Before he quit acting to write movies full-time, Jason Hall landed a variety of bit parts, including a recurring one as the singer of a band called Dingoes Ate My Baby in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. But his most memorable role, he says, was his portrayal, for a student film project at the University of Southern California, of a Marine struggling to cope with the loss of one of his men during a training exercise. “Nobody ever saw it,” Hall says. “But that was my entry into this world, in a weird way.”

He’s talking about the world of soldiers who have returned home and are struggling to come to terms with the things they’ve seen and heard and done overseas. Hall went on to earn an Oscar nomination for his adapted screenplay for American Sniper, Clint Eastwood’s biopic of the legendary Navy SEAL Chris Kyle.

Hall’s latest film, and his first as director, is a powerful adaptation of David Finkel’s nonfiction book Thank You For Your Service. Out October 27, the film stars, among others, Miles Teller, Haley Bennett, and talented newcomer Beulah Koale. It follows a group of soldiers (and their loved ones) as they struggle with the aftermath of their tours in Iraq.

The soldiers portrayed in the film are real, and screening his film for them was “intense,” Hall told me. “Even if these guys had the words,” he says, “they cannot tell you what war is like—the texture and the relationships and the brotherhood and the bravery and the fear and the trauma. You can’t explain that over a beer. You can’t explain that to your wife or to your kids. The effort with the film was to explain the inexplicable.”

Sgt. Adam Schumann (Miles Teller) on patrol in Iraq.

Francois Duhamel/Universal Pictures

Mother Jones: Okay, first things first: Buffy the Vampire Slayer?

Jason Hall: [Laughs.] It paid my rent for a while, and Joss Whedon said I was perhaps the best lip-syncher he’d ever worked with—which I think is why he had me back.

MJ: How did you go from playing bit parts to writing big films?

JH: I was into the acting, but it was hard to get auditions for movies. I’d read the scripts and I’d be like, “God, this is terrible!” I always had written, so I set out to write a movie slightly better than the terrible movies I was reading. I turned over a couple of scripts. It was always my acting that seemed to kill the project. I turned down Miloš Forman to direct a movie because he didn’t want me to be in it. I said, “Miloš Forman can fuck off!”

MJ: Do you regret that?

JH: Well, yeah. I did it again with John Dahl, who was like, “Hey, what if Matt Damon wanted to play this wrestler?” I was like, “Matt Damon can fuck off!”

MJ: You were a wrestler yourself.

JH: That’s right. I ended up finally giving over a movie: The now famous David Mackenzie directed Spread, with Ashton Kutcher, and it was a total disaster. But after that I started allowing myself to just be a writer.

MJ: It must be hard to turn your script over to a director who might not share your vision. Was it a relief to direct your own work?

JH: Yeah. And then it’s a tremendous responsibility because you have to translate what you imagined. As a writer you translate it to the director. As the director, you translate it to your production designer, who translates it to the props department and to everybody else.

The boys head home: Schumann, Solo (Beulah Koale), and Will Waller (Joe Cole).

Francois Duhamel/Universal Pictures

MJ: How did you put yourself in the director’s chair?

JH: I had a good relationship with Steven Spielberg, who was directing American Sniper for a period. He ended up dropping out, but he learned to trust me. In the middle of that process, he handed me [Finkel’s] book, and said he wanted to direct this. I started writing it for him. When I found out he wasn’t intending to direct, it was up to me to convince him to let me do it.

MJ: Did you put your soldier-actors through some kind of boot camp?

JH: Yeah. We had a master chief from Seal Team Six. He ran this executive, ass-whipping boot camp for many years. He was a growler—the most intense individual you’ve ever been around. He makes Viggo Mortensen look like someone’s nanny.

MJ: Wasn’t this supposed to be boot camp lite?

JH: Nothing lite about it. The first day, I got there at almost 3 a.m. and they were salamander-crawling across cement. All of them were in a daze.

MJ: Did the actors know what they’d signed up for?

JH: They had no idea! They never slept more than two to three hours and they were put through actions and exercises that tested them in every way. It was traumatic. When I got there at the end, they were like, “Did you know what they were going to do to us? This is illegal, man!” But what I saw is five guys who had each other’s backs. They’d used each other’s bodies to stay warm at night. They knew the sounds, the smell, and feel of each other. It brought them together in a way that showed up on camera.

Saskia Schumann (Haley Bennett) awaits her husband’s flight.

Francois Duhamel/Universal Pictures

MJ: Do you have friends or family who served?

JH: My stepbrother went away to Desert Storm. My grandpa flew bombers in World War II and my uncle was in Vietnam. My dad always said his biggest regret was not signing up to go to war in Vietnam. In his later years, he felt like that made him a coward.

MJ: Were you ever inclined to enlist?

JH: No. I was far too selfish or artistically inclined to even think about it.

MJ: I read that Chris Kyle, the subject of American Sniper, took his time warming up to you. Tell me about your first meeting.

JH: I met him just a few months after he was out. He was entertaining about 50 Texas Rangers, cops, at a friend’s ranch. They were taking him out hunting. I was wearing a hoodie, which was a bad idea. I was probably the only guy within 100 square miles not wearing cowboy boots. And I don’t drink. It was an intimidating environment and Chris was an intimidating character. There was an air around him that was very dark. What he had done wasn’t resting well on him.

MJ: American Sniper was a big hit, but I actually found Thank You for Your Service more powerful, maybe because the characters were more relatable to me. Kyle was this macho, inscrutable cowboy type, whereas Finkel’s guys are less certain about things, better at expressing their vulnerabilities, and more willing to ask for help.

JH: When you ask a hero for the true story you’re going to get the hero’s story, but these guys had nothing to risk by telling the whole truth. David Finkel followed them in the war for 10 months and followed them home for another 13. He lived with them. What you got was a firsthand account of this war at home in a way that we’ve never seen it before.

Solo and Schumann console Waller, whose girlfriend has abandoned him.

Francois Duhamel/Universal Pictures

MJ: There are scenes, like when Sgt. Schumann’s wife takes him to the speedway, where it feels like we’re inside the guys’ heads.

JH: The vibration of those cars was accentuated by sounds of Humvees and tanks. There’s screaming. You don’t recognize it, but it’s in there. I did that in many places throughout the film. I worked a lot with the subconscious, trying to find a way to articulate the terror and the hyper-vigilance.

MJ: You also depicted a hopelessly backlogged Veterans Administration where a soldier in need of psychological help might wait six months or a year to be seen.

JH: Keep in mind that the movie took place after the surge. I showed it to Veteran’s Affairs Secretary David Shulkin, and he was like, “That’s not my VA!” And I said, “This was a common scene when these guys got back.” The truth is, it is still very bad in many places.

MJ: Comedian Amy Schumer plays Amanda Doster, the grieving widow of a platoon commander. Were you surprised she would seek out such a somber role?

JH: Yeah. But I auditioned 40 people and she was the most believable. She brought a sense of grief and frenzy to it. And she transformed herself. She went to James Doster’s funeral site. She spent a tremendous amount of time with Amanda. I appreciated her dedication—to show up and convince the widow of this soldier, “I’ve got your back. I’m gonna do this with dignity.”

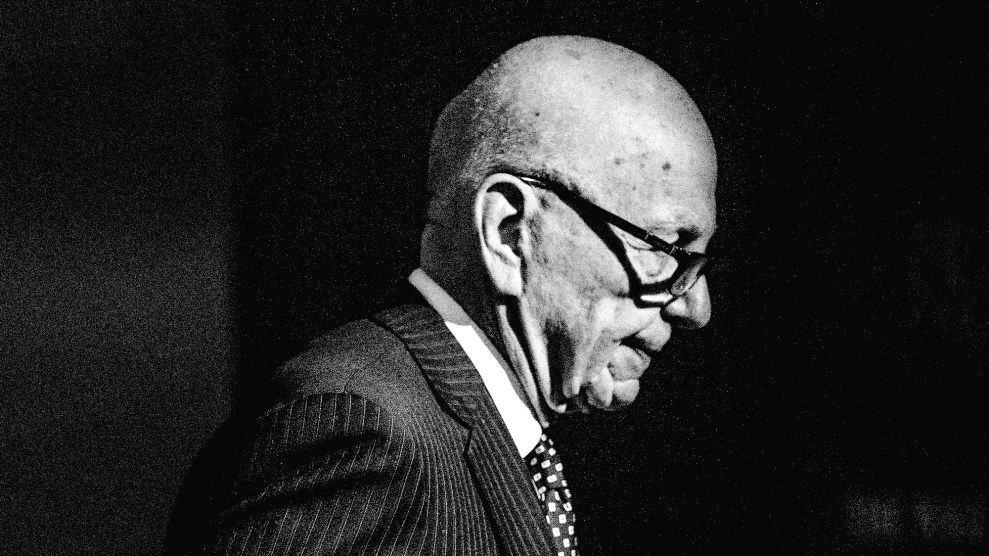

Director Jason Hall preps his actors for a battle scene.

Francois Duhamel/Universal Pictures

MJ: Amy’s character is desperate to know how her husband died, but none of the guys will tell her.

JH: They’re still trying to figure it out. To them, trauma is a series of snapshots. They’re playing back these things to figure out the point of origin. Like, “If I had gotten up that morning and tied my shoe and I’d just stopped for a second longer, would I have been the guy in that seat?” They’re wrapped up in that mystery, and I wanted to present that. The audience knows very little. We’re left to pull the threads and try and discover what happened—the source of this grief, this secret Adam Schumann is carrying.

MJ: How did the real-life veterans you portray react to the film?

JH: It was the most intense screening I think I’ll ever sit through. These moments were some of their most horrible, some of their darkest, some of their most intimate. Amanda experienced her husband’s funeral in Iraq for the first time, and you realize, “Oh, my god. This is the funeral she missed, and now we’ve brought it to life for her in this beautiful but terrible way.” They all mentioned how beautiful it was—and that we had managed to honor them. Solo said, “How did you know what my house looked like? It was like you filmed it at my house.” Of course, I had some pictures…

MJ: And he has no memory left because of his brain trauma. In the film, Solo is so desperate to self-medicate with ecstasy that he ends up in deep shit with some drug dealers. Did that really happen?

JH: There’s a level of truth. Lots of these soldiers get so frustrated with bumping up against this system that doesn’t know how to treat them. Half of the guys toss their medication because it upsets their system or it throws them into depression and fog. Or they can’t perform sexually or they lose sense of themselves. Some of them throw it out because they lose sense of the grief—and then they feel they’re not honoring the fallen.

MJ: What do you hope viewers will take away from this?

JH: This movie isn’t for the soldiers—it’s for the rest of us. My hope is that it explains what the soldiers are unable to explain. That we get to experience a little bit of what it was like, from their point of view, to walk back into this world.