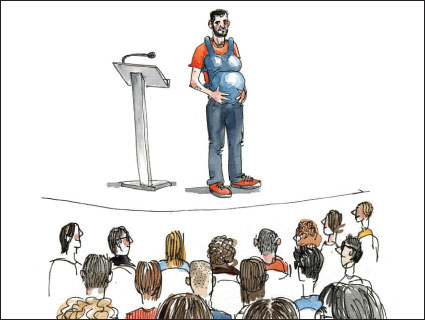

Steven Leckart's pregnancy suit.Wendy MacNaughton

It was in late 2008, with the economy in free fall and magazine publishers ever more desperate for a digital strategy to save their asses, that San Francisco-based journalist Douglas McGray had his aha moment. A former editor at Foreign Policy who’d turned free agent to write features for outlets like The New Yorker and the New York Times Magazine, he had recently begun to branch into radio, producing occasional segments for This American Life. It suddenly occurred to him that he knew tons of writers, but very few radio people or filmmakers or photographers. “I just thought it was weird,” McGray, a soft-spoken 37-year-old, told me recently. “We’re supposed to be in this multimedia age, and the professions are still fairly separate.” And then came his epiphany: What might it be like, he wondered, if you reimagined a magazine as a stage performance?

That idea, fleshed out with collaborators Derek Fagerstrom, Maili Holiman, Evan Ratliff, and Lauren Smith “at two or three kitchen tables and a couple of bars and coffee shops,” culminated in Pop-Up Magazine, a live event whose first “issue” was held in a 350-seat San Francisco theater. “We thought it was a ludicrously huge space,” McGray recalls. But they filled it. And Pop-Up (whose nonprofit accounting is handled by MoJo‘s parent foundation) is now the hottest ticket in town—Issue No. 7 (which happens tonight) sold out the 2,740-seat Davies Symphony Hall in about half an hour. But it’s not necessarily a showcase for rock stars. “There are people who are well-known literary performers,” McGray says. “They’re actors, really. They’re pros. We wanted to create a format where you didn’t have to be like that.”

You never quite know what you’ll get. (The lineup is a closely guarded secret.) It might be Wired contributor Steven Leckart displaying a strap-on pregnancy suit that gives men a taste of their expectant wives’ burden. Or the director of Toy Story 3 showing how he grafted snippets from a dozen Tom Hanks vocal takes into a brief, heartfelt speech by Woody. In one issue, filmmaker Charlotte Buchen did a moving piece on a Pakistani pop star turned devout Muslim, and Times Magazine contributor Jon Mooallem, a regular, recounted a politician’s attempt to bring commercial hippopotamus farming to America in the early 1900s. In another, author Laurel Braitman profiled an obsessive squirrel fancier who later became a student of Sigmund Freud. Everything’s live: music, interviews, recipes, even ads—which tend to involve cocktails. “It occurred to me,” McGray says, “that you could put really phenomenal filmmakers who were just filmmakers alongside writers who were just writers alongside photographers who were just photographers.”

The shows are unrehearsed (no fiascoes yet), everyone gets paid, and, blessedly, Pop-Up remains that rare had-to-be-there experience—no photos, iPhone videos, or live tweeting, please. “We thought, ‘Well, let’s just make the show for the people in the room,'” McGray explains. “It was nice to just ask people to unplug for a couple hours. A friend of mine was sitting in the balcony and he said it was maybe the only time he’d ever been to a live thing where he’d look down in the audience and he couldn’t see a single glowing screen.”