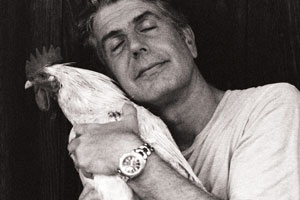

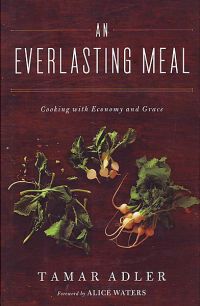

Tamar Adler, author of An Everlasting Meal: Cooking With Economy and GracePhoto by Dan Kim

Quick: You’re staring down assorted vegetable tops, three half-empty jars of condiments, and a quarter cup of last night’s takeout. What’s your first thought? If you didn’t answer “dinner,” you may want to pick up An Everlasting Meal: Cooking With Economy and Grace. Its author, Tamar Adler, has mastered the art of what she calls “catching your own tail”: transforming whatever odds and ends your pantry has to offer into deeply satisfying meals—a practice which also happens to reduce grocery bills and eliminate food waste. I chatted with Tamar about her transition from magazine editor (she worked at Harper’s) to high-end chef (she cooked at New York City’s Prune and Berkeley’s Chez Panisse) to book author, and picked her brain about kicking my embarrassing restaurant-food habit.

Mother Jones: Let’s hear about the path that you took from magazine editor to chef.

Tamar Adler: I loved my job at Harper’s, but the whole time I was there, I observed that I was thinking and creating mostly in the realm of food. I spent my lunches at the farmers market. I literally had baskets of mushrooms and artichokes in my office. I was constantly bringing in things that I had made. It took me like two years to hear a smaller voice that was like, if almost all of my energy is going into this other thing, maybe I should think about vocation and avocation and switch those around. And so I went to my favorite restaurant, which was around the corner from our office, and petitioned the chef to let me work there in secret. And pretty much she let me come in just ’cause she liked my letter (though she’s incredibly tempermental). So I cooked there for three months on Saturdays. But I felt like I wasn’t doing a good enough job as an editor and, working just one day a week as a cook, I wasn’t getting good enough for my job to be really rewarding. So I went back to Harper’s and a year later I just quit.

MJ: Since then, you’ve cooked in a bunch of places, including both New York and California. Have you noticed differences in people’s attitudes toward food and food culture in New York City versus the Bay Area?

TA: There are incredible differences. The metabolism for everything in New York is so high. So food falls into that pace. So that even though [food] is one of our basic needs, and one of the things that gives us pleasure on a much more primal and much harder to define level than something like fashion—it really is a trend [in New York City], even though it’s much more like sleep or sex or shelter. And that’s not as true in the Bay. I try not to say things like this because I think they get written off—but there is an absolute connection in the Bay Area between the way people live and where their food is grown and how it gets to them. That’s just completely absent from most people’s relationship to food in New York.

MJ: Now you’re working with kids in New York City’s edible schoolyard. That must be different from your previous gigs.

TA: Well, I was a line cook, and line cooking also is a great analogue for almost any problem solving you could ever have to do. In a battle situation, I would probably choose a line cook over a fireman.

TA: Well, I was a line cook, and line cooking also is a great analogue for almost any problem solving you could ever have to do. In a battle situation, I would probably choose a line cook over a fireman.

MJ: So if you could only write or only cook, which one would you choose?

TA: If I couldn’t cook I would write about hunger, and the hunger I had for cooking, or for food, and so in a way I’d be doing both. Because so much of cooking is about our needs and hungers, and the edges of our hunger are what makes eating as gratifying as it is. I couldn’t cook about not writing, though.

MJ: Lately it seems like we’re in an era of the chef-celebrity. What do you think that’s about?

TA: On some level, I feel like by making chefs into celebrities, we’re kind of crying for help. Look, what characterizes celebrity is its unavailability to any of us, and how little it has to do with the normal person’s life. I mean, I am grossed out by an obsessive relationship with food. Like, you want bacon in everything. Or when people feel better if they’ve been to every new restaurant or read food blogs. But, I think, again, all of that is a symptom of the fact that we know we haven’t been thinking about this in the right way, but we do care.

MJ: What’s your favorite cookbook?

TA: It’s called Simple French Food by Richard Olney. It’s so beautiful. The table of contents reads like a gastronomical poem. There are four recipes for bread and onion soups, one of which essentially is just steeping stale bread in red wine. He’s incredibly iconoclastic.

MJ: Let’s pretend I had space in my kitchen for only five ingredients, which five would those be?

TA: Olive oil. Salt. Red wine vinegar. Eggs. Then…this is a tough one. It’s either bread or something green. It’s probably a loaf of good bread. And if you could perch a head of garlic on top of the olive oil bottle, I would recommend it.

MJ: And if I just happened to make a pantry expansion and I could fit one vegetable in it, which vegetable should it be?

TA: A green, like a Tuscan kale.

MJ: Let’s pretend that I got an even bigger pantry and I was confronted in the market one day with two seemingly identical tomatoes—one of them organic from Mexico and the other local but not organic. Which one would I choose?

TA: Well, I would choose the local one, for sure. I just don’t think that food is meant to go very far. Organic is one of those words that’s obviously been emptied out. Originally it referred to a much more integrated system of dealing with food. And that doesn’t include putting stuff in trucks from another country and driving it across the national border.

MJ: Which ingredients do you think are worth buying the really good versions of?

TA: Olive oil is a really big one; it makes such a big difference. My whole way of cooking suffers when I’m in somebody’s house who has bad, or even more often bad and rancid, oil. You really taste the difference if you get a really good piece of pancetta or a really good piece of salami that doesn’t taste chemical and strange. You need actual parmesan. You don’t need a lot. Good pasta matters. And if you’re getting dried beans, it’s worth spending more. A lot of them have been sitting on shelves forever and crack and fall apart as soon as they cook. And bread. The Tartine loaf is $7, but you don’t really need to buy anything else. Good bread, some good olive oil, and good eggs (another one that really matters).

MJ: Which ingredients do you think people typically overpay for?

TA: People are always asking about different kinds of salt. Just buy kosher salt. There are a lot of high end value-added products that I think don’t really need to get bought. You don’t really need that beautiful artichoke dip or olive paste or the really fancy butter. I’m not saying those aren’t lovely things, but you can get really good organic unsalted butter, and the difference between good plain butter and amazing $16-a-piece butter is much smaller than the difference between bad olive oil and great olive oil. Precleaned lettuce is too expensive. Anything precut is too expensive—you get like half of it!

Another thing that we spend too much money on is variety. What I bring into my house starts as so few things, but then if you open my refrigerator, it’s like a wonderland in there. This has been pickled, and that’s been sautéed, and what was sautéed was turned into a frittata. But it started out being five things. The great thing about knowing how to cook is you get more variety for free.

MJ: Do you have any advice on curing my habit of going out for dinner? I get home from work and I’m tired, and I usually want to hang out with a friend or two, and going out for dinner seems like a great convenient way to do that.

TA: You know, I’m almost always feeding somebody. There’s almost always somebody else at dinner. So I’m going to answer the question backwards. Part two is, as long as you’re comfortable feeding well-loved but incredibly humble things to your guests, you can always have someone over. People love it! When people are coming over, I’m always telling them, “I’m totally going to not just make some assembly of what’s in my refrigerator.” But that’s never true. I always spend too long reading, and suddenly it’s 5:30, and then I’m like okay—frittatas again. But it doesn’t ever look or taste to me or anybody else like some weird impoverished experience. Eating just has to be ordinary. Cooking has to be ordinary. We’re wrong when we think that as soon as we invite people over, we have to do something out of the ordinary.

MJ: Another problem, I’m embarrassed to say, is laziness. I like cooking, but I don’t have the energy after work. Any advice?

TA: At lunchtime today I had purple sautéed escarole with lentils, which I warmed together and then put chilis on top. And it took me like less than two seconds to make. Because I’d already washed and dried the escarole and put in a great container. And the garlic is always sitting in a bowl on my counter. And I cooked lentils like four days ago, but I cooked them alone and I cooked a lot of them. You come home and you can assemble your meal the way I did, or you can just warm the lentils with a few tomatoes and poach an egg in it, or you can make rice and add Indian spices to the lentils. I pretty much never cook from the beginning.

MJ: It seems like wringing the last bit of use from leftovers requires shedding popular ideas about expiration dates. How can I get over my squeamishness?

TA: We’re the only culture that relies on refrigeration so heavily. Refrigeration has ruined everything. It’s made our food worse, and it makes us throw out things we need to make good food. In England, eggs aren’t ever refrigerated. Same in a lot of places in France—meat is stored at room temperature if it’s stored under fat. Pickles will be stored in vinegar for months and months. We used to keep pies for weeks and weeks in our pie boxes. People also died of food-borne bacterial illness more then, but somewhere in between weeks and weeks and this one-day thing. Really look at other cultures, and if it takes imagining yourself as a Burgundian housewife, do it.