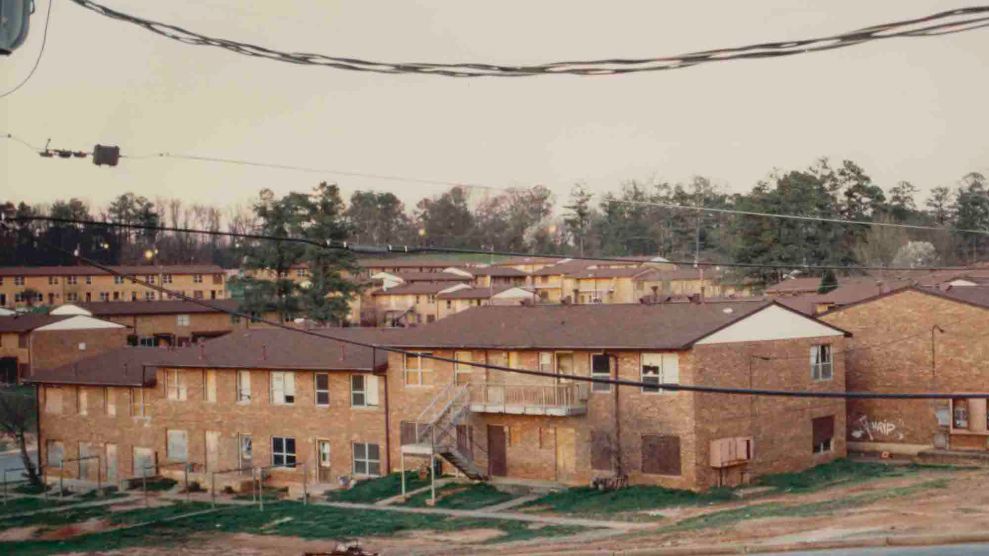

An aerial view of East Lake Meadows circa 1996.Tim Huber/courtesy of PBS

Aseelah Muhammad’s new life at East Lake Meadows got off to a good start. It was the mid-1990s, she was 19, and the Atlanta public housing complex was her only real option for a place to live with her husband and three daughters. She knew East Lake’s reputation—people called it “Little Vietnam,” for the violence that had consumed the complex in the depths of the crack epidemic—but she was happy to be moving in, the kids were happy, and the weather was nice on move-in day.

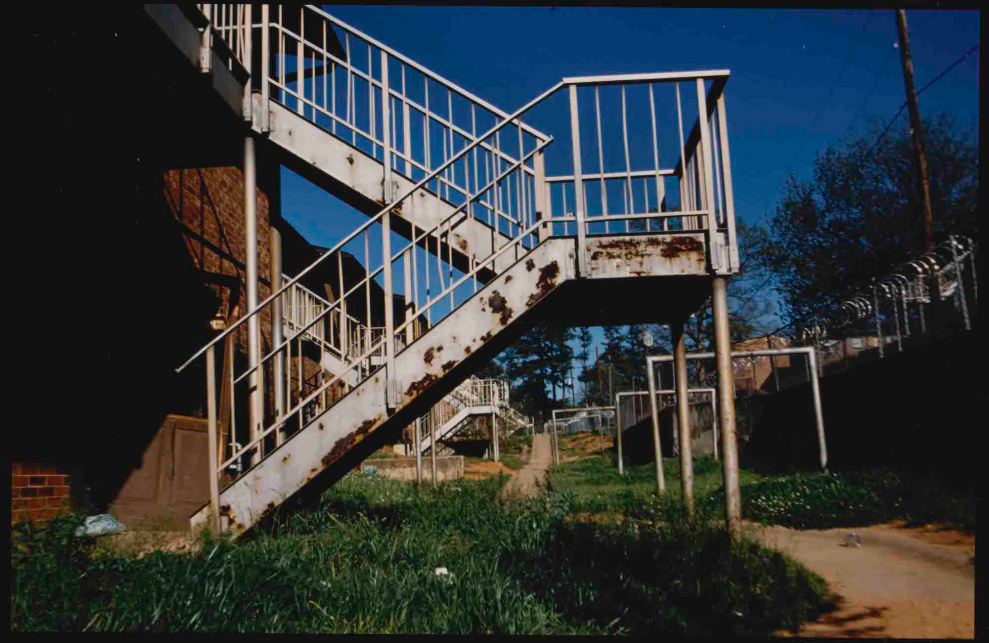

Then she heard gunshots. She soon learned that someone had been killed right under the stairs that led to her new home.

The good times had lasted maybe two hours.

And so, not long after, when the city’s housing authority presented a plan to tear down East Lake Meadows and rebuild it as a mixed-income community, Muhammad joined three-quarters of her neighbors in voting to support the proposal.

Similar stories were playing out across the country. New Deal–era programs had created public housing as a way to house the (largely white) working class. But as federal assistance provided a path for white families into the middle class and the booming suburbs, public housing complexes became segregated enclaves for Black Americans without access to that assistance, and buildings fell into neglect and disrepair. Drug dealing and violence preyed on these communities of concentrated poverty, earning them a national reputation as epicenters of urban decay.

A rusted stairwell at East Lake Meadows

Tim Huber / courtesy of PBS

But in contrast to the urban renewal that had bulldozed Black neighborhoods a few decades earlier to make way for freeways and sterile architecture, the demolition of public housing wasn’t simply a form of displacement being imposed on communities of color. In some cases, those communities themselves were demanding it.

That complexity is captured in East Lake Meadows: A Public Housing Story, a PBS documentary premiering today, directed by the wife-and-husband team Sarah Burns and David McMahon and executive produced by Burns’ father, Ken Burns. As cities around the country continue to contemplate what to do with their crumbling public housing, the film offers a glimpse into the demand by public housing occupants for something better.

The trouble is that often, something better doesn’t come. At least not for them.

“Our record, nationally, of getting the original families back on site is ridiculously bad,” Edward Goetz, an urban planning professor at the University of Minnesota, says in the film. “We made better places, but we by and large didn’t make better places for the people who originally lived there.”

East Lake Meadows is now a gated community called the Villages of East Lake. The old neighborhood lacked a supermarket or bank; the new one has a Publix and a Wells Fargo, not to mention a YMCA, a daycare, and a charter school. The distressed low-rises have given way to McMansion-esque buildings and townhouses. Half of the new housing units are reserved for low-income residents. But despite the city’s promise that all East Lake Meadows residents would be entitled to return, only 15 percent have.

Aseelah Muhammad

Courtesy of PBS

Some of the others were kept out by strict criteria that excluded residents with criminal records—barring entire multigenerational families if one teenage member had gotten into trouble. Many, including Muhammad, opted to take Section 8 vouchers and look for housing on the private market. “It was a hard struggle finding someone who would accept a voucher,” she tells Mother Jones. “But we knew we didn’t want to live in any low-income areas.” She eventually found a three-bedroom split-level house in Grayson, 30 miles from downtown Atlanta. She credits the move away from public housing with helping her land a job with Kaiser Permanente and gain financial independence.

“It changed my life,” she says. “It changed my way of thinking, my lifestyle, where I didn’t have to depend on the government for everything.”

But it’s hard to take seriously the promises of cities to keep their public housing communities intact when only a small share of residents end up returning. Sometimes, these conversions take decades to complete, so even when residents are technically guaranteed a spot in the new development, they may have long since moved away, settled into other neighborhoods, or died.

Since the early 1990s, one quarter of the country’s public housing has been eliminated, and Atlanta has demolished all of its family public housing. Earlier in the primary season, some of the Democratic candidates for president, particularly Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, called for a substantial funding boost for subsidized housing, including public housing. Warren has also led the way in trying to clear barriers to the production of more private housing so that supply can begin to catch up with demand and slow the rise of housing costs.

“We need more housing in this country, full stop,” Sarah Burns says. “Not just public housing. Perhaps we should be thinking about building on a much larger scale. So instead of replacing them with fewer units of public housing, we should be replacing them with more.”

In the absence of a massive injection of funds—a political longshot, given the still-troubled national reputation of the “projects”—cities will continue to face the conundrum of what to do with their seriously distressed public housing stock. The documentary calls itself a public housing story, but it uses the example of East Lake Meadows to argue that, often, the only path out of a deteriorating status quo is through the market, even if it means displacing people.

“It’s not black and white,” says Sarah Burns of the East Lake Meadows transformation. “There are things that are really positive about the new community. For people who live there, it is in many ways a safer, healthier, more successful place to live.” She adds, “The biggest question is: Are we serving well the people who need our help the most?”

A woman sweeps outside her East Lake Meadows apartment in the early 1980s.

Rosetta Heath / courtesy of PBS