Nhat V. Meyer/Mercury News/ZUMA

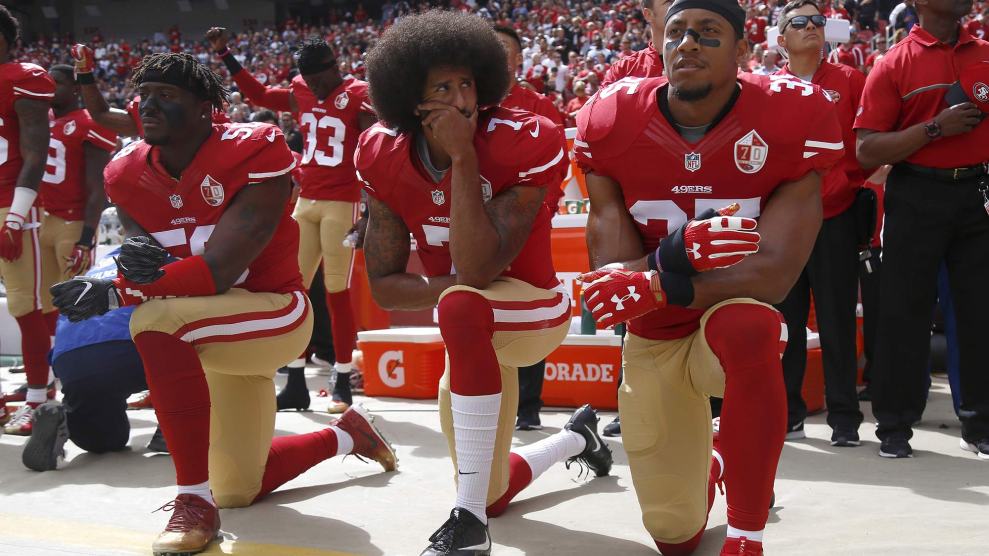

On Tuesday, 13 NFL players met with team owners in New York City to discuss how to move forward on the most high-profile issue of the 2017 season: players kneeling during the national anthem in protest of racial inequality in America—and the subsequent backlash from right-wing media and President Donald Trump. Notably absent at league headquarters was Colin Kaepernick, the former San Francisco 49ers quarterback who started the movement and who recently filed a grievance against the league, claiming owners had colluded in not signing him to a free-agent contract.

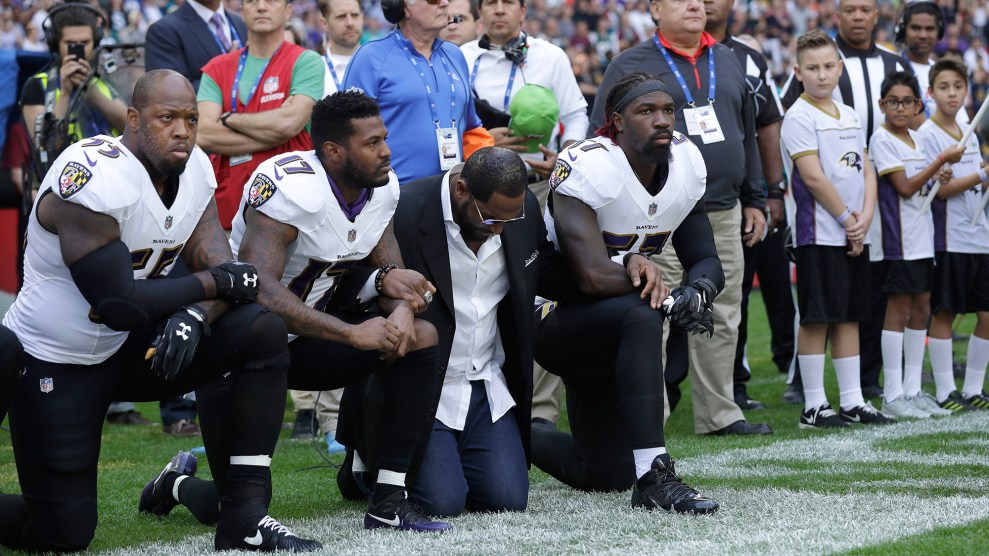

Part of Tuesday’s discussion revolved around the NFL’s role in advancing a number of social justice causes pushed by the players. But by the end of the meeting the owners decided not to make any rule changes to force players to stand during the anthem, and Trump went back on the offensive Wednesday, tweeting that the decision represented a “total disrespect for our country!”

On the other side of the country, retired University of California-Berkeley sociologist and activist Harry Edwards has been following the controversy with keen interest. Before the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, Edwards helped form the Olympic Project for Human Rights to organize African American athletes to stage a boycott over the oppression of black Americans and to “expose America’s historical exploitation of black athletes as political propaganda” at home and abroad. While the large-scale boycott never came to fruition, Edwards inspired one of the most iconic protests in international sports history, when Olympic sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised black-gloved fists from the medal stand nearly five decades ago this week.

When we spoke recently, Edwards, 74, argued that today’s athletes—thanks to both their social consciousness and ability to reach huge audiences on social media—have become leaders in the movement to end racial injustice. “If you are looking for Dr. King or Nelson Mandela today, you better look to somebody who is wearing a pair of sneakers or a pair of cleats. This is simply where we are,” said Edwards, who has lobbied for Kaepernick to be nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize and earlier this year helped establish the Institute for the Study of Sport, Society, and Social Change at his alma mater, San Jose State University.

Here’s more of what Edwards had to say about the history of protest in sports, Trump’s effect on a new generation of athletes, and the notable absence of white players kneeling on NFL sidelines.

Mother Jones: What moment in sports history would you compare this one to?

Harry Edwards: Every era has been framed up by ideological definitions and structural circumstances and dynamics that have provided the scaffolding for movements. In an era of abject Jim Crow, of American-style apartheid, from the turn of the 20th century to World War II, athletes gained their greatest recognition and respect in the international arenas. You had Jack Johnson fighting Tommy Burns in Australia for the heavyweight championship. There wasn’t a white heavyweight contender who would give him a fight.

The second wave, of course, was Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby [in baseball] and Kenny Washington and Woody Stroud in football. That struggle was not for legitimacy, as had been the case with these victories in the international arena against the system that blacks were physically, intellectually, and morally incompetent to participate in mainstream sports successfully, most certainly team sports. It’s not accidental that the sports that blacks in the international arena got their greatest respect in was all individual sports. That assault against apartheid from a team perspective, being on the fields with whites, awaited the end of World War II.

That struggle was for access, not legitimacy. We had proven that. We had proven we could compete against the world. Then in the mid- and late-1960s, that struggle wasn’t framed up by the struggle against segregation. It was framed up by the black power and ideology and movement, which meant black control, black influence, black authority, dignity, and respect. Jim Brown flat out stated, “I played football for respect.” Tommy Smith stated in an interview after leaving the Olympic Village, “It was about black dignity.” That’s why we were talking about human rights rather than civil rights.

Today, the fourth wave revolves around the exercise of power. These athletes have the money. They have the megaphone where they actually exercise power. This fourth wave is not so much in contrast of those eras. It’s in continuity with those. This wave is framed up by the Black Lives Matter movement.

Watch: The history of protest in sports, including a chat with NYU history prof Jeffrey Sammons.

MJ: How has the political climate of the era influenced how athletes have protested?

HE: With every one of these waves, you had those faces that personified the struggle and faces that personified the opposition. With Jack Johnson, you had Jim Jeffries, who was brought out of retirement to save the heavyweight boxing champion for white folks. You had Adolf Hitler, who represented Aryan superiority in opposition to Jesse Owens.

Today, you have Donald Trump, who epitomizes the opposition to such an extent that you would have a reporter [Jemele Hill] sitting at a desk at ESPN who comes out and says straight out that the president of the United States is a white supremacist, who represents everything that these athletes are protesting against. So the Trump image and the Trump era is the equivalent of those in the American mainstream who refused to fight Jack Johnson.

It’s not accidental that the Charlottesville march by neo-Nazis added fuel to what Colin Kaepernick was protesting against, what Malcolm Jenkins of the Eagles was protesting against, and added fuel to what Michael Bennett was protesting against. In every one of these eras, there’s not only an organizing ideology and a kind of movement that provided scaffolding to build on these athlete protests.

MJ: How do you think this most recent reaction to protesting during the national anthem matches up with the original intent behind Kaepernick’s initial protest, which was to call out racial injustice and police killings?

HE: Every movement throughout the history of black struggle in this country has run the risk of being co-opted, derailed, distracted. Every struggle has had to deal with that. This is no exception.

This latest thing of owners, people like Jerry Jones, who 10 days before said no protesting athlete on the Cowboys will be tolerated. After Trump sucker punches the owners and throws them under the bus, they’ve got to make a choice about whether they side with Trump and his disposition toward the neo-Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan and the white supremacists who are marching in Charlottesville or whether they side with their own players who are protesting what those groups stand for and their impact in terms of violence against African American communities in this country.

Being businessmen, they are going to lock arms with their players; some of them are going to take a knee with their players. How genuine it is depends upon what do they do from this point forward. Do they follow protest with progress, with programs? And if they don’t, what happened with Jerry Jones and [Robert] Kraft and some of those other owners represent the most craven crass display of abject hypocrisy in the history of American sports.

MJ: What do you think is the significance of kneeling as a form of protest as opposed to locking arms?

HE: It’s not about the form of protest any more than it was about the sit-ins at the lunch counters as opposed to boarding buses and riding down South in an integrated bus or whether it was about going to the polls and demanding to be registered to vote or whether it was about little black students going into a high school in Little Rock.

It wasn’t about the specific form. It’s about the authenticity of the act. It’s the fact of them speaking and what that act of protest is in reference to. For the owners, it may have been in reference to Trump throwing them under the bus. It had nothing to do with the message that Kaepernick and Michael Bennett and Malcolm Jenkins were trying to send. The fact that they are locking arms with athletes who are in fact protesting these summary executions and not having any intention of sending that message themselves makes their act an act of craven hypocrisy.

MJ: Why do you think so few white athletes have knelt?

HE: White identity overrides team camaraderie. White identity overrides team loyalty. When you look at the problem, at the very core of the police killings, it goes back to the original sin in American society. That is white supremacy.

They are reluctant to engage that core conversation. What Kaepernick and these athletes are really saying is that we need an honest conversation about race, which is an honest conversation about white supremacy in American society, which is at the core of police killings in communities of color. These white athletes are reluctant to open the door to that conversation, and unless you are Gregg Popovich, the head coach of the San Antonio Spurs, you are very reluctant to even speak about it in honest terms. We can’t have an honest conversation about race in society because we can’t have a honest conversation about white supremacy.

At the end of the conversation, the moral conclusion would have to be that we are just like other Americans, no better, no worse. These white athletes don’t want to engage in that conversation. They don’t want to go back to their communities and speak to the question of why were you siding with Colin Kaepernick and these athletes by taking a knee when the ultimate extension of that conversation is “Why are we adhering to ideological definitions of white supremacy and patriarchy in the second decade of the 21st century?” What they do is put a hand on the athlete’s shoulder: “I’m with you as a teammate but don’t ask me to engage that conversation because I have to go back home. I have to face my parents and my friends and the people at the bars and the clubs that I frequent.”

MJ: What do you make of the fact that people have forgotten that black women athletes were at the vanguard of these protests?

HE: The whole slogan and ideological scaffolding, the Black Lives Matter scaffolding of this movement, came about as a result of three black women who created the hashtag. In the wake of Trayvon Martin, it’s not accidental that Ariana Smith was the first athlete to go out and protest the Mike Brown killing in this regard long before Kaepernick spoke up, long before LeBron spoke up. It was a black woman who spoke up.

Women have a phenomenal role in this, and one of the things that I hope is that as we look at this protest movement, that we not lose sight of Aiyana Jones, that we won’t lose sight of Sandra Bland, that we won’t lose sight of these women who have died at the hands of police officers. They too have a voice and leadership role in this movement. That we won’t lose sight of the fact that Maya Moore, Tina Charles—two professional basketball players—were suspended temporarily when they spoke out about these police killings. I hope we won’t lose sight of the role of women in this and have been a vital part of this. Harriet Tubman was not an aberration. Fannie Lou Hamer was not an aberration. Angela Davis is not an aberration. We have to recognize them in this athlete movement, as well.