTunes for $1.99 a pop.

The big cable companies don’t like it when the channels they distribute give away too much for free—and understandably so. But that hasn’t prevented outlets like, say, Comedy Central from heavily promoting Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert and posting their best clips online. HDNet only recently began uploading promos (and the occasional segment when Rather requests it) to YouTube, where they garner maybe a few hundred views.

Rather seems unfazed that, in this era of boundless online distribution, he is essentially marooned on Mark Cuban’s tiny island. “The work is well worth doing if only one or two people watch it,” he says when I press the issue. But that doesn’t change the fact that Cuban’s model leaves him both incredibly free and greatly diminished.

And that’s an odd spot for Rather. For most of his career, he was important. He pushed back against presidents, sat down with dictators, and guided viewers through elections and national tragedies. He could have retired. CBS offered him an office and an assistant and the kind of emeritus role Walter Cronkite had. But in the end, the money, the viewers, the power he held at CBS meant less to him than the simple act of sitting down across from someone, notebook in hand, and asking questions. “I love doing news. I’d go door to door telling people the news,” Rather says. “I don’t know how long I have, but I honestly believe I can keep doing this for quite a while.”