President Kevin Baugh of Molossia.Photo courtesy of <a href="http://www.howtostartyourowncountry.com/Country/Photos.html">Everyday Pictures, Inc.</a>

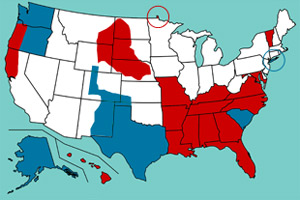

Last month, Southern Sudan overwhelmingly approved a referendum to sever its ties with the rest of the country, ending a decades-long civil war between the north and south. Almost immediately, President Barack Obama announced that the US would recognize Southern Sudan as an independent state, bringing the total number of countries recognized by Uncle Sam to 195. The total number of countries not recognized by the United States? That’s a bit higher.

While places like Kurdistan and Somaliland might occupy more of the government’s time, the ranks of aspiring nations are filled with DIY democracies—places like North Dumpling Island in Long Island Sound, and Molossia in (or surrounded by) northern Nevada—that are often equipped with little more than a flag, an anthem, and a back porch. It’s these communities, known as micronations, that Canadian filmmaker Jody Shapiro set out to profile in his latest documentary, How to Start Your Own Country. Mother Jones spoke with Shapiro recently about micro-national alliances, the future of the nation-state, and what happens when the mother country doesn’t get the joke.

Mother Jones: Your last project was about the sex lives of insects that live in your garden—how do you go from that to micronations?

Jody Shapiro: Well I had no idea about this phenomenon, really. I found this book that was written by Erwin Strauss called How to Start Your Own Country. I just thought it was this incredible idea—I had no idea that people around the world were actually doing this.

MJ: I don’t mean to put you on the spot, but I’ll do it anyway: How many countries are there in the world?

JS: We actually set up a meeting [at the UN] with a spokesperson in the secretary general’s office, and one of the very first questions we asked was what you just asked me. And their official answer was, “We are not an authority on the topic. Please consult your local library or world almanac.” They actually refused to answer that question! I think the United League of Micronations claims that there’s something like 567 countries or something like that in the world.

MJ: The United League of Micronations—is that a real thing?

JS: We tried to contact the folks, and we never got a response from anybody. So who knows!

MJ: After doing the research for the film, how many nations do you recognize?

JS: It’s hard to say. Some places—like Sealand and Hutt River Principality—I had a hard time finding somebody to give me a convincing argument why these places could not be considered countries. You go there, you get your passport stamped, you get a visa, you use their currency, you hear their anthem, you see their flag, you read their constitutions. When I left there, I felt like I was actually leaving somebody’s sovereign territory.

MJ: In the film you say there are hundreds of micronations being formed, every year—what’s the average lifespan for these things?

JS: It’s a loose term right now. It fits from anywhere from a kid in a parent’s basement, declaring his own virtual community, to places like Hutt River—that’s been around for 40 years now. I think some places will last for years; others will fold down the minute their parents kick them out of their house or something like that.

MJ: With the rest of the world stacked against them, it would seem that there’s an incentive for micronations to form alliances with each other. Does that happen at all?

JS: There was a connection between Hutt River and Seborga—they’ve done some trade summits or something. I know that Molossia has hosted a micronational Olympics. I know that [it’s] also been at war with some other places.

MJ: What happens when micronations fight?

JS: I think it probably resembles a game of Battleship or something like that [laughing]. But then there’s the story of Sealand. Somebody really tried to take it over, and they had to literally fight their way back on and deal with these criminals (as they called them), without the interference of the UK police or other law enforcement. Gregory Green of Caroline, whether you believe him or not, says he’s a nuclear nation.

MJ: What’s the difference between a micronation and your traditional aspiring nation or breakaway republic? Is Hutt River basically Abkhazia without the violence?

JS: It’s really hard to tell. And that was sort of the idea of the film; one reason that we didn’t go into some of the real-world scenarios—you know, you could talk about Palestine, or Somaliland, or Western Sahara—is we wanted to represent the idea that a country could be more than politics and policies and lines drawn in the sand, that maybe these things didn’t matter so much on the surface.

MJ: What’s the appeal? Is this mainly just a group of people who got way too into Risk?

JS: Well, you know, I take Prince Leonard [of Hutt River Principality] very seriously when he said he did it for survival. He formed a self-preservation government, which he claims was his right to do under the constitution, because his livelihood was threatened, and he felt that the only way to survive was to secede. Everybody’s sort of got their reasons for doing it, I feel.

MJ: So there’s not one unifying idea.

JS: The one thing I would say that unifies them is the nature of what makes a country a country. I originally thought it was a political question but I sort of realized through making this film that it is sort of a philosophical question. I think there is a lot of individual expression and a lot of defining who they are and this is sort of how they do it.

MJ: There are some pretty obvious steps to start your own country that everyone seems to know—a flag and a founding document, for instance. What do people tend to overlook?

JS: The responsibility of having a country. People have asked me after the film if I wanted to start my own country, and I’m very happy being a Canadian and have no desire. But there’s a responsibility that comes with [starting your own country] that I don’t think some people realize. Sealand gets requests from people looking for refugee status, leaving wartorn countries and hoping to get a passport because they see this as a country. If you take yourself seriously, there are other people in the world who are going to take you very seriously.

MJ: Starting your own country seems pretty straightforward in, say, Nevada or the Outback, where the government will just sort of smile and nod, like “Oh, this guy again.” What happens when the mother country doesn’t get the joke?

JS: It’s definitely happened in the past. Like in Sealand, the UK government tried to shut them down, there was an actual court case, there was an actual battle plan essentially drawn up, and it was ruled that they were in international waters so the UK government had no jurisdiction over them. I think President Baugh knows that if he took it too seriously, the FBI could come knocking on his door and ask him to stop doing what he’s doing. It’s a risk these places run, but a lot of them find ways to express their sovereignty despite it.

MJ: The nation-state itself is a relatively recent development, within the last few hundred years—do you think micronations are the future?

JS: It’s constantly evolving. I like the point that Gregory Green brings up in the film, which is that today, the way the world is so connected, online groups through the Internet are forming these communities that tend to be stronger than any community that certain countries can put together. Who knows what it means? One of the things that we didn’t explore in this film that may be worthwhile exploring in another film is: What is the role of the UN or other supernational bodies in the future, with the way things are still evolving? Is it still relevant?

MJ: Should they be the future?

JS: I just don’t think that there’s any stopping it. Like you said, it’s a relatively recent concept. It’s something that I think more and more people feel they have a right to define—who they are and what they are—and fix rights and wrongs and stuff, and I think it’s something that the masses are just gonna sort of move towards.

MJ: You travel to a bunch of places that our readers probably couldn’t place on a map, plus the Free State of Caroline, which isn’t even on a map. How did you make travel arrangements?

JS: Some of these places are hard to find. I say this with total seriousness: It took me three years to actually get Sealand’s Prince Michael to do an interview. I had to apply for a visa, which got denied three times, to go visit him. We eventually got permission to enter the territorial waters of Sealand. They say if you don’t have permission, be prepared to be questioned by the Sealand authorities. And if they feel like we’re trespassing, they have their measures of dealing with it.

MJ: It’s like certain parts of Idaho.

JS: Yeah, something like that [laughs]. But fortunately most of them are located near airports.

MJ: But what about going through airport security with these places on your passport?

JS: I’ll be very honest about that one. I travel too much. And I travel to the United States a lot. So I was a little concerned; I didn’t want to have any unrecognized stamps on my passport. So I actually didn’t get my passport stamped from any of these places.

MJ: If Canada—in very un-Canadian fashion—were to ask you to leave, and you were left without a state, which micronation would you join?

JS: I’m already a citizen of the New Free State of Caroline. We had the world premier at the Toronto International Film festival, and [the president] said after the first couple of screenings, he had already received emails from 20 people who were in the audience, asking for citizenship. I was quite impressed by that. I’m not ready to move into President Baugh’s backyard in Molossia.

MJ: Yeah, that sounds invasive. So along those lines, do family members and friends just go along with it?

JS: For the most part. The Seborga folks are all very serious. Even when we got there to film, there was discussion, they were a little nervous about us at first, even though we tried to arrange it beforehand. They actually put it to a vote to see if they would allow us to film once we got there.

A lot of these places are very concerned that they’re not going to be taken seriously. My biggest thing with the film was I set off to make it by saying that I was going to treat each micronational leader with the respect that they felt they deserved as the head of state. I felt they had an interesting story, and an interesting history, and I thought [Seborga] was a nice example of a town that literally the entire population believed in this idea of them being an independent principality, of not recognizing Italy.