An Afghan soldier protects his face from a dust storm.Balazs Gardi / Basetrack.org, Creative Commons.

In late May, the Chicago Sun-Times took the unprecedented move of gutting its photography department by laying off 28 full-time employees, including John H. White, a 35-year veteran who had won the paper a Pulitzer. The nation’s 8th largest newspaper figured it could cut costs by hiring freelancers and training reporters to shoot iPhone photos, to which Chicago Tribune photographer Alex Garcia responded: “I have never been in a newsroom where you could do someone else’s job and also do yours well. Even when I shoot video and stills on an assignment, with the same camera, both tend to suffer. They require different ways of thinking.”

Experimenting with iPhone photography is nothing new for journalism outlets. During Hurricane Sandy, Time turned over its Instagram feed to five photographers who delivered an eerie, often radiant record of the storm and its aftermath. (One of Benjamin Lowy’s iPhone images graced the print magazine’s cover on November 12, 2012.) Time deemed the experiment a success: Its Lightbox photo blog garnered 13 percent of its overall web traffic during the week of Sandy, and its Instagram racked up 12,000 new followers in 48 hours.

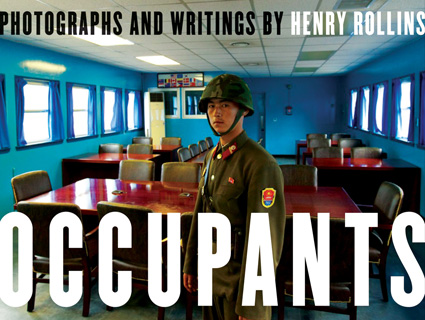

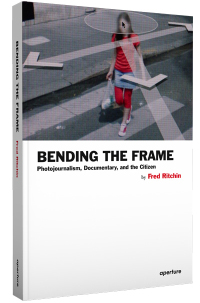

In his new book Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen, photographer Fred Ritchin tackles these developments and more as he explores what the digital revolution means for his trade.

His own résumé includes stints as a photo editor for the New York Times magazine and the executive editor of Camera Arts, as well as a Pulitzer Prize nomination for his work on the 1996 website Bosnia: Uncertain Paths to Peace. Ritchin also cofounded PixelPress, a website devoted to helping humanitarian groups develop innovative media projects. He now codirects the Photography and Human Rights program at New York University.

Bending the Frame is a vigorous wake-up call to photojournalists to innovate or die. Photographers, Ritchen writes, should continually be asking how they can create more meaningful imagery rather than just chase the “trail of the incendiary.” I asked Ritchin to fill me in on the details. Interspersed throughout the interview are examples of photographic projects that he considers particularly innovative or audacious.

Mother Jones: What do the Chicago Sun-Times’ recent layoffs mean for photojournalists?

Fred Ritchin: The layoffs ask: What does a professional photojournalist do that others cannot? Depicting photo opportunities as if they are authentic, covering press conferences, or making subjects play their assigned roles (the poor as passive victims, celebrities as glamorous) are hardly adequate responses. In fact, these might be reasons to ask for the help of amateurs who do not know how to stylize their imagery and are not interested in making a publication seem more palatable to its potential consumers.

There is enormous need for professionals who know how to tell stories with narrative punch and nuance, who can work proactively and not just reactively, and whose approach is multi-faceted. We need more “useful photographers.” Given today’s budgets for journalism, my guess is that quite a few photographers will be fired in the near future. But I certainly hope that many visual journalists will be hired or funded along the way as well—we urgently need their perspectives.

From the 2001 series “Last Supper,” by Celia Shapiro.

MJ: The Chicago Sun-Times plans to train reporters in iPhone photojournalism. Will that change how reporters approach stories?

FR: There are very few instances where writers have also been effective image makers—different skill sets are required. I do not expect this experiment to be very successful unless these reporters can be trained to evolve into multimedia journalists; word, image, and sound all must have primacy in the development of the narrative.

MJ: Have the ethics of photojournalism changed in the age of the smartphone?

FR: Photojournalism has become a hybrid enterprise of amateurs and professionals, along with surveillance cameras, Google Street Views, and other sources. What is underrepresented are those “metaphotographers” who can make sense of the billions of images being made and can provide context and authenticate them. We need curators to filter this overabundance more than we need new legions of photographers.

The ethics, to answer your question, have certainly changed: Many who are making cellphone images are advocates with a stake in the outcome of what they are depicting. In some ways this makes their work more honest and easier to read—they can also manipulate, although the work of professionals can be quite manipulative as well.

MJ: Last year, Time got a lot of praise for its Instagram coverage of Sandy. Does this hunger for real-time documentation and sharing affect the quality of photojournalism?

FR: There is room for all kinds of points of view. Certainly everyone should be encouraged to weigh in on their own experiences of a massive storm or other such disruptions, but not everyone is qualified to explain how such storms fit into climate change, or what needs to be done to try and prevent or minimize future disasters on this scale.

MJ: You argue that we can appreciate the democratization of social media without having to consider every image successful. What defines a successful image on, say, Instagram?

FR: We have a long history of snapshot photography that appeared to many to be more arbitrary and idiosyncratic than much of the work of professionals. We valued it for what it could tell us about the details of people’s daily lives. The same happens with social media when the person making the imagery is engaged with what is happening around him or her, rather than simply trying to stylize the image for effect or compete with others to show how their life is, or appears to be, more exciting.

MJ: Google Glass promises real-time video sharing, and Instagram recently introduced video capabilities. Do you see video supplanting photography as the visual medium of choice for journalists?

FR: It’s not a competition, but a question of synergies among all media, particularly on a digital platform. Multimedia is not more media, but the employment of various kinds of media (and hybrid media) for what they each offer to advance the narrative. The inherent non-linearity of the digital also allows for more input from others, including the subject and reader as collaborators. The top-down, bedtime-style story is of limited use. A non-linear narrative that allows for increased complexity and depth, and encourages both subject and reader to have greater involvement, will eventually emerge more fully from the digital environment. This, in a sense, is the more profound democratization of media.

MJ: As a magazine photo editor, what did you value in a shot? How did you balance the aesthetic with the need to illustrate or inform?

FR: Photographs need to demand the viewer’s attention, often implicitly, posing questions as to the nature of what is being depicted. Photographs are not there to show us the world, but to show us a version of what may be happening. The ideal scenario is one in which the reader is motivated enough to become actively engaged in establishing the meaning of the imagery.

MJ: Is contemporary photojournalism more about daredevilry and showmanship than nuanced storytelling?

FR: In recent years the tendency has been to elevate the messenger over the message, a strategy which effectively keeps their more painful imagery at a distance. The courage of the photographer is celebrated while the circumstances of his or her subjects becomes somewhat secondary. As a result the photograph becomes less of a window onto the world and more of a mirror reflecting the distorted priorities of the culture consuming the imagery.

MJ: Who are some news photographers—or media outlets—that take substantial aesthetic risks?

FR: In the early days of print magazines during the late-1920s and the 1930s, publications like Vu and Regards emerged in which the formal elements were designed to amplify the messages of the photographs, often in idiosyncratic and even astonishing ways. One had to read the visual elements of the two-page spread and not just rely on the captions to establish the meaning of the photographs. Then, more pre-formatted magazines such as Time and Newsweek appeared that emphasized the photograph for its content without significantly playing with the design of the page. Now we’re at the mercy of online content management systems that are highly efficient, allowing text and image to be plugged into a pre-existing layout, but lack the possibility of establishing emphatic visual statements that are tailored to a particular point of view—it is largely chaos, more reminiscent of the design of brochures than of sophisticated visual publications. Certainly many photographers push the envelope in terms of form, but one is more likely to see their work in books and galleries than in news publications.

MJ: In Bending the Frame you mention Here is New York, a much-discussed exhibition that bore photographic witness to 9/11. How can we rally people around photos of less momentous or charged events? As far as the general public is concerned, is photojournalism just disaster porn?

FR: Shortly before that project began, our own online publication, PixelPress, had invited people from around the world to send in imagery and texts responding to the events of September 11. Since most of our respondents lived far from New York, we had many compelling metaphorical uses of imagery—a series of large-format photographs that showed only dust, an empty bench from a Swedish photographer, a multimedia piece showing an eternal flame with an endless column of posters of the missing, etc. This was far from disaster porn; it was often intense, a form of grieving. Certainly people can rally around all kinds of causes and events from climate change to gun violence, and they do. JR’s Inside Out is one newer model.

MJ: Many of the most consequential issues of our time—climate change, genetic modification, economic disparity, global population growth—remain relatively underrepresented in photography. Why? What needs to happen for this to change?

FR: As we deal with issues of this enormity, many of them planetary in scope, we need to work at a different scale, using data visualization, GPS mapping, various kinds of filtering which allow the reader to compare people’s lives across local and national boundaries. One cannot always summarize such massive issues by looking at the life of one person or one family, or even one community.

Jonathan Harris’s storytelling platform Cowbird and the website 7 Billion Others are two substantial attempts to interrelate our individual stories with those of others. We also have to be more creative in using digital photography, which is code-based, to explore issues of our own code, DNA, and that of plants and animals, in ways that analog photography, with its concentration on the phenotype, has been unable to do. There are enormous possibilities for mapping data visually, for exploring hypotheticals, for working on solutions rather than just showing the problems.

MJ: How would you describe the differences between recent photojournalism from Afghanistan and Iraq and that from the first Gulf War? Was government involvement or oversight different?

FR: During recent wars, photographers have been embedded with restrictions placed upon the kinds of imagery that they could distribute, while during the first Gulf War they were largely kept away from the conflict. Both systems are highly flawed. It is no accident that so much of the most important work by photographers has been on veterans as they return to the United States—one has more freedom in how one photographs.

MJ: One of the most fascinating parts of the book concerns humanitarian and NGO photography. This is an area where a image’s credibility and rhetorical power are crucial, yet so much of what’s produced is almost propaganda. What do you see as the responsibility of an American photographer working to raise awareness or aid in a foreign country?

FR: The ideal relationship is for the photographer to work on an extensive documentary project (if they can find the financial support), and then for an NGO to find that there is a shared interest in that particular region or issue. Making imagery to conform to an NGO’s mandate is a slippery slope which can be effective in publicizing a crisis but can also be inauthentic, a form of advertising. There may be short-term gains but a long-term loss of credibility.

MJ: You bemoan the limited capabilities of online photo presentations. Is the slideshow format dead?

FR: The slideshow is not dead nor about to die, but it should not be the default mode of presenting images. It’s a very primitive form that quickly becomes predictable and repetitive. When we worked on PixelPress we never used a content management system; we tried to design each project on its own terms so as to make it the most articulate possible. This is by far the best way to work with imagery although certainly not the cheapest.

MJ: Speaking of cost, given the glut of affordable freelance and agency photography, what is the incentive for publishers to send photographers on assignment?

FR: The incentive is simple: to uncover that which is authentic and important, and to share it with the readers in a compelling manner.

MJ: The photos throughout this interview are examples of projects that you find particularly innovative. What do you like about them?

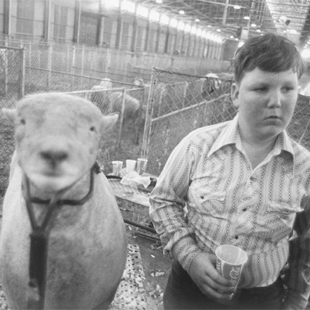

FR: They make the reader think, rather than recycling the same kinds of images. What does it feel like to be a veteran stateside but still concerned about snipers? What does a prisoner choose to eat just before being put to death—what does it say about the person, the institution, and the larger society? What if soldiers and the battlefront were shown as if in a family album, rather than as distanced and outsized, and discussions were invited from family members, as happened in Basetrack? What if images of a previous conflict, in this case the Sandinista revolution, are shown outdoors in the places where the events occurred so that a younger generation has to confront a history that may have remained somewhat remote—and does that encourage reflection from others around the planet who may be oblivious of their own histories?

MJ: What is the relationship between good citizenship and photography?

FR: Citizen journalism is not only sending in comments and making images with cell phones, but also supporting good journalism, including photography, made by others so as to help all of us better understand what is going on in our world. That support can entail crowd-sourcing images (see the New York Times’ section “Watching Syria’s War”), responding to coverage made by others with one’s own specific knowledge and point of view, and helping to pay for work that only professionals could accomplish. Citizen journalism is not only the right to self-express, but the right to act like a citizen and not a consumer.

For more, check out these photo essays:

|

|

Inside Libya With Only an iPhone Inside Libya With Only an iPhone |

|