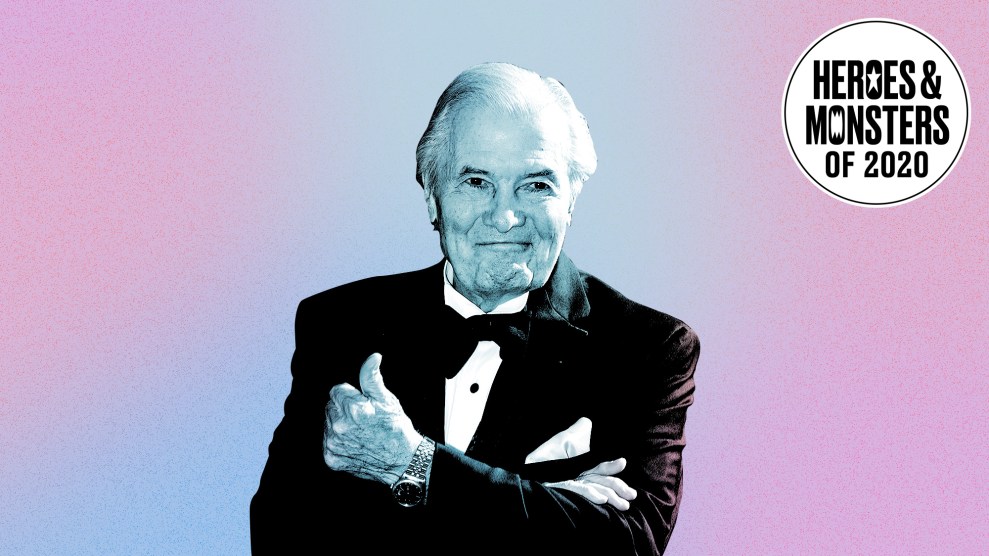

Christian Cooper; Mother Jones Illustration

When I first read about Christian Cooper, the Black birder whose encounter this summer with a white woman in Central Park sparked a national reckoning around racism and policing, I couldn’t help but be drawn to a little-known part of his backstory. In addition to being one of New York’s best-known birding enthusiasts, Cooper was, I learned, a pioneering comics editor. He created the first queer characters in the Star Trek and Marvel fictional universes. Two decades before he was falsely accused of threatening a woman in Central Park (and then refused to aid police), Cooper became one of the first openly-gay editors at Marvel. He was one of the company’s few Black creators, too.

I don’t know much about birds, but superhero comics have been a major part of my life since I first stumbled upon a black-and-white collection of Fantastic Four in sixth grade. I took to Marvel and quickly memorized the names of the creators responsible for my favorite characters.

The popular history of the comics industry has never been a perfect reflection of its actual history—that’s why you’ve seen dozens of Stan Lee movie cameos, and probably haven’t heard the name “Jack Kirby.” But, still, I was surprised that it took some comics bloggers pointing it out for me to learn about Cooper’s work at Marvel and his trailblazing contributions to queer representation in comics.

As a writer on Star Trek: Starfleet Academy, which was published by Marvel in the mid-1990s, Cooper created Yoshi Mishima, the long-running franchise’s first gay character. He also introduced Victoria Montesi, the first openly lesbian character in the Marvel universe and one of the first queer characters to headline a Marvel or DC book. The daughter of a mystical, primordial deity, she searches the globe as a kind of occult investigator.

“I wasn’t trying to hide the relationship with her lover, Natasha, but it was mostly off-screen,” Cooper told Yahoo earlier this year. “There was no negotiation needed on that with Marvel, maybe because it was two women. There’s this weird double-standard about two women together not being nearly as threatening as two guys together.”

Cooper had long connected comics with the gay experience. Like many queer comics fans, he gravitated to the X-Men—heroes who were a “perfect parable for the gay experience,” he told Wired. “The X-Men looked like everyone else, but they learned a deep secret in adolescence that made them different. They were feared and hunted by society, but they just wanted to make the world better.”

Still, others viewed the comics differently. Cooper had difficulty when a book he was editing, Alpha Flight, about a Canadian super-team, revealed that one of its members, Northstar, was gay. “The higher-ups tried to pull the issue from the printer before it was printed, but they were too late, thank god,” he recalled. Northstar, who eventually took up a recurring role in the X-Men books, got married on panel in 2012, twenty years after Cooper first helped him out of the closet.

After leaving Marvel in 1996, Cooper started publishing a webcomic, Queer Nation, at the dawn of the the online comics boom. With comic book stores still generally seen as a hangout for white straight guys, webcomics were a way to reach new readers. No longer bound by the prudish rules of mainstream comics, Cooper wasn’t afraid to get experimental—or graphic. “Foul language, ridiculous situations, intense political commentary…we did it all,” he told Yahoo. “People would react pretty much instantaneously.”

Eventually, Cooper left the comics business and Queer Nation folded up shop with him. Over the summer, as Cooper has done interviews about the Central Park incident, he’s expressed a desire “to take Queer Nation out of mothballs.”

“It has a certain urgency right now that maybe it didn’t have back then,” he said, “because one of the core plot points is that a crazy right-wing fascist has been elected president and is pandering to the religious right. Oh wait, that couldn’t happen in real life!”

That dream edged closer to reality in September, when DC published his original comic, “It’s a Bird.” The story, a loose retelling of his encounter with Amy Cooper, draws a visual link between his experience and the death of George Floyd, which happened on the same day. “I think that is the beauty of comics, it lets you reach that place visually and viscerally,” he told the New York Times. “And that’s what this comic is meant to do: Take all these real things that are out there and, by treating them in a magical realist way, get to the heart of the matter.”

If there’s any good that came from that awful incident, it’s that Christian Cooper is making comics again.