Los Restos De La Revolucíon by Kevin Kunishi

Daylight Books

For those of us under 40, the Central American wars of the 1980s remain a kind of hazy point of international political awakening, if they register at all. Through the ’80s, the world outside of home, school, and my Midwestern hometown came into sharper focus. These places south of the United States—El Salvador, Panama, Nicaragua, as well as Grenada—existed in the background as bits on the nightly news, occasionally pieces in the newspapers and magazines and, as I grew older, recurring references in the punk music I discovered.

Kevin Kunishi’s interest in the Cold War battleground of Central America, Nicaragua specifically, was sparked while he studied history as an undergrad at the University-California Santa Barbara in the early 2000s. Pursuing his interest in the region, Kunishi visited the the still-healing Nicaragua in 2009 and 2010, 20 years after the war, well after Americans stopped caring. And really, it’s not like most Americans ever cared that much, even when the bullets (that their tax dollars helped buy) were flying.

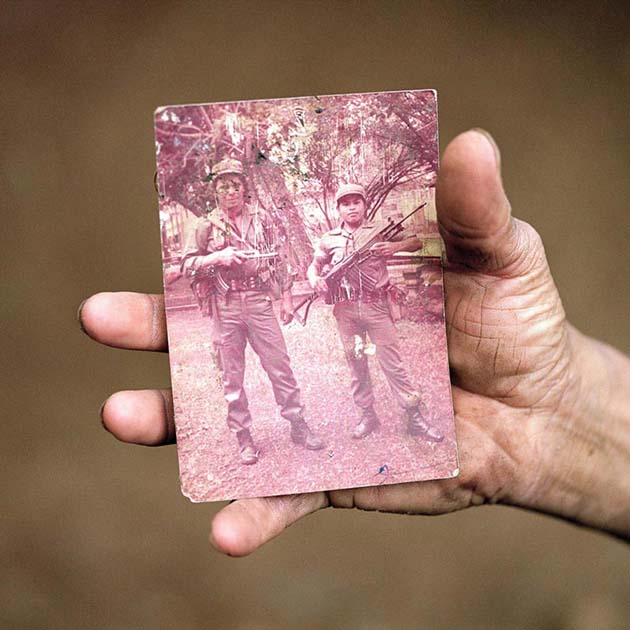

In his first book, Los Restos de la Revolucíon (The Remains of the Revolution), Kunishi takes us to the mountains and jungles of Nicaragua, showing how the land and people have reconciled with a decade of war. A bucolic shot of a green hill poking from a mountain was the site where a Sandinista helicopter crashed. A simple image of a tree branch carries extra weight when you learn it is at what used to be a prison run by the Somoza regime. From that branch prisoners were hung upside down and tortured, often until death.

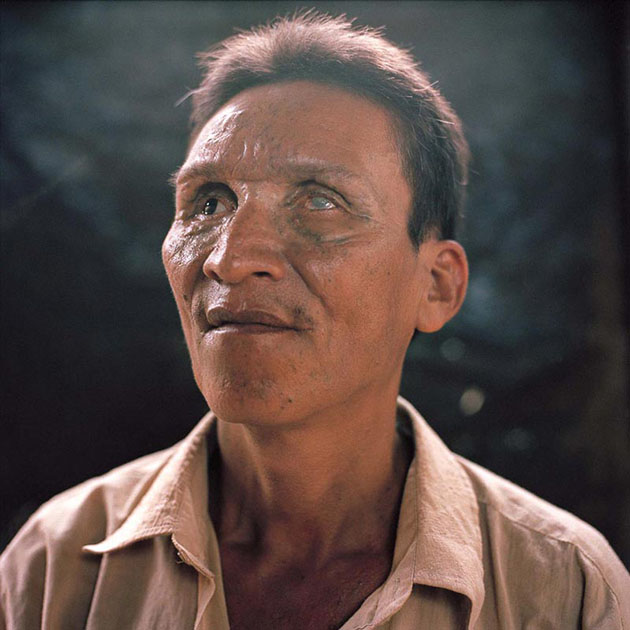

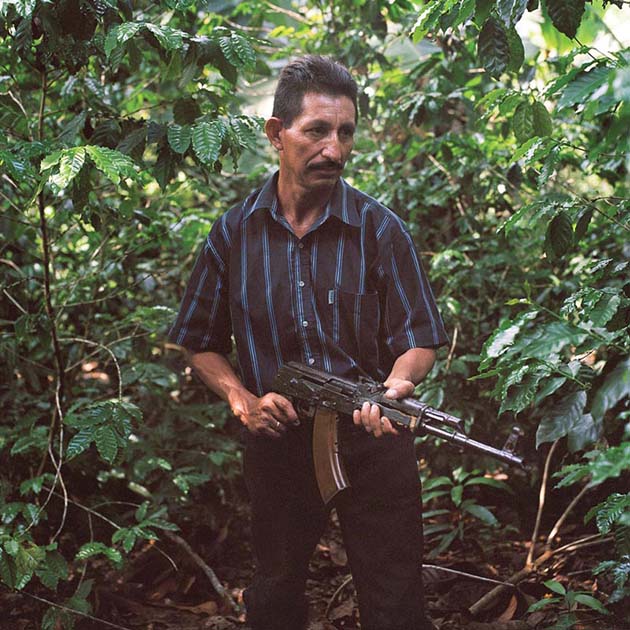

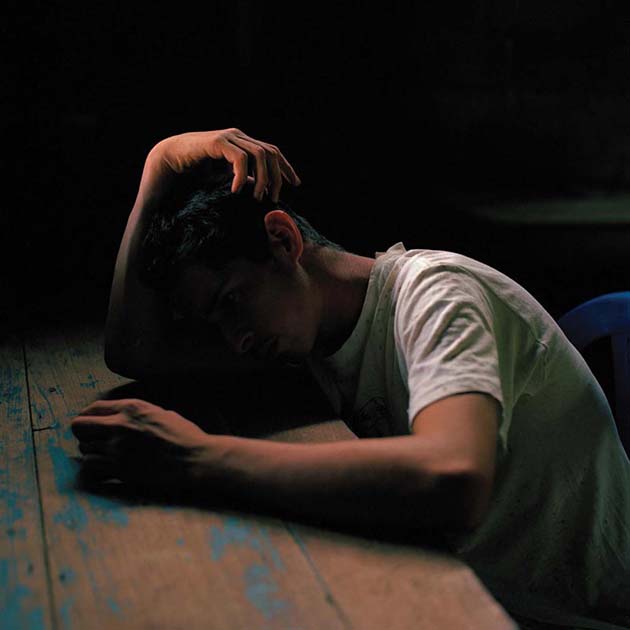

Kunishi connects with people who’ve lived with the legacy of the war: a former Contra rebel blinded by a grenade attack; a Sandanista solder who lived with 40 others in a tiny cell for three months; and the younger generation, teenagers graduating school, who offer evidence of a country moving strongly in a new direction.

The photos have a fine-art bent to them, part of the current canon of photography that proudly blurs the line between photojournalism, documentary photography, and fine art. The photos document, they tell a story (even if that story is the afterward) and yet they’re easily at home in a gallery, if not on the wall of your home. There is an eerie stillness to many of the images, which is not unlike what I image visiting these sites would be like. The sound of chirping crickets and an uneasy wind rustling nearby trees is all that’s missing.

Those in the Bay Area have an opportunity to meet Kunishi and see the images as lush, lively prints at his exhibition opening and book launch, held at RayKo Photo Center in San Francisco on October 11. Everyone else can indulge themselves in the succinctly edited book, Kunishi’s debut monograph, out on Daylight Books in November.