"With Wind," an installation at Ai Weiwei's Alcatraz exhibitionShane Bauer

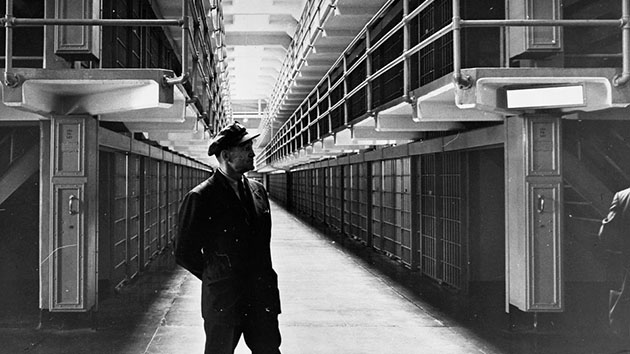

There is a question that every prisoner ponders once the realization sets in that his freedom is gone: Can the mind be liberated when the body is not? It’s been a while since I’ve asked myself such a thing—I was released from an Iranian prison three years ago—but a Chinese dragon in a former prison factory at Alcatraz makes me think about it again. Its multicolored face is baring its teeth at me when I enter the cavernous room. In this space, prisoners washed military uniforms during World War II.

The dragon is the first of many installations in the art exhibition by Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, called @Large. The beast is a startling greeter—its whiskers are paper flames—but the impression softens as I look closer. The long body, shaped like a traditional Chinese dragon kite and suspended by strings from the ceiling, snakes gracefully throughout the open factory floor, illuminated by the soft afternoon light spilling in through a multitude of little windows. Bird-shaped kites are suspended throughout the room. It is quiet. This prison room feels like freedom.

There is more to it. Every segment of the dragon’s long body is painted with flowers from countries that seriously restrict the civil liberties of their citizens, such as Saudi Arabia and Ethiopia. Other parts of the dragon are adorned with quotes by prominent dissidents. One is from Ai Weiwei himself: “Every one of us is a potential convict.”

That’s something this man surely never forgets. The themes of Ai Weiwei’s art have not been popular with the Chinese authorities. In 2011, he was arrested for alleged tax crimes and held for 81 days without charge. He hasn’t been allowed to leave China since. There are cameras mounted outside his studio in Beijing, to monitor him.

Ai directed the layout of the exhibition through video conferences with Cheryl Haines, director of the San Francisco based For-Site foundation, who initially came up with the idea of an exhibition designed specifically for Alcatraz. After she got Ai to agree, the National Park Service, which manages the island, decided to consult with the State Department. “Having a prominent Chinese dissident set up such a large exhibition was politically sensitive,” Marnie Burke de Guzman, For-Site’s Special Projects Director, told me—though State officials readily approved the project. They knew the exhibition would deal with themes of freedom, captivity, and human rights. What they did not know is that the United States would be among the many countries Ai would call out for cracking down on dissidents.

In @Large, Ai gives us the opportunity to reflect on the psychological differences between the watcher and the watched. From the dragon room, a side door leads up a set of clanky metal stairs that open onto the “gun gallery,” a long narrow hallway that guards once walked to monitor the inmates on the shop floor below. From the guards’ vantage point, the dragon that was so graceful and beautiful up close looks like a caged, threatening beast. The flowers and quotes on his body appear muted through the cracked, foggy windows. My attention is constantly drawn back to the most dangerous aspect—his wild, burning head.

Walking down the gallery, I catch glimpses of “Refraction,” a gloomy, five-ton structure that gives the impression of a giant bird wing. I cannot get up close: The only way to view the piece is through the cracked windows of the gun gallery. The installation obliquely references Tibet: Its “feathers” are made of reflective panels originally used in Tibetan solar cookers. Whomever we are to imagine confining it did not find it necessary to imprison the giant bird itself, only the appendage that gives the animal its freedom.

One installation, “Trace,” has 176 portraits laid out in a field of Lego bricks. Each image is the colorful, pixelated likeness of someone who has been imprisoned or exiled because of their beliefs, political actions, or affiliations. There are more faces from China than any other country. Among them is Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, named the 11th Panchen Lama by the Dalai Lama. After his selection at age six in 1995, he was detained by Chinese authorities and hasn’t been seen since. Scattered among the Iranian, Bahraini, and Vietnamese faces are a few American ones: Martin Luther King Jr., Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning. There is John Kiriakou, currently in prison for disclosing the name of a covert CIA officer who engaged in brutal Bush-era interrogation programs.

There is also Shakir Hamoodi, an Iraqi American imprisoned for violating sanctions by sending money to family and friends in Iraq during the Saddam Hussein era. He was convicted in 2012, nine years after Saddam’s fall. One of the largest faces is that of Shaker Aamer, a detainee who has been cleared for release by both the Bush and Obama administrations, but remains at Guantanamo 12 years after his arrest, still without charge or trial.

The large number of faces and names in “Trace” make it difficult to connect to each person, but in Alcatraz’s mess hall, there are people sitting at tables and writing messages to political prisoners. This installation, “Yours Truly,” offers free postcards decorated with national birds and flowers, each addressed to a specific prisoner. Ai understands that a prisoner’s greatest fear is being forgotten, and given that many of these postcards will certainly be intercepted before they arrive, the project may be intended to remind prison authorities that people are watching.

Alcatraz is an appropriate place for an exhibition about political imprisonment. While the island’s tourism literature focuses on hard-core criminals like Al Capone and the Birdman, it has also held hundreds of nonviolent political prisoners. Hutterite pacifists were put in solitary confinement here for refusing to serve in the military in 1918. World War I conscientious objector and anarchist Philip Grosser spent part of his year and a half on the island in “The Dungeon” where he subsisted on bread and water in complete darkness. Jackson Leonard was sent to Alcatraz in 1919 after distributing Industrial Workers of the World literature on an Army base. World War II veteran Robert George Thompson did time there in the early 1950s after joining the Communist Party USA.

This part of the island’s history is indirectly referenced in @Large. In the prison psych ward, opened exclusively for the exhibition, visitors can enter two “psychiatric observation cells,” small rooms lined with clinical looking green tiles where the mentally ill were kept in total isolation. There is nothing to see; the only thing to do is stand and listen to the traditional chants playing through hidden speakers. One is a Hopi song, a reminder of the 19 Hopis imprisoned here in 1895 for opposing the forced education of their children in government boarding schools.

The cells feel like an artifact of a bygone era, but prisons and jails around the country still routinely place the severely mentally ill in solitary cells, where they can languish for months or years. “It’s hard to imagine not going crazy in a room like that,” one of the @Large guides comments to me.

Down the hall is the “Blossom” installation. Thousands of tiny ceramic flowers, drained of color, evoke China’s Hundred Flowers campaign. In 1956, dissidents were crushed after a brief period of tolerance, banished to oblivion like these white heaps of flowers filling the sinks, bathtubs, and toilets of the psych ward.

There is one section of the prison the National Park Service did not initially offer Ai for his exhibition—the cell block. But he insisted on access, and NPS agreed.

Visitors enter the tiny cells—I can’t even fully extend my arms between the walls—and sit on a single metal stool at the center. In each one, I hear the music or poetry of dissident artists past or present. There is the screaming punk rock of Pussy Riot—”Virgin Mary, Mother of God, become a feminist, become a feminist, become a feminist!” There is the voice of Martin Luther King Jr. giving his “Beyond Vietnam” speech. There is Fela Kuti and Czech poets and singers from Tibet and Robben Island.

I sit in one of the cells and listen to the words of Ahmad Shamlu, an Iranian poet imprisoned by the Shah.

They sniff at your heart—

These are strange times, my dear

—and they flog love

By the side of the road by the barrier

Love must be hidden at home in the closet

In the background I can hear a guard shouting, clanging the cell doors shut repeatedly to show the tourists what it might sound like, had they been imprisoned here. Sitting in the tiny cell, facing the wall, it is not hard to imagine that the clamor is real. Looking at the vent, where the mournful poet’s voice comes in, it is not hard to imagine he is a neighbor, whispering to me secretly.