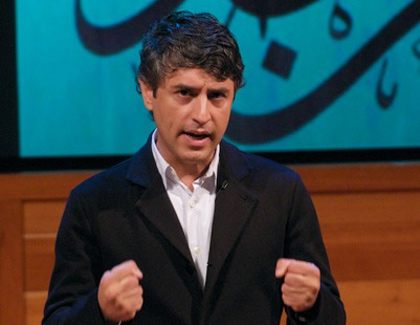

Simon Koy, courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Justin Torres didn’t grow up yearning to write a novel. He was born into a poor family in upstate New York, and spent his early years “dropping out of a bunch of colleges and working random jobs.” But when a friend in New York City invited Torres to tag along to an informal writing workshop, he unwittingly lit a spark that would turn Torres, in a few short years, into one of the most promising new fiction writers of his generation.

Torres’ recent debut, We the Animals—which promptly landed him on the bestseller lists of NPR and the New York Times—is the gut-wrenching story of, well, a poor family in upstate New York, told from the perspective of the youngest of three brothers. Lightly supervised by an abusive father and an exhausted, overworked mother, the boys run wild through town and struggle to understand their hard-knock family life and the roles they play in it. Ma and Paps are besieged by money troubles and deteriorating trust. Our unnamed narrator wrestles with a secret identity crisis. And older brothers Joel and Manny face the grim prospect of growing up to be like Paps. Torres’ prose is sparse and exacting, and he knows his characters well, as they’re based on his own kin. I sat down with Torres, who just kicked off a reading tour, in his adoptive home of San Francisco to talk about life-based fiction, the human/animal dichotomy, and how a child copes with a family that seems both to love him deeply and be hellbent on his destruction.

Mother Jones: So, how much of the book is autobiographical?

Justin Torres: The hard facts are autobiographical. I have two brothers, my mother worked in a brewery, my parents were teenagers when they started having kids, and I’m the youngest of the three. But everything that happens, all the incidents, are fiction. Nothing that happened in the book happened—or happened like that.

MJ: Was your real family as dysfunctional as your fictional one?

JT: You know, I totally bristle against words like “dysfunction” or “abuse.” I think the reason I wrote the book is because I would talk to people about my experience, and they would say things like, “Oh, you have a dysfunctional family” or whatever, and they were just these pop psychology terms, and I was like, “No! That does not describe my situation: It’s not big enough, it’s not full enough.” So I wrote the book kind of thinking about how that’s adult language, the way that adults look back and describe their experience. But how do children make sense of their world? I think the answer is magic and wonder. I don’t think that any family has a function, and I think the problem with those words is that they assume that the family is a machine. I just think that a family is. It just exists.

MJ: It does seem like the three brothers’ perceptions of what’s happening are really different from their parents’ perceptions. Is that just a product being children?

JT: Yeah, I think that there’s an openness there. As you become an adult, shame gets introduced and reintroduced constantly to you. So where something that, to a child, just is what it is—you know, your father’s violent but he loves you and that’s just the way it is—later on you realize that this is like different, shameful, blah blah blah. And so, the children in the book, they’re free of a lot of the shame that’s going to be placed on them later on. They’re able to just see and interpret things in the language of love or the language of wonder or whatever. So when the father throws the boy in the middle of the lake and is just like, “Swim!,” it’s not like “Oh, this is a moment of supreme neglect.” What he focuses on is when he comes to the surface and his father is calling his name and happy to see him alive.

MJ: Given that the book is based at least somewhat on your life, was it painful to dig up those old memories?

JT: Yeah, sure. Sometimes I would be very upset because my memories are very murky from my childhood, but there are certain emotional memories or emotional truths that are painful, and things that I know to be the case and I had to nail them down, and that was difficult. And other times I think I was trying to write my way back towards my family. If I could make characters out of these people, then I had to understand, as a writer, their motivations. I had to understand, like, why would a father punch his son? So that was a practice in empathy; it kind of expanded my conception.

MJ: Is it hard to share these sorts of things with people you’ve never met?

JT: It’s really weird, because I thought people would just be like, “OK, I see what you’re doing.” But people come with their own agendas, and they read into it whatever they want. And I have my family, who are living, breathing people that I’m very protective of, and whom I think deserve their privacy. For me, this family is not them, and that distinction is clear. But for other people, it’s not.

MJ: What was your family’s reaction to the book?

JT: Uh, my mother, at first, had difficulty with the distinction between fiction and memoir. It wasn’t like I could just say, “It’s fiction.” But we had that conversation over and over, and now she’s my biggest fan. I don’t think she’ll ever read another book in her life; she just reads this one over and over. But “autobiographical” is kind of weird term, you know? Because it’s total fabrication. I use the Frida Kahlo example a lot: You could say that she’s painting self-portraits, but she’s not, you know? She’s got monkeys on her head or her internal organs are outside her body, so you can’t say it’s a self-portrait. It’s a representation; it’s an imagining of yourself in other circumstances.

MJ: The book addresses the issues of betrayal and the lack of trust. How is it possible for this family to stay together to the extent that they do, given that they are constantly betraying one another?

JT: Yeah, that’s really astute. There’s kind of a passionate love, and an understanding of roles in the family, that makes everything okay. It’s like, we can treat each other badly, but everyone understands their role. The father is very macho, and the mother is working hard, kind of distracted, but she’s still the mother, still the central figure who keeps everybody together. And the boys are running wild, but there’s an expectation that they should run wild. I mean, they’re boys. And I think towards the end, the narrator’s sensibility, which I think is a queer sensibility…

MJ: What do you mean by that?

JT: Well, obviously as a child you don’t use words like “queer,” you know, you don’t think like that. But even as a child, I think it’s noticeable that [the narrator] is a little bit squeamish about all the violence; there’s a certain undercurrent of misogyny that he bristles against. I mean, in that culture there’s this machismo, and I think that he’s failing to own it or identify with it. And there’s a femininity or weakness in him, and there’s no space for that in the family roles. So I think that the family is able to stick together until that element becomes kind of decisive.

MJ: The kids tend to re-create the parents’ roles. I’m thinking of the scene where they’re at the playground and one brother is saying to another, “I won’t drop you” on the seesaw, but then he does, over and over. Are they aware what they’re doing?

JT: Yeah, I think they’re very, very aware that they’re enacting those roles. Children absorb the behavior that’s around them, and they reenact it. There’s another scene where they’re pretending to be the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, and the Father ties the Son to the basketball post and starts whipping him, and the son is like, “Why, Paps, why?” And that’s a reenactment of a dynamic in the home.

MJ: Is that a way for them to better understand what’s happening to them?

JT: I think it is. But sometimes there’s no answer there, and the reenactment fails in that way, because they can’t make any more sense out of it that what they’ve already got, you know?

MJ: There’s also a recurring metaphor of the boys as animals, in some cases more literally than others. Where’d that come from?

JT: It’s interesting, because I didn’t have a title as I was going through. But that was a theme, and this ended up being the title, and I’m happy with it. But I hope that, at the end, you resist the title. I hope at the end of the book that the characters are so fully human, and so complicated, and so endowed with dignity, that you’re like, “No, these aren’t animals.” But throughout, it’s what the outside world is seeing, and it’s what they’re seeing among themselves as well.

MJ: So would you say is the distinction between human and animal?

JT: Well, we are all technically animals. But I think that one the kind of defining elements of being human is our ability to make sense of the world through language, and through narrative and storytelling. And so this family, they’re doing that, they’re explaining the world to each other. But there’s such pressure on them that they’re treating each other badly, and they’re reduced often to primal needs.

MJ: Yes, they seem to be moving back and forth between the two, and somehow they kind of come out on the human side, right?

JT: I’m hopeful, yeah. And I think another thing that builds on the animal metaphor is that when you think of animal behavior, you don’t think in terms of victims and villains, or good and bad, or evil, or shame. I mean, shame doesn’t exist in the animal kingdom. It’s a human conception. I wanted to draw attention, hopefully, to the fact that if we could get out of that victim-villain dynamic, then there’s something bigger, then your mind has to hold these two very different things, like love and violence, together at once and see them together. And I think that’s more interesting. The book doesn’t really have a plot. If anything, the tension that’s pulling you through is the tension of, “Well, how should I feel about this? It’s loving and it’s fucked up at the same time, and I don’t know how to feel.” And so you keep reading to figure out how to feel about it.