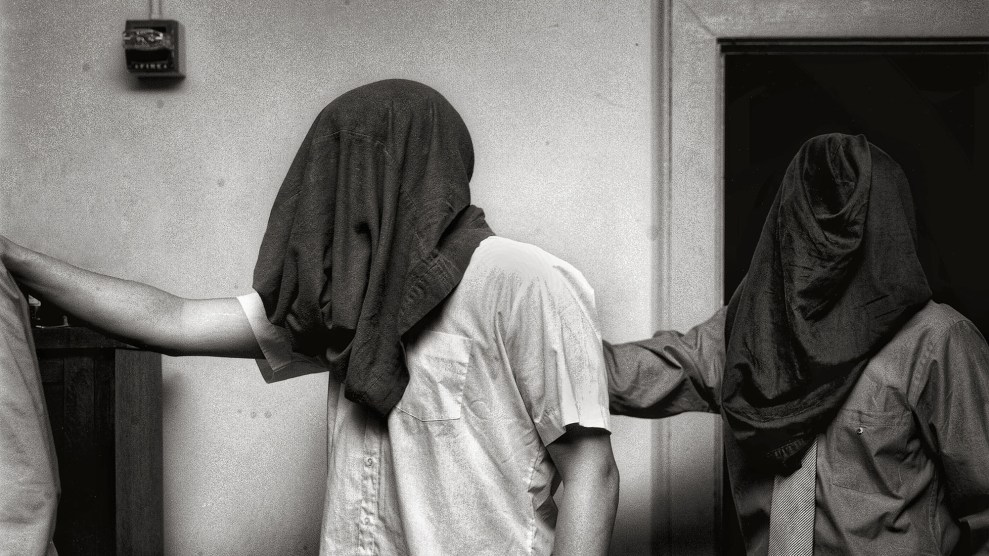

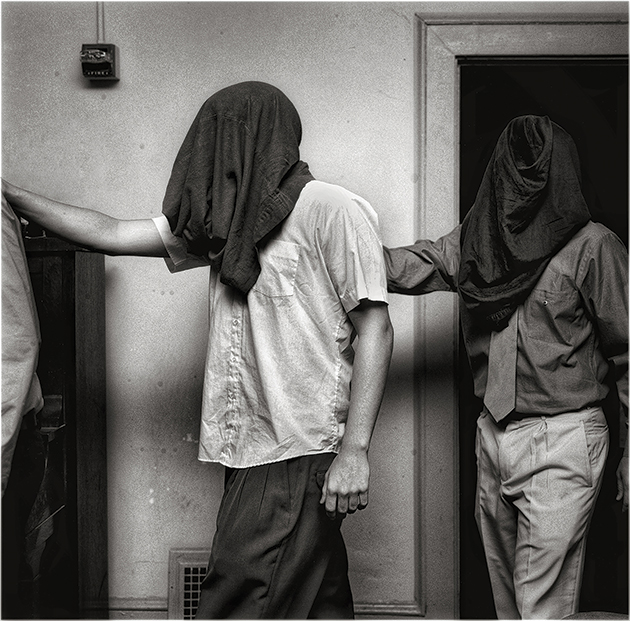

A membership ritual at an unnamed Cal fraternity, from Andrew Moisey’s The American Fraternity

On a Wednesday in mid-October, the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity near the University of California’s Berkeley campus looks all but deserted. The heavy wooden doors are shut and there’s not a “Fiji” in sight. This house was bustling, though, on the previous Saturday. Cal’s football team was playing UCLA, and the front lawn and wide concrete staircases were crowded with students, parents, and alumni drinking and socializing. On the sidewalk out front stood a small group of protesters bearing signs, such as “Boycott Frats” and “Frat Brothers Are 300% More Likely To Commit Sexual Assault.”

Predictably, the Fijis gave the protesters some shit—several bros posed mockingly around the sign-bearers for a photo that eventually found its way to Walker Spence, a senior who had abandoned his fraternity because he was tired of making “excuses for my own complicity.” Spence posted the photo on Facebook. “Men in our society have, especially recently, shown that they couldn’t give a shit about victims of sexual assault,” he wrote. “The privilege and sociopathic lack of empathy displayed in this image is profoundly upsetting.”

Soon the editorial board of the Daily Cal was weighing in: “Greek life is insular, archaic and toxic,” the student paper opined. “Fraternities are held to such a low level of accountability that misogyny grows and spreads, seemingly unfettered.”

This all came amid the furor over Justice Brett Kavanaugh, whose history of alleged sexual assault, heavy drinking, and membership in Yale’s notorious Delta Kappa Epsilon—which in 2010 led its pledges to the campus Women’s Center, where they chanted, “No means yes; yes means anal!”—has fueled ongoing vitriol against Cal’s “Dekes” and its Greek system in general.

I was part of that system. As a Cal student in the mid-1980s, I pledged the Beta Xi chapter of Kappa Sigma. Now, like Spence, I have my misgivings. “Fraternities are the worst,” Vanessa Grigoriadis, the author of Blurred Lines, a book about sex, power, and consent on campus, told me. “There’s absolutely no reason why there should be fraternities, other than the financial incentive on the part of the universities.”

She’s referring to the fact that fraternities and sororities enable colleges to outsource a good portion of housing and social activities, and that Greeks, who tend to come from better-off families than the GDIs (“God-Damned Independents”), are more apt to pay full tuition, donate to their alma maters, and hold positions of power—all potential obstacles for administrators who aspire to abolish fraternities or rein them in.

To its members, the Greek system offers a surrogate family and a lifelong support network. Fraternal organizations like to boast that a who’s who of business and political leaders—including more than a dozen US presidents—were fraternity members. I was well aware that the Kappa Sigma roster included names like Jimmy Buffett, Bob Dole, Edwin Hubble, Robert Redford, Ted Turner, and Edward R. Murrow.

And yet “fraternity has become a bad word,” one brother told journalist Alexandra Robbins, who spent a year documenting Greek life for her excellent new book, Fraternity, out February 6. “I’m very hesitant to say I was in a fraternity because, to certain people, that will mean I was in a culture that promoted sexual assault, I partied my whole way through college, I had no responsibility, and I’m a privileged Caucasian kid who had everything handed to me. That stigma is incredibly incorrect.”

But is it? Robbins, who was a member of a secret society at Yale, recalls contemporary incidents that are appalling even by 1980s standards. In 2010, Kappa Sigs at the University of Southern California circulated an email seeking the lowdown on sorority girls (“who fucks and who doesn’t”) for a “gullet report” the email’s author—who USC’s interfraternity council says was not a student—claimed he was compiling: “The gullet report will strengthen the brotherhood and help pin-point sorostitutes more inclined to put out.” In 2015, at the University of Central Florida, a Sigma Nu was allegedly caught on video yelling, “Let’s rape some bitches” and “rape some sluts,” and chanting “rape” over and over—especially troubling given that months earlier a woman had told police she’d blacked out after drinking at the Sigma Nu house and woken up the next morning, naked and in pain, with a condom wrapper nearby. (No charges were filed.)

That same year, brothers from an Oklahoma chapter of Sigma Alpha Epsilon, a fraternity with deep Confederate roots, were captured on video singing (to the tune of “If You’re Happy and You Know It”) that “there will never be a nigger SAE.” Last April, white members of Lambda Chi Alpha dressed as gangstas for a party—another donned blackface—during California Polytechnic State University’s annual “PolyCultural Weekend.” (The parent fraternity put the chapter on probation.)

Robbins and her researcher created a database of incidents involving America’s roughly 5,600 historically white social fraternity chapters and found, from January 2010 through June 2018, more than 2,100 cases of abusive drinking, hazing, sexual assault, racism, violence, vandalism, and fatalities—and those were just reported incidents they could find online. (In the latest high-profile case, a former fraternity president at Baylor University who was indicted on four counts of sexual assault—the victim said she was drugged and repeatedly raped at a party—walked away with a no-prison plea deal this past December.) From 2005 to 2017, Robbins writes, at least 72 young men died in fraternity-related incidents.

Despite increasing awareness of such events, fraternities have grown more popular, not less. They hit a nadir during the early 1970s, according to Robbins, but were revived by, of all things, Animal House. Now interest is at its highest in decades. The North American Interfraternity Conference (NIC), which oversees 66 fraternities, reported a 50 percent increase in membership from 2005 to 2015.

“College students arrive on campus at the height of a developmental stage where they yearn to belong,” Robbins writes, and half of college men in a large 2017 survey reported feelings of loneliness. “Kids want to be part of things when they’re being told not to be, so there’s that aspect,” Grigoriadis adds, and the social network is a powerful draw. “The idea that there’s a built-in party and you don’t need to go look for it, and the sorority girls will just come to your house and party with you, is incredibly exciting and validating and easy.”

Which raises another concern. The National Panhellenic Conference, which oversees 26 sororities, forbids them from serving alcohol, thereby ensuring that most of the parties happen on male turf, with the bros setting the agenda, buying the booze, and establishing the dress code—often themes like “Little Mermaid” or “toga party,” Grigoriadis says, that encourage women to show up scantily clad.

Panhellenic organizations, Robbins told me, also encourage sororities to party as a way to “keep up relations” with the Greek community. “We believe that regardless of where a party takes place, the efforts needed to create safe campuses and battle sexual assault are universal—requiring a culture shift, not a venue shift,” Dani Weatherford, the NPC’s executive director, said in a statement.

This past September, the NIC and the NPC launched a joint effort to get tougher on hazing. The NIC also took the notable step of banning hard alcohol at fraternity houses and their events effective September 2019, except when it is served by a licensed third-party vendor. “Over the last year, we have been in a period of deep reflection,” a spokeswoman explains. High-proof liquor was “a common denominator” in nearly all hazing and overconsumption deaths over the past two years, and “the conference felt it was critically important to act.”

But it’s not as though this wasn’t a problem a century ago. “The evils of indiscriminate drinking were early recognized and it was lucky that the charter members were of the type to recognize this,” reads a 1911 history of my fraternity chapter, Beta Xi. “They were more thoughtful than the average college student and so the stand that they took against drinking was one to be expected. Scholarship was a thing that they desired among the members and they were successful in no small degree.”

The temperance didn’t last. Booze was plentiful enough at our house during the 1980s, and the hazing was intense. In late 2009, “alcohol and behavior” problems prompted the parent fraternity to revoke Beta Xi’s charter for two years, and a comeback attempt was derailed in 2014 by hazing and further alcohol violations. My old fraternity house, a stone’s throw from the Fiji house, is now rental housing.

My father was taken aback when I told him I’d pledged. As a university professor and administrator, he was familiar enough with the system’s dark side. “The abuses, the things they made people go through with the application process—it brought out stupidity and drunkenness,” he told me. “They were not, for the most part, positive places.”

And that’s probably true, although most of my brothers were upstanding people, and some of them remain my lifelong friends. We studied hard and partied hard. I never heard about any sexual assaults taking place at our house, thank God, but the standard debauchery applied: fights, base sexual language, problematic humor. Spiked punch flowed freely at our annual Hawaiian-themed bash, Kamanawanalei’u. (Get it?) There was also a pimps-and-prostitutes theme party—fun then, but not too cool in hindsight. “We were teenagers doing stupid stuff, like fraternity members in most schools,” one Kappa Sig recalls. But sexual assaults “were not tolerated.”

Maybe, but what did “sexual assault” mean in the 1980s, when moviegoers flocked to rapey comedies like Sixteen Candles? Hell, those lines aren’t even clear today. That an inebriated brother might have had sex with a woman too drunk to give her consent—which did happen at the house of someone I know—is not beyond the realm of possibility. A sorority sister who was a regular at our parties told me she doesn’t recall a predatory vibe. “I don’t know whether to chalk that up to being around the right guys,” she says. “Was I just lucky?” She adds that the women in her sorority were “pretty open,” and “I never heard anybody say, ‘Oh my god, he went too far,’ or ‘I said no and he wouldn’t stop.’”

How might my fraternity brothers have responded to such a complaint? It’s hard to say. I look back at one troubling incident in which a woman accused an older member of pushing her down some stairs. The details were disputed and a few of the younger guys, myself included, accompanied the brother to a Greek disciplinary hearing on campus. I didn’t know whose account was correct, but my presence signaled an allegiance: bros before hos. Such is the power of the group.

Maybe that’s the aspect that bugs me the most, the whole pack mentality. Robbins’ book digs into some psychological aspects of the Greek experience: conformity, groupthink, and group polarization—the tendency of a group to behave more extremely than its individual members would, something we see in politics left and right.

The conformity research is nuts. In the 1950s, Yale psychologist Solomon Asch would bring a student volunteer into a room with seven other subjects who were secretly part of the experiment. The group was shown one card with a line printed on it and a second card containing three numbered lines. The participants were then asked which of the three numbered lines came closest in length to the line on the first card. When the phony participants, by design, converged on an obviously wrong answer, the student volunteer would more often than not choose the wrong one as well. Asch was stunned by this unexpected result, Robbins writes.

She also quotes Yale psychologist Irving Janis, who coined the term “groupthink” and who wrote that its “victims” tend to “keep silent about their misgivings and even minimize to themselves the importance of their doubts.” Which might help explain why Sen. Susan Collins of Maine not only voted for Kavanaugh but also parroted the offensive suggestion that Christine Blasey Ford had been sexually assaulted by someone she mistook for him.

It might also explain why I worried that writing this piece would be a betrayal. I admitted as much to Robbins. “Fraternities are this enormous storied institution of power and prestige that dominates the social culture in higher education,” she said. “And yet men like you are not only hesitant to mention your membership in it because of the connotations, but even now the power of the group affects you, decades later. I mean, that’s kind of fascinating. In college, there’s such a sense of pride for the guys when they belong to fraternities. Some just don’t like to tell people about it after graduation.”

Robbins makes the case that fraternities are not monolithic and that, done right, they can be healthy spaces. Spence, the Cal student who left his house, is not convinced. His chapter was considered “woke,” he says, largely thanks to a member who established a sexual-assault-prevention position and organized consent talks for party guests—but a woman was assaulted nonetheless. (The house expelled the brother.) “As much as I would like to believe that these frats are trying their hardest,” he adds, “it seems as though they’re trying to put in the least effort and get the best optics.”

One of my old brothers indicated he has few regrets and let on that he sometimes shares wild stories of his Kappa Sigma days with acquaintances. But he also told me he would counsel his sons to avoid fraternities. “I just think there was far too much freedom given to 18-year-old boys to figure out right from wrong. I suppose there still is,” he says. “The male brain is not even fully developed for another 10 years. You mix that level of immaturity with unlimited access to alcohol, and you’re going to have potential for serious problems.”