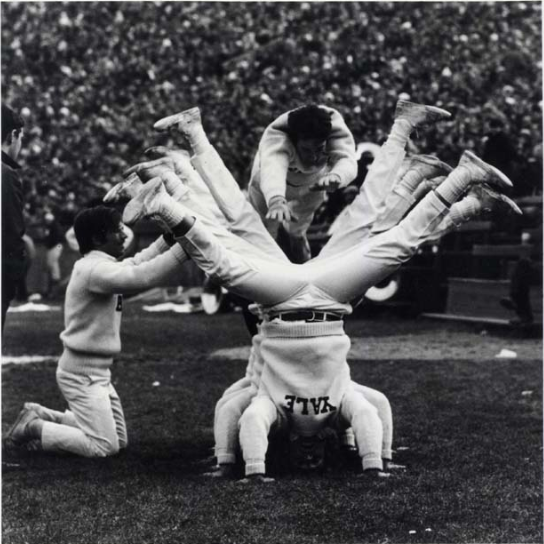

Robin Williams cheers with the Denver Broncos cheerleaders for a Mork and Mindy episode in 1979.AP

Not all is sunny and chipper in the world of professional cheerleading this year. NFL cheerleaders from five squads sued their teams last spring, alleging sub-minimum-wage pay, mandatory “jiggle tests,” and other degrading working conditions. Since then, some NHL “ice girls“—hockey’s cheerleaders—have spoken up with similar complaints. All this got me wondering: How did we get here?

Cheerleading today is nearly unrecognizable from cheerleading a century ago, when it emerged as an elite activity for men at Ivy League schools, led by “rooter kings” and “yell leaders.” Since then, it has morphed with the social movements of the time: Women took over when the men went to fight in World War II; riots erupted when people of color weren’t chosen for teams at newly integrated schools; the feminists of the ’70s denounced the hypersexualized activity that pro cheerleading had become. Internal tensions have bubbled up too, particularly as competitive cheerleading has evolved to look like acrobatics or gymnastics, while pro cheerleading has transformed into something between modeling and dancing. And cheerleading continues to evolve and broaden in scope; America’s more than 3 million cheerleaders include elementary schoolers, senior citizens, jeerleaders, and queerleaders.

So, how exactly did we get here? Check out the timeline below.

Late 1800s: The first intercollegiate football game is played between Princeton and Rutgers in 1869. By the early 1900s, football is the most popular college sport, and male “yell teams”—groups of elite students, primarily at Ivy League schools—start to form.

1909: In an article about the annual Yale-Princeton football game, a New York Times article reads, “Strangers who see hatless and coatless youths making amazing gestures on the lawn in front of the big pavilion need not tremble for their safety. For the arm-waving, head-bobbing young men will be not maniacs, but cheerleaders.”

1911: Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell describes cheerleading as “the worst means of expressing emotion ever invented.” In response, The Nation defends the activity: “The reputation of having been a valiant ‘cheer-leader’ is one of the most valuable things a boy can take away from college. As a title to promotion in professional or public life, it ranks hardly second to that of being a quarterback.”

1924: Stanford introduces cheerleading to its curriculum. According to a New York Times article: “There will be classes in Bleacher Psychology, Correct Use of the Voice, and Development of Stage Presence. Credit will be given to sophomores trying out for the position of yell-leader.”

1940: More than 30,000 high schools and colleges have cheerleading teams. While men serve in World War II, women start to take over cheerleading.

1948: A former cheerleader named Lawrence Herkimer runs the first cheerleading camp. Fifty-two girls and one boy attend; the following year, 350 students participate. In 1952, Herkimer borrows $200 to start making crepe-paper pom-poms in his garage. He would go on to patent the invention in 1971.

Lawrence Herkimer at an early cheerleading camp Varsity Spirit

1955: The Catholic Youth Organization holds its first annual cheerleading competition for elementary, middle, and high school girls in New York. By 1961, the competition would host 1,500 girls.

Early 1960s: A wave of NFL teams introduce cheerleading squads. By 1970, 11 teams will have squads, including the Atlanta Falcons’ Falconettes, the Dallas Cowboys’ Cowbelles and Beaux, the Kansas City Chiefs’ Chiefettes, and the Washington Redskins’ Redskinettes. Some teams now have alumni associations documenting the group’s history. Below, a screenshot of the Washington cheerleaders alumni website, including a photo of the 1962 Redskinettes.

1965: Radcliffe women cheer on the AFL’s Boston Patriots at Fenway Park. The Associated Press notes, “The girls’ lineup looks a bit ragged too but Radcliffe doesn’t teach cheerleading.”

1965: Yale bars women from cheerleading. The director of college athletics explains that the ban isn’t because he’s against female cheerleaders, but because cheerleading is an activity for current undergraduate students. The university wouldn’t admit its first women until 1969.

1966: Congressional staffers who work for Democratic politicians cheer before the 1966 Roll Call Congressional Baseball Game:

1967: Seventeen football players at Madison High School in Illinois are barred from the team for boycotting a practice after only one black cheerleader is picked for the varsity squad. Following the dismissal of the football players, nearly all of the the school district’s 1,300 black students boycott classes for a week. As schools continue to integrate, one factor adding to tension is the difference in cheerleading styles between black and white schools: As Lou Lillard, a black cheerleader named All-American in 1972, explained, “The type of cheering at black high schools is…more of a stomp-clap, soul-swing…At [white] schools, the traditional cheers are straight-arm motions.”

1967: Pop Warner, a youth football league, introduces cheer and dance programs for elementary and middle-schoolers, opening up the sport to cheerleaders as young as four years old. The programs have grown over the years; below, a photo from a recent Pop Warner competition:

1968: Two weeks after John Carlos and Tommie Smith’s iconic medal stand demonstration at the Summer Olympics in Mexico City, Yale cheerleaders Greg Parker and Bill Brown give Black Power salutes during the National Anthem before a game against Dartmouth.

1969: As integration spreads at Southern schools, some black cheerleaders refuse to dance to “Dixie” or wave the Confederate flag. Violence erupts in Burlington, North Carolina, after recently integrated Walter Williams High School fails to select any black cheerleaders. The governor declares a state of emergency and a curfew, and 400 National Guard troops arrive to quell riots. A black 15-year-old student named Leon Mebane is killed.

1969: More than half of the 2,800 students in Texas’ Crystal City public school system stage a monthlong walkout after only one Mexican American cheerleader is picked by the majority white faculty in a city that is 85 percent Mexican American.

Early 1970s: As the Women’s Liberation movement gains steam, doubts about cheerleading emerge; a 1972 New York Times article about a cheerleading competition reads, “The rah-rah world of cheerleading had no room on the squad for Gloria Steinem, Germaine Greer and other Women’s Lib killjoys.”

1971: Hundreds of black students at New Brunswick High School in New Jersey boycott classes after a black girl is dismissed from the cheerleading squad.

1972: Title IX, the landmark gender equity law, passes. The same year, Dallas Cowboys owner Tex Schramm decides that he wants cheerleaders to be more entertaining, and, as the team’s website puts it, “He knew that the public liked pretty girls.” He hires choreographer Texie Waterman in 1972 and, soon after, director Suzanne Mitchell. Under their lead, cheerleading becomes a tantalizing dance: Women perform choreographed routines in short shorts and midriff-bearing uniforms. The team implements rules that quickly become the norm for pro cheerleaders: no fraternizing with players, no wearing the uniform outside of team-sponsored events, no weight fluctuations. Cheerleaders are to be alluring, yet pure; as Mitchell told me, “We wanted everyone to look at them and say, ‘Now they are ladies.’

1974: Two years after the passage of Title IX, some worry that female cheerleaders will leave for other sports. Jeff Webb, a former college cheerleader who advocated for incorporating more gymnastics into the activity, founds the Universal Cheerleaders Association. The organization would go on to hold hundreds of competitions, clinics, and camps, with a focus on acrobatic stunts and pyramids. Below, a photo of the UCA staff in the 1970s:

1975: Some 500,000 students are participating in cheerleading, from elementary school to college. An estimated 95 percent are female.

1976: The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders draw attention from around the country when they perform at the Super Bowl, debuting their new uniforms on a national stage.

1977: The Cowboys cheerleaders make the cover of Esquire. Cover line: “The Dallas Cowgirls (The Best Thing About the Dallas Cowboys).” A record 475 women show up to compete for 35 spots on the team; the following year, 1,000 women will try out. A New York Times article details what candidates have in store: “Stringent conditioning and diet control, rehearsals four or even five nights a week, five hours a night. Miss two rehearsals and you’re off the squad forever…Because of the strong Christian ethic that infuses the Cowboys program…the cheerleaders cannot appear where alcohol is served, cannot attend parties of any sort, cannot even wear jewelry with their brief costumes.” Successful candidates earn $14.72 per game after taxes and aren’t paid for practice. Feminist groups denounce the team as sexist; the New York Times writes, “With their short shorts, crop top, vest and white boots, the Cowboy cheerleaders hardly resemble the spirited State U. coeds of the past in long skirts and bobby socks.”

1977: Other pro cheerleading squads follow in the footsteps of the Cowboys cheerleaders, incorporating crop tops and short shorts into their uniforms and suggestive dance moves into their routines. Among the first to make this shift are the Los Angeles Rams’ Embraceable Ewes, the Buffalo Bills’ Jills, and the Chicago Bears’ Honey Bears. The Washington Post declares, “Their disco dancing, skimpy costumes and sultry looks have become the prototype of the new cheerleader.” (The Post‘s coverage of the NBA’s Washington Bullettes: “There they are, in their high-cut red hotpants and red wedgies, Farrah Fawcett manes tossing, dancing on the Capital Centre’s basketball court to the tune of the “Bullets loaded with hustle” songs, smiling as though they were queens for a day.”)

1978: A member of the San Diego Chargettes is fired after modeling for Playboy. According to a Washington Post article: “Morally outraged, Playboy came to the defense of the Chargettes, issuing a press release that said, in part: ‘The Chargers—and other teams—have wrapped these enthusiastic young ladies up like candy every weekend on national television. All we did is ask them to remove the wrapping.’ Presumably, the unwrapping of the Chargette did not expose a Baby Ruth, or even a Snickers. We will find out when we do our serious reading in November.” A writer from the Chicago Tribune laments, “Ten years ago, the entire brigade of National Football League cheerleaders was 17 housewives burdened by cellulite who chewed two sticks of Doublemint at a time, had husbands who worked on oil rigs, and lived in a trailer park in Grand Prairie, Tex. Now there are a whole mess of cheerleaders from other places, like Chicago and Los Angeles and Denver and New Orleans, wearing no clothes and smiling at you from the slick pages of the December issue of Playboy magazine.”

1979: The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders Inc. sues Pussycat Cinemas Ltd. for trademark infringement in the porn movie Debbie Does Dallas. In it, the lead character, dressed in a uniform nearly identical to that of the Cowboys cheerleaders, exchanges sex for money in order to save up to travel to Dallas to try out for the “Texas Cowgirls.” The group is prohibited from distributing the film, but still goes on to sell 50,000 copies. The movie spawned later remakes and sequels, including Debbie Does Wall Street (1991), Debbie Does New Orleans (2000), Debbie Does Dallas: The Musical (2002), and Debbie Does Dallas…Again (2007).

1979: The Sun City Poms, an Arizona-based squad for women older than 55, forms to cheer on the Sun City Saints women’s softball team. Today, the group performs up to 50 shows a year at parades, pep rallies, and other events. Below, the Poms in the ’80s:

1979: Robin Williams joins the Denver Broncos’ Pony Express to film an episode of Mork and Mindy. (See photo above.)

1979: The US Department of Defense requests the presence of the Cowboys cheerleaders during a tour of installations in Korea, starting a tradition of pro cheerleading squads performing at military outposts around the world. Since 1979, the Cowboys cheerleaders have collaborated with United Service Organizations (USO) to perform more than 75 times at foreign military bases.

1979: The Laker Girls are formed, after Lakers owner Jerry Buss decides that he wants spice up the atmosphere at NBA games. Paula Abdul is an early member, and quickly becomes the group’s head choreographer. Today, every NBA team has a dance squad. Below, a Laker Girls performance in 2006:

1980: The Universal Cheerleaders Association holds the first National High School Cheerleading Championship at SeaWorld. Three years later, ESPN begins broadcasting the event. Below, a clip from the 1987 championship:

1984: At least 150,000 American girls are participating in cheerleading clinics each year. Lawrence Herkimer, owner of the National Cheerleaders Association, laments the transformation of professional cheerleaders to a New York Times reporter: “There’s a little mixture between go-go girls and cheerleaders. You don’t see that scantily clad kind of thing in high school.” Two years later, Herkimer would sell his cheerleading empire—composed of organizations running cheerleading camps, clinics, and supply stores—for $20 million.

1993: A Texas school reverses its decision to ban pregnant girls from the cheerleading team after the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Organization for Women threaten a lawsuit. Four of the school’s 15 cheerleaders had become pregnant; one who had an abortion was let back on the team.

1995: American Cheerleader magazine publishes its first issue. Below, the magazine’s latest cover:

1995: The Buffalo Jills form a short-lived union called the National Football League Cheerleaders Association. The union, the first of its kind, aims to raise pay for cheerleaders and give squad members more say over their uniforms and public appearances. At the time, the Jills weren’t paid for practice or travel—they even flew themselves to the Super Bowl. Within a few months, the Jills file a grievance to the National Labor Relations Board alleging that the team had canceled many of their public appearances and didn’t notify veterans about tryouts. Just a year later, the union is forced to dissolve after the Bills find a new sponsor for the team.

1996: Pro cheerleading teams continue to perform at military outposts. Below: A San Francisco 49ers cheerleader performs for Fourth of July celebrations at Camp McGovern, near Tuzla, Bosnia.

1997: As the Raleigh, North Carolina, News & Observer puts it, “Barbie is finally going to college and, of course, she’s going to be a cheerleader.” Nineteen different college cheerleading uniforms are available for the ultraflexible doll: Auburn, Arizona, Arkansas, Clemson, Duke, Florida, Georgia, Georgetown, Illinois, Miami, Michigan, Nebraska, North Carolina State, Oklahoma State, Penn State, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

2000: The feature film Bring It On comes out; the movie’s plot was inspired by a Universal Cheerleaders Association high school competition.

2006: Two cheerleader reality TV shows debut: Lifetime’s Cheerleader Nation follows Dunbar High School cheerleaders in Lexington, Kentucky, as they make their way to nationals. Making the Team, on the Country Music Channel, follows Cowboys cheerleader hopefuls through tryouts. The former lasted only one season, while the latter is still airing today. Below, a clip from the latest season of Making the Team:

2012: Fifteen high school cheerleaders and their parents sue the Kountze Independent School District in Texas after the district banned the cheerleaders from displaying banners with Bible verses on them. Republicans Rick Perry and Ted Cruz express their support for the cheerleaders.

2014: In January, a former Oakland Raiderette named Lacy T. files a class action lawsuit against the Raiders for, among other things, failing to pay cheerleaders for the hours they work. By May, members of four other squads will have followed suit: the Cincinnati Bengals’ Ben-Gals, the New York Jets’ Flight Crew, the Buffalo Bills’ Jills, and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers cheerleading team. The lawsuits allege a variety of indignities: Cheerleaders don’t earn minimum wage, aren’t paid for practice, are fined for minor infractions (e.g., bringing the wrong pom-poms to practice), are forced to pay for expensive beauty regimens, and are subject to body-policing off the field. In September, the Raiders agree to pay $1.25 million to settle Lacy T.’s suit.