“There are two ways to tell the story. Funny or sad. Guys like it funny, with lots of gore and a grin on your face when you get to the end. Girls like it sad, with a thousand-yard stare out to the distance as you gaze upon the horrors of a war they can’t quite see.”

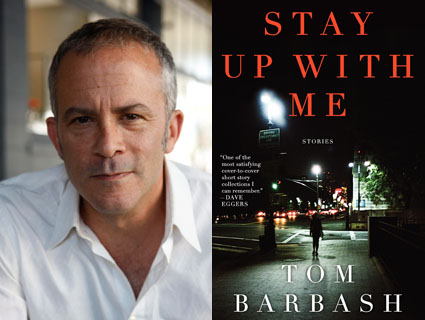

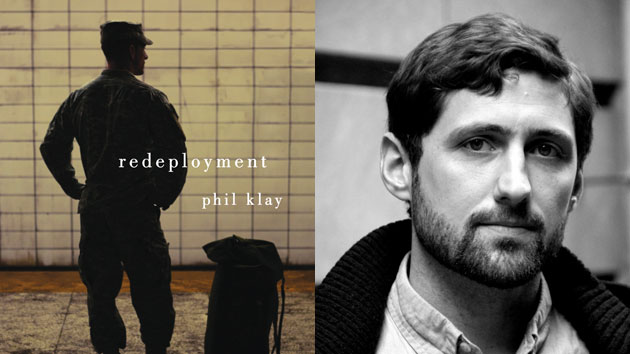

That’s the beginning of “Bodies,” the most darkly humorous short story in Phil Klay’s debut collection, Redeployment. Klay served as a public affairs officer in the Marines during the 2007 Iraq surge before returning to school to get his MFA at Hunter College in New York City. Among other outlets, his work has appeared in the literary magazine Granta, the New York Times, Newsweek, and The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2012. Redeployment goes on sale this week.

“Bodies” follows a young Marine who returns home after a serving in Iraq as a Mortuary Affairs Specialist, and then resorts to lies and embellishment in tackling what might be the great challenge of homecoming: how to talk to civilians about what you’ve been through.

Mortuary Affairs is a particularly grim assignment, which involves finding and handling soldiers’ remains. When he tells his “funny” version, Klay’s narrator describes an “arrogant bear” of a lieutenant colonel swaggering over to help him with a body bag: “‘He was strong, I’ll give him that,’ I’d say. ‘But the bag rips on the edge of the truck’s back gate, and the skin of the hajji tears with it, a big jagged tear through the stomach. Rotting blood and fluid and organs slide out like groceries through the bottom of a wet paper bag. Human soup hits him right in the face, running down his mustache.’

“Even if it had happened, more or less, it was still total bullshit. After our deployment there wasn’t anybody, not even Corporal G, who talked about the remains that way.”

The difficulty Klay’s characters face while trying to express their Iraq experiences sits like a lump in the reader’s throat throughout the collection. But the variety of those experiences is wide, and Klay takes us to disparate corners of the armed services: from Psychological Operations to the Chaplain Corps, from the bloodthirsty and reckless to the tragicomic and absurd. I tracked Klay down to ask about his book and about his own experiences over there.

Mother Jones: How has the literary world received you, a military man?

Phil Klay: It’s a different culture. I went straight from the Marine Corps to the MFA. The way that you would express things among Marines is somewhat different than the way you’re supposed to express things in a creative-writing workshop. So there was certainly an adjustment period.

MJ: What led you to join the Corps?

PK: A ton of reasons. I was in college. I was a physical guy, a boxer and rugby player. There’s a tradition of public service in my family. I’m one of three boys that joined the military. My father was in the Peace Corps. I felt that whether or not the war was a good idea, you would still need good people executing US policy to try and make things turn out as well as they possibly could. There’s a tendency to look at anybody who joined the military as if they underwrote everything that happened policywise. That’s not really the case. I have a friend who both protested the Iraq War and joined the military, and ended up serving two deployments in Afghanistan.

MJ: Your characters have very diverse experiences and military assignments. How did you research what things were like in these various departments?

PK: As a public affairs officer, I spent a lot of time with a lot of different types of units. The variety of experience is broad, so I did as much research as I could. I wanted to get the details right, and be true to the experience, but at the end of the day I didn’t want the reader to just accept everybody’s story at face value.

MJ: In one story, “Unless It’s a Sucking Chest Wound,” your narrator, an adjutant, tears up when he nails the write-up for a hero’s award application. His account is factually accurate, but he never even met the guy he’s writing about. So there’s an element of fictionalization there. Do you think the fictional form actually makes it easier to tell true stories from the war?

PK: I think so. I think it allows you a certain distance and a certain freedom, because you’re dealing with really hard subjects. You want to respect what people have been through. With fiction you can take something that bothers you, or that you don’t have in clear focus, and you can put it under as much stress as you want. Really get underneath the skin. With nonfiction you’re restricted to what happened.

MJ: A friend of mine served in Iraq, and she’s never really told me any stories about it. She has PTSD, and I didn’t wanted to push her. But the other day I overheard her telling a person she’d just met about some serious shit. And it occurred to me that talking with someone you don’t really know about this stuff might be easier.

PK: Yes. Of course. It’s very difficult to allow yourself to be vulnerable enough to talk about certain things. This isn’t just about the veteran experience. This is with any aspect of life. With a stranger there’s less at stake. You don’t run the risk of altering a relationship that is valuable to you or that is comfortable in some way.

MJ: I see some Richard Yates in your stories. Many of his male protagonists were World War II vets who returned home with less-than-heroic status. And you see how they tried to manipulate the popular civilian narratives about the war, and how hard it was for them to convey the reality of their experience.

PK: I love Yates. It’s funny, you’re the only person to ever ask me about Yates. Revolutionary Road is an amazing book. The main character is a vet. And there’s this scene where he’s talking to his wife about marching and feeling fully alive and present, and she’s like, “I only felt that way once, and it was the first time I met you.” For them it’s this romantic moment, except that it’s written with this ironic distance. These are people who are telling themselves stories that they want to believe in. There’s no unmediated relationship to reality, right? You go to war with all the stories and cultural baggage that you bring with you, and then you bring a lot of it back.

MJ: Redeployment isn’t as overtly political as some other recent books about the Iraq War.

PK: I’m not consciously avoiding politics, and I didn’t think that I avoided politics. I have very complicated feelings about the war. There was a lot of wishful thinking. You want to talk about narratives that don’t correspond to reality. There was a lot of willful blindness. It’s not so much a pro- or anti-war stance as a question of competence. I saw Donald Rumsfeld selling a book of leadership tips on Meet the Press and the Today Show, and I was like, “How is this possible?” I understand why anti-war folk don’t like Rumsfeld, but if you were pro-war you really shouldn’t like him, because he messed it up and invalidated your whole worldview. You should be concerned about the untold thousands of dead Iraqis and Afghans. All because of somebody being an incompetent secretary of defense. He refused to acknowledge what was happening, and presided over gross waste, fraud, and abuse—and Abu Ghraib. That’s objectively a bad legacy. Are we really taking this seriously? Or is politics like sports teams: Even if they suck, they’re your team.