The fall of an empire is supposed to be a dramatic thing. It’s right there in the name. “Fall” conjures up images of fluted temple columns toppling to the ground, pulled down by fur-clad barbarians straining to destroy something beautiful. Savage invasions, crushing battlefield defeats, sacked cities, unlucky rulers put to death: These are the kinds of stories that usually come to mind when we think of the end of an empire. They seem appropriate, the climaxes we expect from a narrative of rise, decline, and fall.

We’re all creatures of narrative, whether we think explicitly in those terms or not, and stories are one of the fundamental ways in which we engage with and grasp the meaning of the world. It’s natural that we expect the end of a story—the end of an empire—to have some drama.

The reality is far less exciting. Any political unit sound enough to project its power over a large geographic area for centuries has deep structural roots. Those roots can’t be pulled up in a day or even a year. If an empire seems to topple overnight, it’s certain that the conditions that produced the outcome had been present for a long time—suppurating wounds that finally turned septic enough for the patient to succumb to a sudden trauma.

That’s why the banalities matter. When the real issues come up, healthy states, the ones capable of handling and minimizing everyday dysfunction, have a great deal more capacity to respond than those happily waltzing toward their end. But by the time the obvious, glaring crisis arrives and the true scale of the problem becomes clear, it’s far too late. The disaster—a major crisis of political legitimacy, a pandemic, a climate catastrophe—doesn’t so much break the system as show just how broken the system already was.

Comparisons between the United States and Rome go back to the very beginning. The first volume of Edward Gibbon’s magisterial The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was published in 1776, the year of the Declaration of Independence. The Founding Fathers had a deep appreciation and understanding of classical antiquity, and to some extent, they modeled aspects of their new nation on that understanding of the Roman past. Southern planters retained a distinct fondness for the Roman aristocracy, cultivating a life of high-minded leisure on the backs of chattel slaves.

As at the beginning, so too at the end. If anybody knows anything about Rome, they know that it fell, and they usually have a theory—lead poisoning is a popular one—to explain why. Every scholar working on Roman history has faced the linked questions of whether we’re Rome and where we are in the decline and fall. Those twin queries might come from students, casual acquaintances at a mandatory social function grasping for conversational common ground, some guy at a party ripping massive bong hits to whom you made the mistake of telling your occupation, or, in my case, from podcast listeners and people on Twitter.

I spent the better part of a decade thinking about the end of the Roman Empire in its various manifestations. Academics, being academics, agree on very little about the topic. The idea of “fall” is now passé, for better and for worse; scholars prefer to speak of a “transformation” of the Roman world that took place over centuries, or better still, a long, culturally distinct, and important-in-its-own-right Late Antiquity spanning the Mediterranean world and beyond. If the Roman Empire did ever come to a real end, all agree, it was a slow process lasting many lifetimes—hardly the stuff of dramatic narratives. There are still a few catastrophists out there, but not many.

On one hand, this is all beside the point. While the eastern half of the Roman Empire survived in some form for another thousand years, brought to an end only by the Ottoman sultan Mehmed the Conqueror in 1453, the empire in the west did in fact come to a sharp end. After a certain point, either 476 (Romulus Augustulus) or 480 (Julius Nepos), there was no longer an emperor claiming authority over the vast territory Rome had encompassed, stretching from the sands of the Sahara to the moors of northern Britain. Supply wagons laden with grain and olive oil for Roman garrisons no longer rolled along roads maintained at state expense. The villas everywhere from Provence to Yorkshire in which Roman aristocrats had passed their time, plotting their election to town councils and composing bad poetry, fell into ruin.

Depending on the time, place, and identity of the observer, this process could look and feel much different. Let’s say you were a woman born in a thriving market town in Roman Britain in the year 360. If you survived to age 60, that market town would no longer exist, along with every other urban settlement of any significant size. You lived in a small village now instead of a genuine town. You had grown up using money, but now you bartered—grain for metalwork, beer for pottery, hides for fodder. You no longer saw the once-ubiquitous Roman army or the battalions of officials who administered the Roman state. Increasing numbers of migrants from the North Sea coast of continental Europe—pagans who didn’t speak a word of Latin or the local British language, certainly not wage-earning servants of the Roman state—were already in the process of transforming lowland Britain into England. That 60-year-old woman had been born into a place as fundamentally Roman as anywhere in the empire. She died in a place that was barely recognizable.

Let’s consider an alternative example. Imagine you were lucky enough to have been born the son of an aristocrat in Provence around the year 440. If you survived to the age of 60, your life at the end would not seem drastically different from what it was at the beginning. You paid your taxes, assuming you couldn’t dodge them, to a Burgundian or Visigothic king rather than a Roman emperor. Other than that, your life was pretty much the same. You still had your fancy villa with its bathhouse and library and comfortable furniture. You still wrote letters to your aristocratic friends and relatives in an educated Latin style so tortured that it was more of a status-signaling device than a means of communication. You still played politics in the nearest city, which was mostly as it was at the time of your birth: fewer people maybe, a local bishop with more influence, the buildings a bit more run down, but still recognizable. In your more self-aware moments, perhaps you recognized that the world had changed since your youth, but it wasn’t a huge concern. That aristocrat’s life changed little in material or ideological terms.

Yet even in the most extreme cases of rapid transformation, like Britain, northern Gaul, and the Balkans, the day-to-day experience of living in a falling empire could be surprisingly banal. The tax collectors didn’t show up, which meant lower revenues for the provincial administration. A crumbling bridge and road never got the necessary repairs, so a formerly prosperous town was cut off from the transport network. Without revenues, pay and supplies of grain and wine never arrived for the local soldiers, who decided they would no longer carry out patrols to protect against marauders. That was when the banal might suddenly become much more serious: Without soldiers, a talented barbarian war leader on the other side of the frontier decided to try his hand at raiding formerly protected territory. After some successful pillaging, that barbarian came back the next time with an army.

The fall of an empire—the end of a polity, a socioeconomic order, a dominant culture, or the intertwined whole—looks more like a cascading series of minor, individually unimportant failures than a dramatic ending that appears out of the blue. Supply carts failing to arrive at some nameless fort because of a dysfunctional military bureaucracy; a corrupt official deciding to cook the books and claim taxes were collected when they really weren’t; a greedy aristocrat bribing that official instead of paying his bill, an aqueduct falling to pieces and nobody willing to front the funds to repair it.

Consider the city of Rome, no longer the capital as the empire wound down but still its symbolic heart. It suffered two dramatic sackings in the 5th century, the first at the hands of the Visigoths in 410, the second carried out by the Vandals in 455. But neither of those famous plunderings did the city in. By some estimates, Rome still had at least 100,000 inhabitants well into the barbarian Ostrogoths’ period of rule. What shrank Rome to a few tens of thousands by the middle of the 6th century was the end of the annona, the intricate state-subsidized grain shipments that brought food to the city from North Africa and Sicily. The megacity of Rome was an artificial creation of the Roman state and its Roman-style Ostrogothic successor. Rome faced sieges and a plague outbreak in the 530s and 540s, but Rome had dealt with sieges and plagues before. What it could not survive was the cutting of its grain supply, and the end of the administrative apparatus that ensured its regular delivery.

Those were small things, state-subsidized ships pulling up to docks built at state expense, sacks of grain hauled on squealing carts and distributed to the citizens, but an empire is an agglomeration of small things. One by one, the arrangements and norms that enabled those small things fell away; not all at once, not everywhere, but slowly and inexorably. That’s the reality, far more than a climactic battlefield defeat or a deranged emperor single-handedly ruining a stable structural arrangement.

None of this is to say that there weren’t climactic battlefield defeats and wild disasters as the Roman Empire in the west and the Roman world came apart in slow, tortuous, almost imperceptible fashion. Incompetent rulers and psychopathic powers behind the throne did their part. Plagues appeared out of nowhere, killing millions. The climate slowly worsened, growing less stable and colder, with more frequent droughts and a less dependable growing season for key staple crops. The late Roman Empire faced enormous challenges, both natural and human-made. There’s no doubt of that.

Yet every state and society faces serious challenges. The difference lies in whether the underlying structures are healthy enough to effectively respond to those challenges. Viewed in this light, it’s less the massive earthquake than whether the damaged infrastructure is rebuilt; not the crushing battlefield defeat, but whether competent new recruits and materiel can be found to replace what’s lost; not the feckless, unclothed emperor, but whether the political system can either effectively work around him or remove him from power altogether. Successful states and societies are resilient when faced with serious challenges. Falling empires are not.

Whatever date you pick for the fall of the Roman Empire—perhaps you’re a 476 traditionalist, or maybe you’re like me and you prefer the turbulent wave of downturns in the 530s and 540s—the relevant fact is that the die was cast long before then. The same will eventually be true of the fall of the United States, assuming there’s anybody left in our climatically uncertain future to write that history. All empires think they’re special, but all empires eventually come to an end. The United States won’t be an exception.

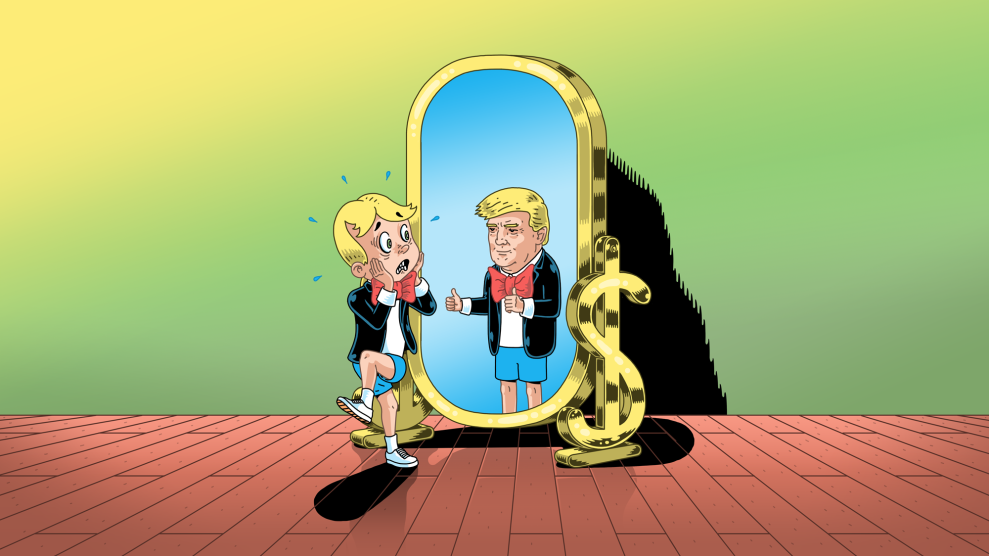

The popular story version of this particular falling empire might focus on a twice-divorced serial philanderer and bullshit artist and make him the villain, rendering his downfall or ultimate triumph the climax of the narrative. But it’s far more likely that the real meat of the issue will be found in a tax code full of sweetheart deals for the ultra-wealthy, the slashed budgets of county public health offices, the lead-contaminated water supplies. And that’s to say nothing of the decades of pointless, self-perpetuating, and almost undiscussed imperial wars that produce no victories but plenty of expenditures in blood and treasure, and a great deal of justified ill will.

Historians will look back at some enormous disaster, either ongoing now or in the decades or centuries to come, and say it was just icing on the cake. The foundation had already been laid long before, in the text of legislation nobody bothered reading, in local elections nobody was following, in speeches nobody thought were important enough to comment on, in a thousand tiny disasters that amounted to a thousand little cuts on the body politic.

It took a long time, decades, for the true reality of the change to hit the Romans whose writings have survived. Aristocratic Roman officials in Italy maintained the same kind of bureaucratic structure their fathers and grandfathers had, writing the same kinds of administrative letters for Ostrogothic kings of Italy that they had for emperors beforehand. The pull of the past is strong. The mental frameworks through which we understand the world are durable, far more than its actual fabric. The new falls into the old, square pegs into round holes no matter how poor the fit, simply because the round holes are what we have available.

We don’t have to wait decades for all this to sink in. The nature of the problem and its scale are clear now, right now, on the cusp of the disaster. Maybe those future historians will look back at this as a crisis weathered, an opportunity to fix what ails us before the tipping point has truly been reached. We can see those thousand cuts now, in all their varied depth and location. Perhaps it’s not yet too late to stanch the bleeding.

Patrick Wyman is the host of the Tides of History podcast and the former host of The Fall of Rome Podcast. He has a PhD in history.