It took 40 years for Michael Jang’s photography career to take off, and to tell you the truth, he’s thrilled.

“This delayed gratification thing? It couldn’t be any better,” Jang says in the kitchen of his house, which is filled with framed prints for his first retrospective show. The prints of various sizes are neatly wrapped in brown paper, stacked against each other, waiting to be taken to the McEvoy Foundation for the Arts. “This, coming when I’m almost 70, instead of peaking when at 30? Come on. It’s great.”

Jang’s patience has resulted in his first monograph, Who Is Michael Jang? (Atelier Éditions) and his first retrospective exhibition, “Michael Jang’s California,” curated by Sandra Phillips, curator emerita of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Not bad for a guy whose photography career was essentially dormant for 40 years.

“It was simply made for fun. Now, it’s the viewer who is deciding the importance of it, not me. My work is done. I made the images. The only thing I’m making decisions now on is presentation.”

Golden Gate Bridge 50th anniversary, 1987

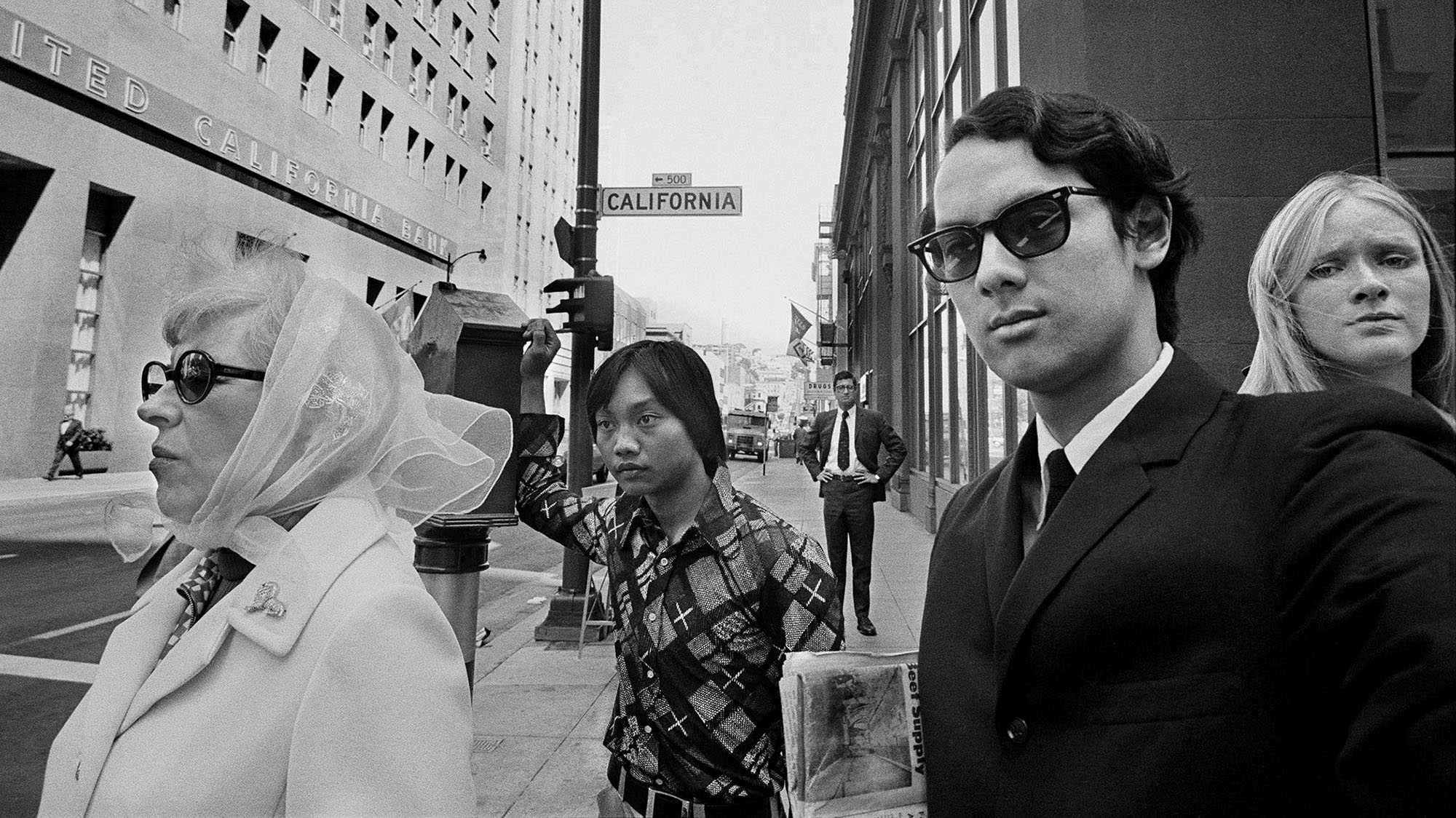

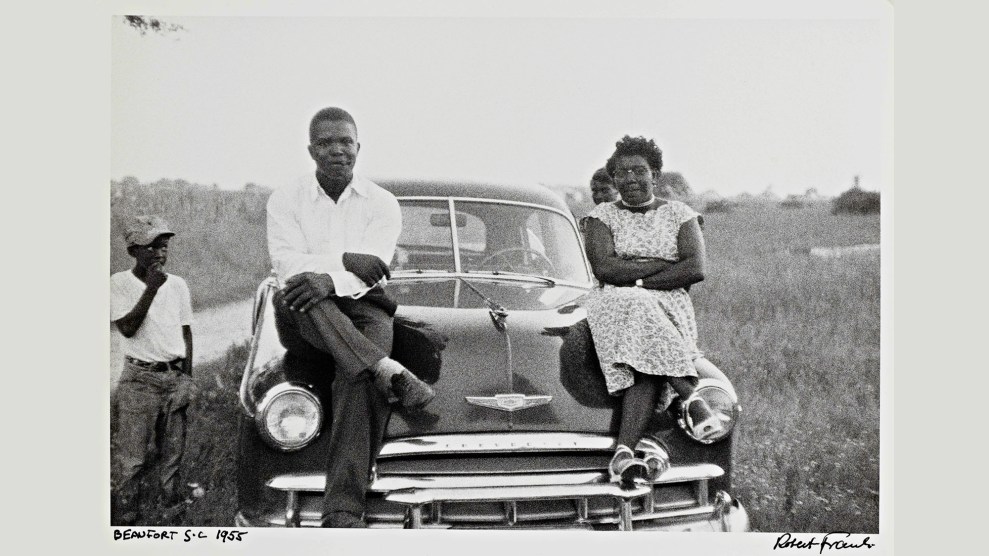

As a young photographer studying at California Institute of the Arts and then the Art Institute in the 1970s, Jang had a transformational experience upon seeing work from the “New Documents” photo exhibition. The show introduced now-legendary New York City street photographers Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand to the art scene and the world at large. Inspired by their work, as well as that of Lisette Model, Jang began to photograph the world around him in a similar style, documenting everyday occurrences in a snapshot aesthetic.

“If there’s anything I took from those guys when they came through Cal Arts or the Art Institute, I learned to just shoot a lot, which isn’t exactly high concept art theory,” he says. “Somehow, intuitively I knew that if I just shot, I would have the goods, because you can’t go back in time.”

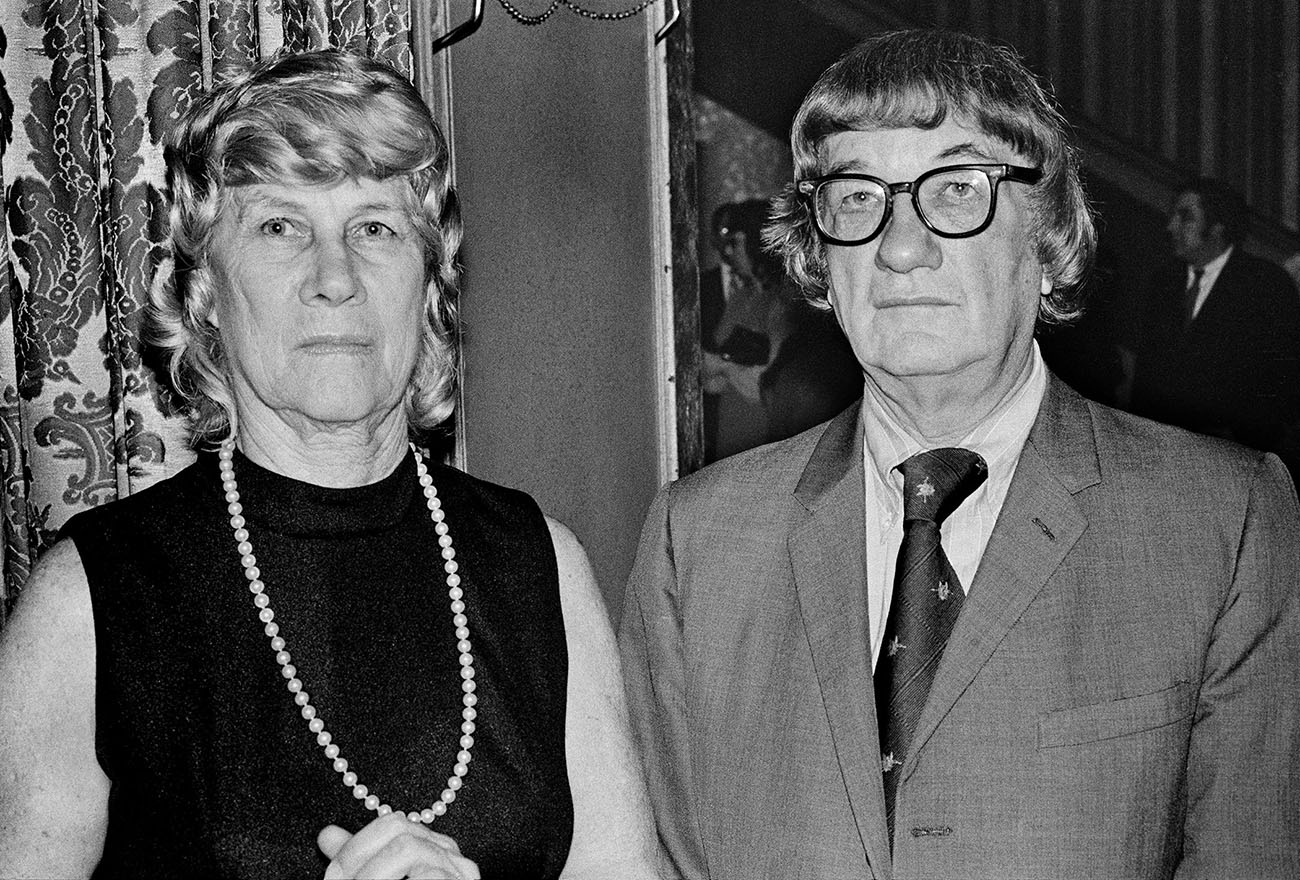

Couple at the Lawrence Welk Dance, 1973

Frank Sinatra, March of Dimes “Man of the Year,” 1973

The resulting photos are loose and wry. Jang’s sharp wit and playfulness bound from his black-and-white images. One body of work, “Beverly Hilton,” came out of his time living in Los Angeles; Jang got a tux and regularly showed up at the Beverly Hilton Hotel like he belonged. He captured the awkwardness of glitzy award dinners in slightly off-kilter photos featuring party-goers and celebrities like Ronald Reagan, Frank Sinatra, and David Bowie, among others.

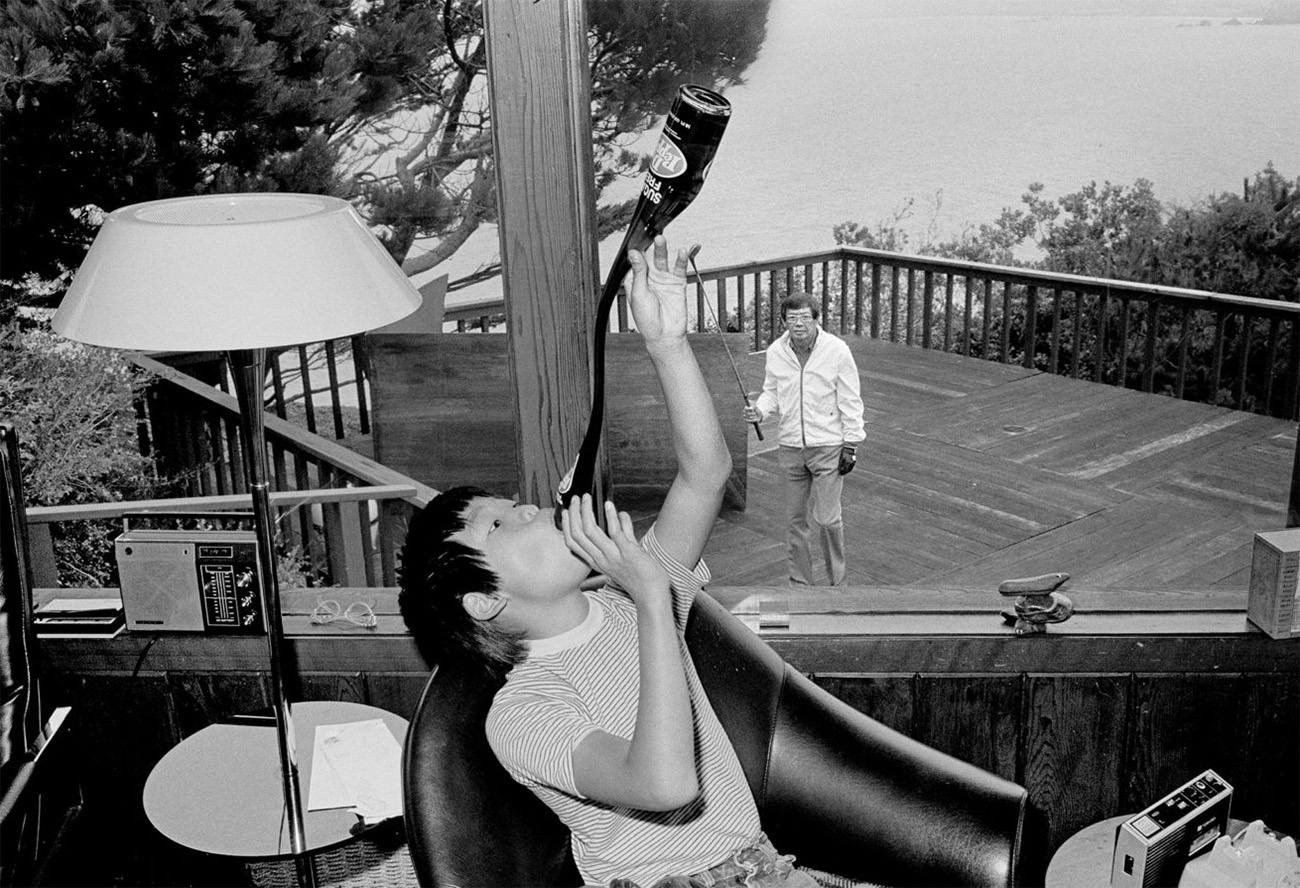

Jang finds particular grist in the ordinary. In 1972 and ‘73, he photographed his classmates for a project simply called “College.” When he spent time visiting his aunt and uncle in 1973, they and his cousins became his subjects. He cast them in silly situations, creating funny juxtapositions in otherwise mundane scenes of daily life; in one, they walk on stilts past a doorway while Jang sits on a chair, seemingly oblivious. If not more interesting, he also caught them living a very all-American suburban existence—devouring Mad Magazine, watching TV, watering the lawn. It’s a fascinating, intimate look at the life in the Bay Area suburbs in the 1970s.

Study Hall, 1973

Chris with elongated Dr. Pepper, 1973

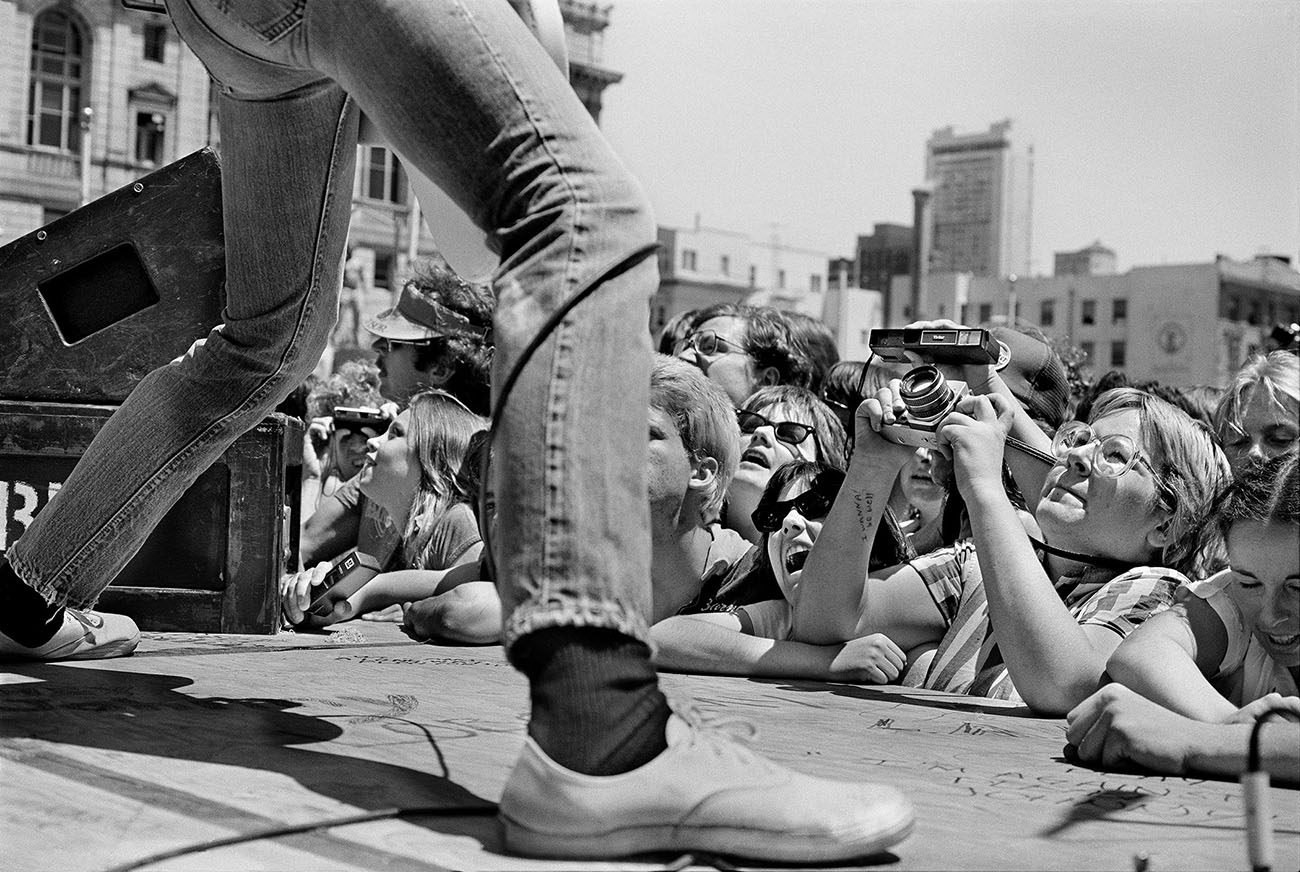

After moving to the Bay Area, Jang photographed punk bands as they toured through town. He shot the Ramones when they played Civic Center, but focused as much on the rapt fans as the band. And while on an otherwise routine corporate headshot assignment at the Miyako Hotel in Japantown, he stumbled across Johnny Rotten from the Sex Pistols the morning after the band infamously imploded during their San Francisco set.

Ramones free concert, Civic Center Plaza, 1979

Like the street photographers who inspired him, Jang also made photos as he wandered around town. His work at news and political events around the city echoes Winogrand’s book “Public Relations,” capturing the media circus around these events, but laced with Jang’s unmistakable eye for irony.

The photos Jang made in the ’70s and ’80s now carry an added value of a vintage patina. The period cars, clothes, and celebrities are all eye-catching, but the work pushes beyond some nostalgia trip. His unmistakable prankster’s sense of humor runs through the work and his photos are fun and quirky without being gimmicky.

One aspect that makes the work hold up, according to Jang, is that “it has a look of not being made for money, or even to design a career; this has the look of just someone just going out and enjoying photography.”

Jang thinks of his craft this way: “There are certain pictures that are classifications, like baby pictures, or sunsets, or maybe even some nudes—they’re immediately likable. But that’s a problem if it’s immediate. I learned that some pictures you have to work on a little bit, you need to come back to. Then I made the connection—that’s like Walker Evans. Do you think he’s going to hit you over the head the first time you see it? No.”

Like Evans’ classic photos, a lot of Jang’s images have a subtle allure that keeps you coming back. Sometimes you see something new, sometimes it’s a matter of trying to unpack what the hell makes you so drawn to the photo.

Lucy watering at night, 1973

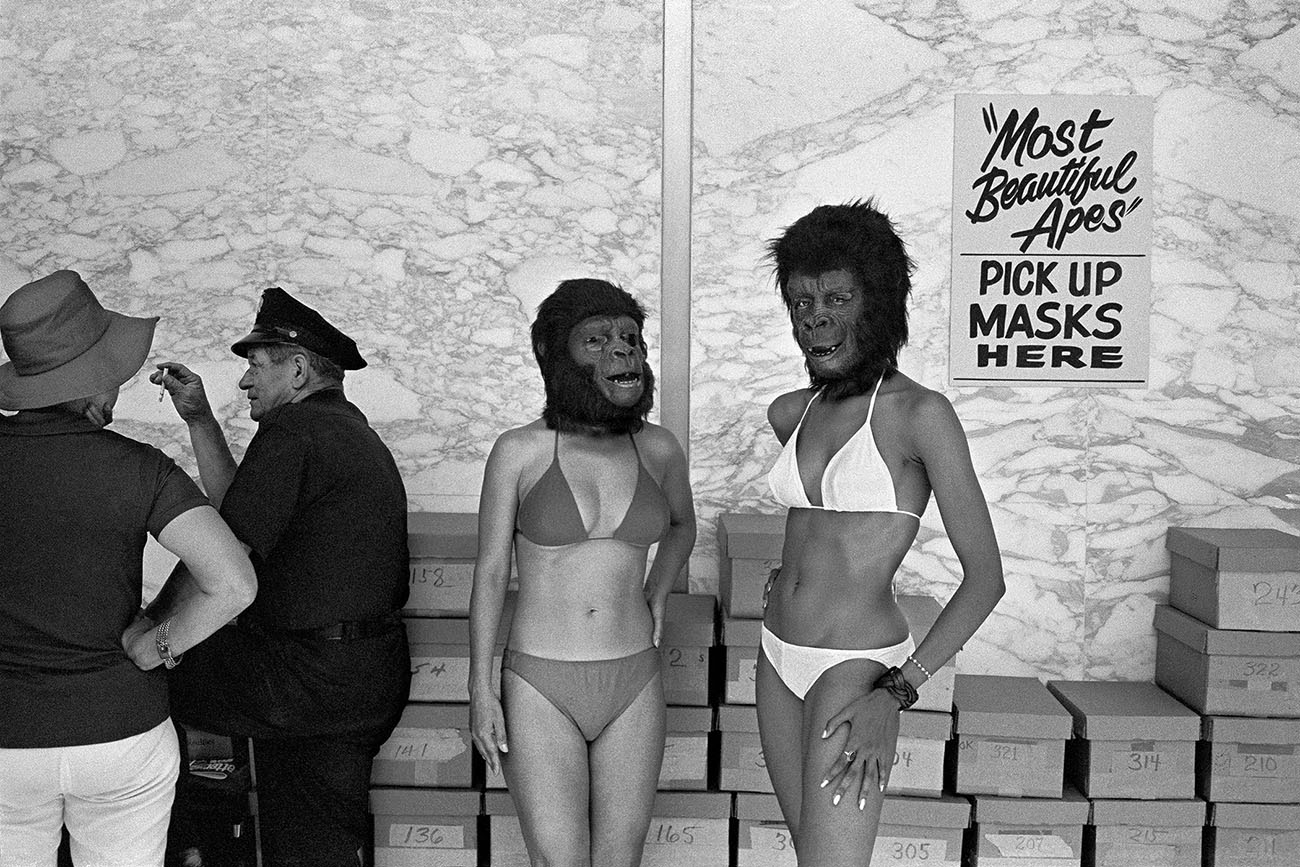

Planet of the Apes beauty contest, Century City, 1973

Jang is not a photographer who overexplains his work—instead, he lets it stand on its own, inviting the viewer to read into it what they want, or just take it as it is.

“One picture getting some notice is the Planet of the Apes beauty pageant,” Jang says, “That’s a bad picture. It’s not quite cropped right. I’ve forgiven myself for that. Enough people like it. It’s been actually attributed to Winogrand online, more than once. So, I thought, ‘Okay, I guess it’s okay.’”

With time and the astute eye of Phillips, Jang has come to really embrace the work he made in the ’70s and ’80s. “Time is forgiving,” Jang says about his early photographs. “Sandy has always found pictures that I never even considered were good. Through her, I learned more about my own work.”

Onlookers at George Moscone funeral, 1978

In 2001, Jang revisited the photos he made in the ’70s and early ’80s. He dropped off a box of prints at the SFMOMA. To his surprise, he got a call a few weeks later—Phillips, then head curator of the photography department, wanted to meet. The photography department rarely called in photographers who took advantage the of the open drop-off policy. It was a critical moment in Jang’s career.

“I know my steps. I’ve traced them back. That drop off at SFMOMA was key.”

It took over 20 years from the point Jang made the work to that game-changing meeting with Phillips. It would be almost another 20 years for that decision to really pay dividends in the form of his retrospective book and exhibition.

The exhibition, curated by Phillips, centers Jang’s work around those early influences: Friedlander, Winogrand, and Arbus. The first of three rooms is the nucleus of the exhibit; it’s focused on their work, with the addition of notes, letters, and self-portraits from early in Jang’s career. The second room includes small, original prints Jang made while in school, showing Jang developing into what he becomes in the third room—a modern, thoughtful photographer. Big prints, up to six feet, and wheat-pasted photos mixed with graffiti break the traditional gallery presentation of photographic work. Jang is having fun the with exhibition, as has always been key to his work.

David Bowie signing autographs, 1973

After letting these images marinate for 40 years, Jang is ready for his moment. He likewise encourages young photographers to be patient.

“It’s just a different mindset today. It’s the same way in seeking fame, like you see in music. You want it now. I wouldn’t suggest anyone wait as long as me–you might die. But somewhere in the middle, you know. Learn some stuff, educate yourself and understand where your work is in relation to everything else that’s been done, and where it might be currently, and in the future. That it’s a good thing to figure out if you can.”

Who Is Michael Jang? is available from Atelier Éditions; Jang’s retrospective Michael Jang’s California will be on display at the McEvoy Foundation for the Arts from September 27, 2019 through January 18, 2020.