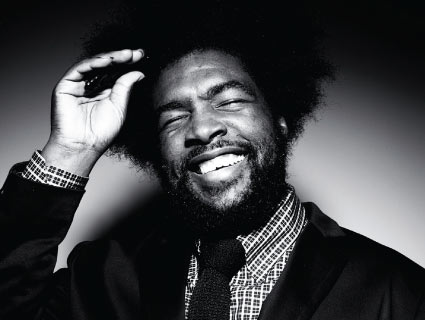

Photograph by Robert Trachtenberg/Corbis Outline

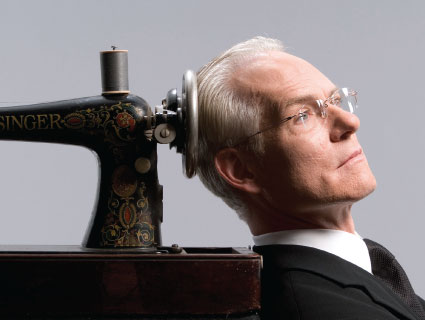

If Tim Gunn had his druthers, he’d spend most of his time alone: “I’m one of the biggest introverts you could ever meet.” But the 58-year-old fashionista rarely escapes the spotlight these days. Besides his celebrated stint as Project Runway‘s mentor extraordinaire for nine seasons and counting, he’s chief creative officer for Liz Claiborne, author of three books, and cohost of The Revolution, a new lifestyle talk show premiering January 16 on ABC. Before he became a star, Gunn spent 24 years at Parsons The New School for Design, which segued nicely into his role as one of America’s top arbiters of chic. Gunn talked to Mother Jones from his home in Manhattan, where he takes public transit and insists on being a regular—if impeccably well-dressed and extremely polite—New Yorker.

MJ: Do people hit you up for fashion tips on the subway? Because I’m guessing you’re not an earbuds man.

TG: No, I’m not. Laughs. I had a guy who said “I’m sorry to bother you, but do you mind if I ask you a question? Where can I find suits that fit me?” And I said: “Can I touch you?” And he said, “Yes.” So I put my hands on his shoulders and I pushed them back, and I said, “Now straighten your spine.” And he did. I said, “You’re suit fits you perfectly fine. It’s your posture that’s a problem. So, stand up straight!” People do ask. And I’m flattered. If it’s really atrocious, I’ll say, “Well, you know something? If this is the look you wanted—it’s a fabulous one.” It’s a line borrowed from I Love Lucy.

MJ: You have become one of the great TV father figures. Maybe not since Fred MacMurray have we had someone like you who’s unequivocally there for us, but who also sets parameters.

TG: Aw, well thank you. I deliver tough love when I need to!

MJ: Why do you think Project Runway has had such staying power?

TG: I’m as wowed by the whole phenomenon as anyone. I had the mother of a nine year old tell me this in an airport. She challenged me, she said “I’ll bet you don’t know why I love the fact that my daughter loves the show.” And I thought to myself, “Well, I bet I do.” But I didn’t! She completely stumped me. She said, “I love the fact that my nine year old watches the show because the show teaches you that good qualities of character are important. Hard work pays off. It’s better to play nicely with others than to be a diva. Cheaters never prosper.” And I thought, “Good heavens! I’d never thought of the show from that point of departure, she’s right!”

MJ: You may also have the best tagline ever, Don’t. Bore. Nina. It captures the show’s ambition and you so perfectly, yet even if you don’t watch the show or know who Nina Garcia is you can take it to heart, challenge the mundane!

TG: [Laughs] Yes! Exactly. There’s a great moment which, for some reason they didn’t leave in the show—The judges are engaged in the Q&A with the designers on the runway. And Nina, at one point, puts her hands over her eyes and she calls out “If I see one more off the shoulder dress, I’m going to scream! And Michael Kors takes one of her arms, removes it from her eyes, and says “Nina, how many neckline treatments are there? I can count them on one hand.” I thought that was a great moment. Put the whole thing into perspective.

MJ: You’ve said you’re “constitutionally incapable of being snarky.” How can the rest of us avoid it?

TG: Take the high road. No matter how much strife, and consternation, frustration and anger you might be confronted with—don’t go to that level. I’ve never ever regretted not taking the high road. And I’ve frequently regretted lashing back, sending that angry email. I always say: write the email, don’t send it. When it comes to face-to-face confrontations of the sort, it’s even better to take the high road. It’s just…you’ll feel better about yourself. There are things that you undoubtedly want to say to that person. And I do—in my head—but I don’t practice it, I don’t actually do it. Though, I will say—and I came to this realization from dealing with my mother, may she now rest in peace—I will say that the high road can get so high that you can get a nose bleed, in which case you have to get off the high road.

MJ: You spent all your allowance on Legos as a kid, did they play a part in you learning about color schemes and structure, or is that kind of learning innate?

TG: I don’t know why I’ve always been so captivated by architecture. I think it’s that introverted, inclined-to-nest person in me. I’ve always liked miniature rooms. My sister—she’s three years younger—when Barbie came out, I loved Barbie’s houses, and the play sets more than I even loved…well, that’s not true. I loved her and her clothes. But I liked making those things. And my mother would tell the story of going to visit Monticello, Jefferson’s home in Charlottesville, when I was 9. I used my allowance money to buy a book of his architectural drawings. So, I was fascinated by architecture, by Palladio, by the Golden Mean. And I read a lot, and I studied those images. And I think—I mean, I don’t think, I know—that it had a profound impact on how I looked at the world and how I organized the world and how I, in a manner of speaking, designed the world. So, I believe it’s so important to have good, classic examples so then–if your intention later is to break the rules—at least you know what those elements and dimensions are.

MJ: Your dad was an FBI agent under J. Edgar Hoover, how did his job influence you?

TG: I was very proud of him. But he was especially close mouthed about his work. There was one time I remember, when the Warren Commission draft report came out and he had it in the house to read it over the weekend. My mother found it, went into the bathroom, locked the door, got into the bathtub, and read it. And Dad somehow found out, and to make a very long story short—because there was lots of yelling through the door, both directions—he took out an ax and chopped the door down.

MJ: Wow.

TG: Laughs. It was dramatic!

MJ: Definitely, and fascinating.

MJ: In 2010 you did a clip for the “It Gets Better” campaign encouraging gay young people. What was growing up like for you?

TG: Part of what was in the ether all around me growing up, until I was between 19 and 20, was a terrible, debilitating stutter. It was part of what made me very reclusive as a kid. It was after I’d had a lot of speech therapy that things really got better for me—because I had more confidence in myself. That’s what at the core of all this. I’ve been in situations where I’ve said to young people: “You’re so personable, you’re so articulate, you’re clearly so bright, you’re so good-looking—feel better about yourself!” But if at the core if you don’t, all those words mean nothing. Absolutely nothing.

MJ: It got so bad you attempted suicide, did you have a mentor or someone else who helped you up at that time?

TG: No, I really didn’t. That’s part of what my desperation was all about. I had gone to, oh, probably half a dozen different psychiatrists. And they were not helpful experiences for me. I wasn’t willing to speak about things that were important to talk about. When I think about things happening for a reason—it wasn’t until the suicide attempt, which was actually quite a serious one, that I was forced to confront all this.

MJ: What role do you think reality TV has played in American’s acceptance of gay culture, or at least familiarity with it? Shows like Queer Eye and Project Runway, they seem to have humanized the unknown.

TG: You said it perfectly. It’s humanized the unknown. You’re absolutely right.

MJ: Project Runway runner-up Mondo was HIV-positive and made clothes inspired by the positive (+) sign. Do you think fashion can be revolutionary?

TG: Oh, absolutely. Well. Yes, it can, and we have plenty of examples where it has been. I have to say, though, for me, the climax of the fashion revolution was the 1960s. I can’t imagine another period happening that will ever be even remotely equal to that, when I really reflect upon that decade. When you think about how we led into it with a Mad Men primness, and we leave it with hippiedom. And in between, we have the miniskirt. We have the clear vinyl dress. We have the paper dress. I don’t think we’ll ever be shocked again. Think about Barbara Streisand accepting her Oscar for Funny Girl in that Arnold Scaasi pantsuit that was practically transparent.

I would always ask my students if they’re choosing fashion, “How many of you in this room can tell me when World War II happened? And there’s this audible groan that comes up from the class. I would continue to ask the question each semester the reason being America was a nation of fashion copiers until World War II. It was about going to Paris specifically, looking at the collections, and then literally copying them and bringing sketches back, and photographs, and then copying the works here. I mean, Ohrbach’s—that retail powerhouse—was all about copying Paris. So when World War II happened, and all the couture houses closed, there was nothing to copy. So suddenly there has to be some creative and innovative thinking in this nation when it comes to fashion.

MJ: How did your own personal style evolve?

TG: My role as the chair of the fashion department at Parsons put me face to face with all the big designers, retailers, and editors. Since I was moving in these new circles regularly, I realized I needed to do something about my own personal style. It was really Diane von Furstenberg who gave me the nudge. She said “Darling, you really need to do something about this look of yours.” I needed to look a little hipper, a little more modern, and a little less stuffy. If you can believe it there was a time when I was even stuffier than I am now.

MJ: You’ve said that no one’s too smart for style. And there’s that moment in The Devil Wears Prada where Meryl Streep does this takedown of the smart girl for thinking her regular blue sweater is fashionless. Why do we think it needs to be an either or, intellectual or fashionable, or is that changing?

TG: Fashion is the F-word in that world. One of the first meetings I went to as [Parsons design] department chair the head of the Economics Department said to me: “If I’d known you were going to be here, I would have brought my jacket with the missing button.” Can you imagine? Of course, later I thought of the perfect retort: “Well, if I’d known you were going to be here, I would have brought my taxes.” People believe that if you’re concerned about the clothes you’re wearing and the larger aspects of your appearance, that it’s anti-intellectual. I say “Hogwash!” The clothes we wear send a message about how the world perceives us. And then people will say to me, “Oh that’s so shallow, that’s so inconsequential, don’t say that.” Well it’s true! Let me put it this way: When someone new walks into a room, the first thing we notice about that person is probably their gender. And the second things is what they’re wearing. And based on what they’re wearing, we start making certain assumptions about them. And people will shout back at me “I don’t do that!” To which I respond: If you’re at a cocktail reception, how do you know who the wait staff are? You know by how they’re dressed! I would never dream of telling people how to dress. but I do say to them, however you are dressing, accept responsibility for it. And also, unless asked, I don’t judge. And if asked to judge—I would approach it socratically, I would approach it with questions. Because I say all the time: That person on the street who looks like a circus clown. Maybe they are.

MJ: Is fashion misunderstood? What would you say are common misperceptions?

TG: Well. That somebody who cares about clothes is missing something intellectually and spiritually. And that it really doesn’t matter. It does matter. And I will also say—as disturbed as I am by people wearing sweats to the theater I’m just as disturbed by fashion victims. By people who have to have the latest thing. When they’re head to toe in expensive designer clothes and accessories. I’m just as unnerved by that. So, I like striking a happy balance of those things. And being yourself. That’s what’s so critical. One of the fashion icons I have is Martha Stewart. People say “Martha Stewart?!” Martha Stewart’s figured out how to present herself to the world. You know it’s Martha. She looks sophisticated and polished.

The red carpet is a whole other matter. I look at red carpet clothes the way I look at wedding clothes. They’re so occasion-specific, they’re not really meant for navigating the real world. But I’m frequently taken to task by other commentators, or by the press. For instance, I think it was the 2008 Oscars where Tilda Swinton wore that black Lanvin cocoon. And I thought it was magnificent—that she was magnificent. Spectacular. She was one of my top picks for the red carpet. But I was attacked on The Today Show the next morning by Stacy London saying “you’re crazy, that black plastic garbage bag? Who would wear that? Who could wear that?” I said, there’s one person who can wear that, and that’s Tilda Swinton! I’m not talking about taking that dress off of her and putting it on Sally Field. It’s about the semiotics of clothes! That dress sends a message that says “I’m not marching to the beat of everyone else. I’m not a classicist, I’m a bohemian. And I listen to my own voice. That’s what that said. How magnificent a statement is that?

MJ: And yet, some people feel like fashion’s inaccessible. Like, why is Anna Wintour, and the word couture for that matter, so intimidating?

TG: Well, Anna Wintour is intimidating. But that’s because she’s made herself intimidating. She does not have a Socratic approach to anything. She just lays down edicts. And whether you’re the editor in chief of Vogue or you’re a college professor—that’s bad. It’s simply not the way to operate. And the word couture—it’s so wrongly used. And I’m constantly correcting young people and fashion students in this nation when they say “Well, I do couture.” By definition, you don’t. You have to be licensed by the government of France to do couture. So don’t use that term. You can say that you do one-of-a-kind, you can say it’s custom, but you can’t say it’s couture—because it’s inaccurate. Today there are seven couture houses in France. In the 1960s—you won’t believe this—there were more than 200! Can you imagine even naming 200 designers? I can’t. But, they are intimidating. And I will also say, I really love shopping on a budget. Personally, but also for everyone else. I find the whole notion of the multi-thousand dollar dress to be thoroughly repugnant. It’s not necessary. It’s how I feel about Kim Kardashian’s $2 million engagement ring. How about spending 1.5 million, and giving half a million dollars to charity?