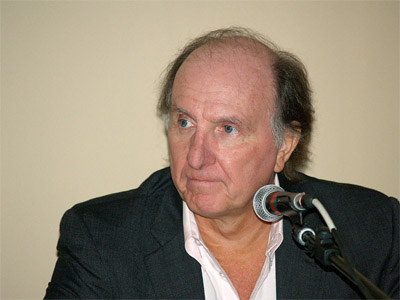

Globe Photos/Zuma

He must have been exhausted. We have all been exhausted, watching America shout down common sense and set ablaze the last few defensible vestiges of circa-1787 political and economic philosophy. But as much as it all weighed on many of us, he carried extra baggage. He had literally written the book on Donald J. Trump’s bent psyche and business. He had forgotten more dirt on Trump than reporters of my generation ever dug up.

But Wayne Barrett, a longtime Village Voice investigative political reporter and mentor to hundreds of journalists, wasn’t tired. He wanted to work, man; and work he did, even as he was driven away to the hospital for the last time, dying there at 71 late Thursday. Wayne needed all the time allotted to him, because America needed him.

On the drive to the hospital where he breathed his last, Wayne Barrett was still doing interviews for a big, tough story on Donald Trump.

— Tom Robbins (@tommy_robb) January 20, 2017

When it became clear a year ago that Trump actually might ascend to lead the nation’s oldest political party, Wayne’s 1992 investigative biography, Trump: The Deals and the Downfall, got a reprint—and an instant audience among other journalists. Based on digging Wayne had done since the ’70s, it’s the keel on which a great deal of the best Trump reporting was built.

Trump was only one of the big whales Wayne hunted, though. He wrote two books on Rudy Giuliani, scorching his largely bogus 9/11 heroism, along with his relationship-wrecking and influence-peddling. In 37 years at the Voice, and recently in other fair corners of the internet, Wayne put the screws to Ed Koch, Al D’Amato, Mike Bloomberg, and multiple Cuomos.

Over the past 18 months, Wayne fielded a steady stream of calls and emails. Reporters asked for help with a distant mob name, a defunct company, a disgruntled counterparty. “I got some stuff on it in the basement,” he told me on the phone last year when I ran a very specific bit of ’80s Trump trivia past him. “Come on up and dig.”

Lots of reporters took him up on similar offers, a steady queue of them making the pilgrimage to the Brooklyn house he shared with his wife, Fran, to chitchat and sift boxes on boxes of notes and clippings downstairs. He was there for all of us, even if it the scheduling occasionally had to be done by one of his research interns.

Ah, the interns. Wayne maintained an army of them to dig through databases, cajole sources, connect dots, and frequently co-author pieces with him. Like the paper’s size, the Voice‘s office space shrank over the years, and six of us at a time might pile into Wayne’s cube for a quick confab. I once tried to spread out into the mostly empty next-door cubicle, which worked fine for a week until Nat Hentoff ambled in and cussed me out for a good three minutes, yelling to have his goddamn desk back.

The interns of Barrett Nation. You know them, even if you don’t realize it. They shape Rolling Stone, The New Yorker, Politico, ABC News, every major New York paper, and certainly this magazine, as my former colleague Gavin Aronsen and I have written. We are not all journalists now, and those of us in the profession aren’t all investigative reporters—one of my cohort is a book reviewer of some note and another is a fast-paced entertainment reporter, but goddamn, if you are hiding dirt, they will find it.

I loved Wayne, even when he was screaming at me, a rite of passage any of his interns can describe. He pursued truth and exposed sin with the zeal of a young Jesuit, which was fitting, since he’d considered taking up the cloth before a debate scholarship sent him to St. Joe’s College in Philly. I’d had a similar upbringing, joining the military instead of the church, debating in school, and seeking an outlet for my inflamed sense of justice.

Wayne had that fire, and lighting up other people was how it manifested sometimes. We were in a serious business. We had to be thorough, accurate, fair—even when we were breaking shit.

But it was all to an end. If Wayne burned for justice, he practiced it, too, singing his protégés’ praises to recruiters, offering a crash weekend at his beach place down the shore in Jersey, taking a sincere interest in his charges’ spouses, children, money, and family issues. “He was a family man” is often a hollow note in these kinds of tributes. But family—his and everybody else’s—truly was Wayne’s greatest pleasure, and the reason he couldn’t not needle the greedy who screwed the rest of us.

For more than a year, we watched Republicans slouching toward Trump Tower, saying that yes, seriously, they believed this debauched tycoon with a rambling sales script and an unadulterated id could handle the nukes. We saw Russia tossing gasoline on the fire, beheld our media colleagues collapsing under the weight of takes and think pieces on how maybe facts don’t matter. Now we watch the Queens-bred Caligula begin to rip up the things that make America an idea worth defending. And Wayne’s illness, exacerbated by his all-consuming work, has chosen this moment to take him from us.

We are allowed to be exhausted and dispirited and fearful. This has all really happened, and the ineptitude and malice of the incoming administration will cost lives and livelihoods. But we are not allowed to stop. Wayne wouldn’t let us.

I worked for Wayne when Rudy Giuliani was making his last serious stab at a presidential bid, and we spent a lot of time running down new stories on the candidate. His campaign had looked formidable early on, but hizzoner flamed out spectacularly and retreated into private consulting.

Was it bittersweet, I asked Wayne? His white whale, the subject of years of his life’s work, was finished and never coming back.

Wayne laughed. It was the laugh of a man who wasn’t about to retire from the truth-digging, shit-kicking business, no matter how good or bad it might get. “He’ll come back, man,” he said. “These guys always come back.”

The fun part, Wayne said, was that the good guys came back, too.