With Donald Trump grabbing the public gaze one last time via the valedictory assault on the Capitol that he inspired, the media had scarce bandwidth to debate damning disclosures that came the next day about the ethics of one of the most consequential journalism coups of the past half-century: the 1971 publication of the Pentagon Papers, the top-secret government history of the United States’ war in Vietnam.

The new disclosures were contained in a riveting account in the New York Times, which has long had an honored place in journalism’s hall of heroes for publishing the Papers. Deservedly so: The Times defied fierce government pressure and won a landmark US Supreme Court ruling allowing it to make the Papers public and expose, in irrefutable detail, decades of official ineptitude and deceit in a war that killed more than 58,000 Americans and as many as 3 million Vietnamese. The Pentagon Papers didn’t end the war, which went on for nearly four more years, but the leak did prompt the Nixon administration to create an illegal special ops unit that bungled the Watergate break-in and cost Richard Nixon his presidency. In a profound way, the Papers taught a generation that the government’s fundamental claims about war and peace could not be believed, nor its intentions trusted.

The Pentagon Papers cemented that fact. But the new Times account describes a dark underside to that journalistic triumph. It is based on a lengthy 2015 interview given by the Times’ lead reporter on the case, Neil Sheehan. For reasons that go pointedly unexplained in the new reporting, Sheehan had agreed to discuss his role in the affair only on condition that the interview not be published during his lifetime. He died January 7, and an account of that interview, by Times veteran Janny Scott, ran later that day.

At the ethical core of Sheehan’s interview are his dealings with his principal source, defense analyst Daniel Ellsberg, a co-author of the Papers and the person who leaked them to Sheehan. Their relationship has been described before, notably by Ellsberg in his gripping 2002 memoir, Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers. But because this new Times account is based on an interview with the previously reticent Sheehan—a towering figure whose book on the war, A Bright Shining Lie, is rightly regarded as a classic—those of us who closely follow the media approached it with special anticipation in the hope that it would deepen our understanding of a resonant moment in press history.

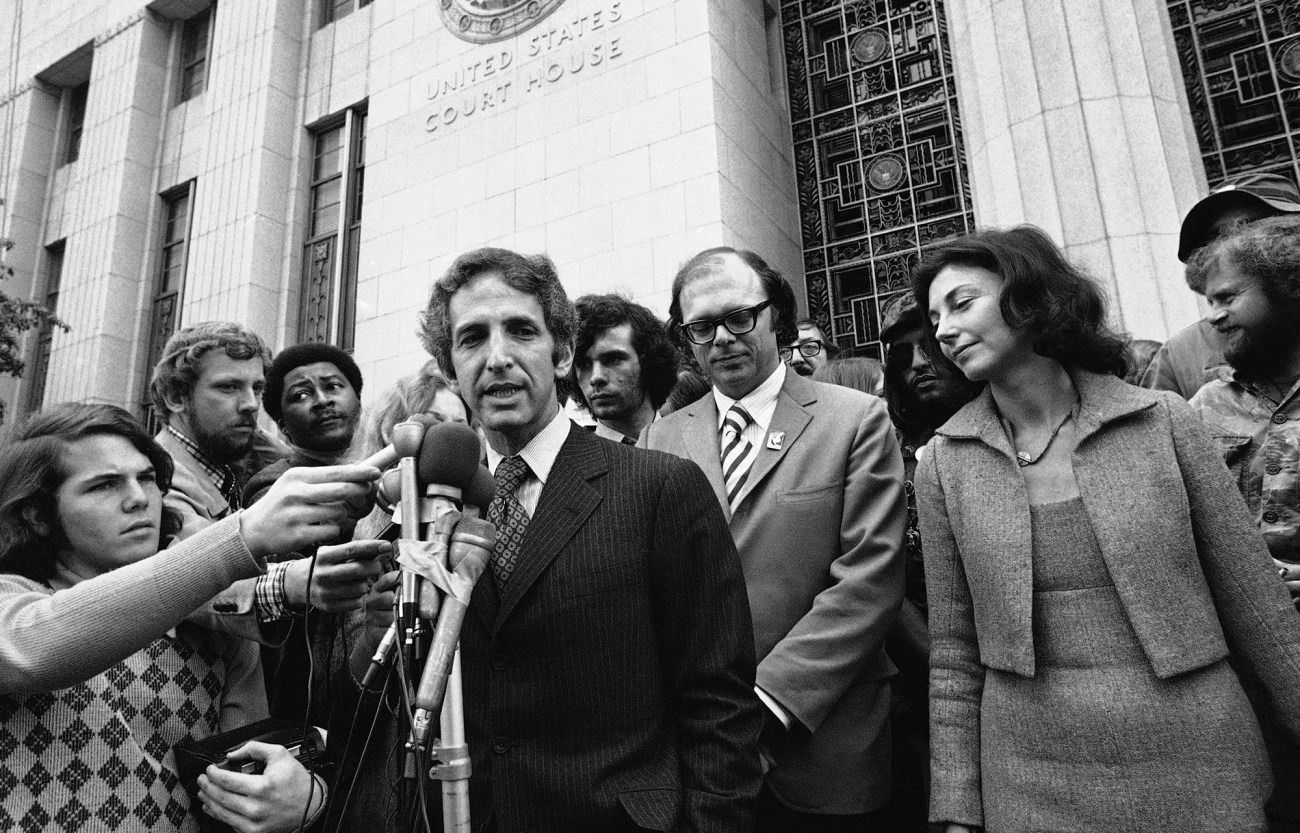

Daniel Ellsberg talks to the press outside the federal courthouse in Los Angeles on January 17, 1973, during the Pentagon Papers trial.

Wally Fong/AP

It does that, but in unexpected and unwelcome ways. That’s because there’s another dimension to the story, one that is deeply disturbing at a time when today’s whistleblowers are mishandled harshly and punitively by federal law enforcement and the courts. And whistleblowers are squeezed from both sides, treated with a lack of regard bordering on arrogance by many in the media whom whistleblowers often risk their jobs and their freedom to partner with.

Because the Times, for all its flaws, has such outsize influence on journalists as a model of reporting standards and practices, the implications of how Sheehan says he treated Ellsberg in that watershed moment—compounded by the Times’ own framing of Sheehan’s recollections—deserve careful scrutiny.

For starters, it’s hard to ignore the way the posthumous interview was couched, from the headline—“How Neil Sheehan Got the Pentagon Papers”—to the framing of a “blockbuster scoop,” “arguably the greatest journalistic catch of a generation,” and the assertion that, while living, Sheehan had declined to explain “how he had pulled it off.”

Here let me say, in the interest of full disclosure, that I have a cordial professional relationship with Ellsberg, a member of the advisory board of the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, which I’m proud to have led. On numerous occasions he has been invited to tell students about the Pentagon Papers, always an immensely inspiring session.

But as his memoir makes clear, for two years before the Times’ 1971 stories ran, Ellsberg had been trying to get the Papers, which he laboriously and illegally photocopied, published. Ellsberg also attempted to get anti-war senators to insert the entire top-secret 7,000-word text in the Congressional Record.

Two of those senators suggested he try the Times instead, so Ellsberg called Sheehan. They had known each other in Vietnam, and Ellsberg says he had leaked to him several stories back in March 1968. Now, three years later, during a nightlong conversation, he told Sheehan about the Pentagon Papers, and Sheehan was interested.

So when Ellsberg knocked, the Times, to its credit, opened the door. But the notion that the Papers constituted a “journalistic catch” that an admittedly great reporter “pulled off” is an unfortunately familiar denial of agency to a highly principled news source, one who courts legal and professional disaster by bringing critically important realities to light. If anyone pulled the story off, it was Ellsberg, not the Times. Indeed, for two years after the Times got its Pulitzer for the coverage that he made possible, Ellsberg and his co-defendant continued to face trial for Espionage Act violations, for which Ellsberg faced a potential sentence of 115 years, without legal or material support of any kind from the media to whom he furnished a prize-winning trove of historic importance. The Times’ Supreme Court victory—while setting a crucial First Amendment precedent—did nothing to keep him from serious criminal prosecution, which fell apart only after Nixon’s vicious efforts to discredit him were exposed.

But the most startling admission in Sheehan’s interview is that he deliberately and repeatedly deceived his source. Ellsberg was reluctant to give Sheehan copies of the Papers. Instead, he let Sheehan review the material and take copious notes, but wouldn’t let him photocopy the documents until he was satisfied the Times was going to do something with them.

Sheehan says he agreed to those conditions, but it’s not clear he ever intended to uphold them. In the 2015 interview, he said, “I’d known Ellsberg for a long time, and he thought I was operating under the same rules that one normally used: Source controls the material. He didn’t realize that I had decided: ‘This guy is just impossible. You can’t leave it in his hands. It’s too important and it’s too dangerous.’”

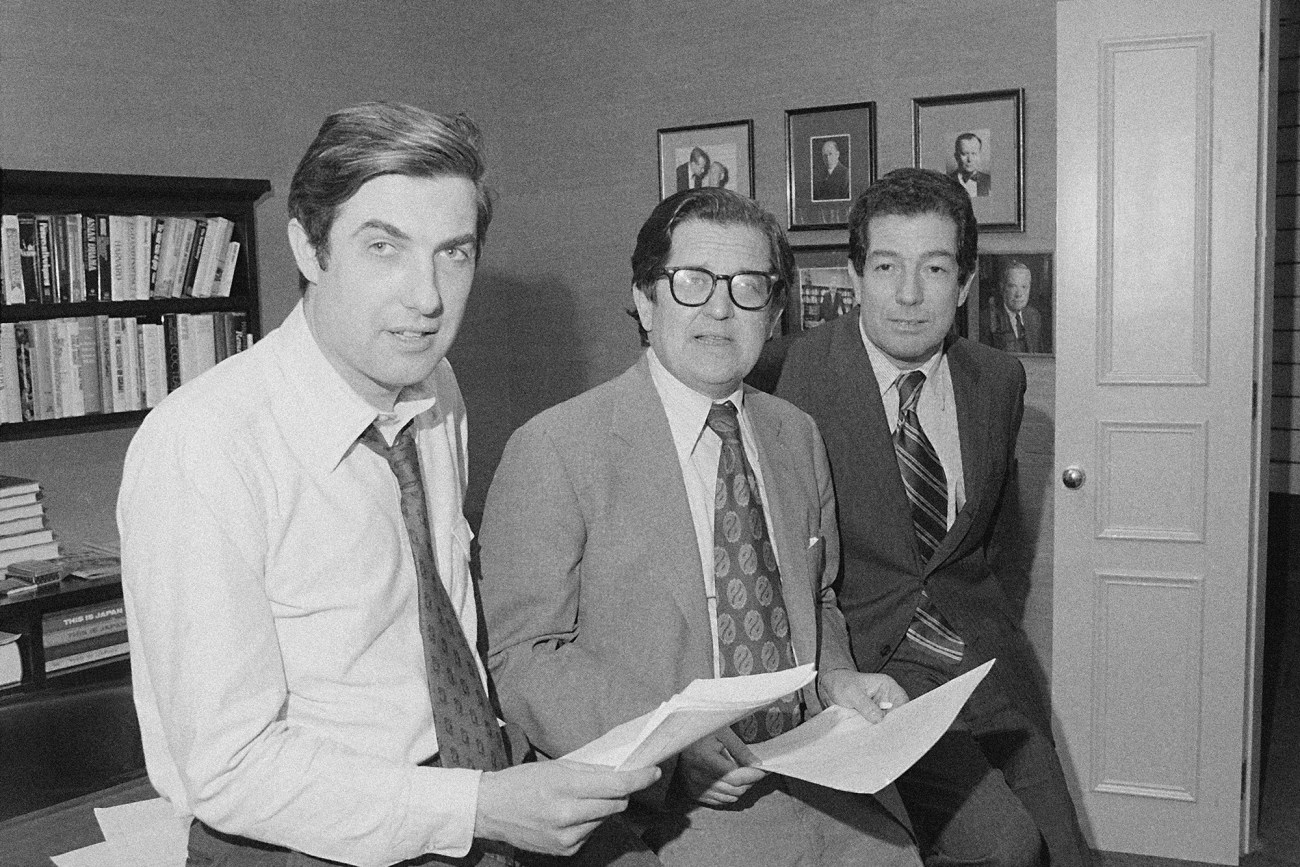

Reporter Neil Sheehan, managing editor A.M. Rosenthal, and foreign news editor James L. Greenfield in an office of the New York Times on May 1, 1972, after it was announced the team had won the Pulitzer Prize for the Pentagon Papers. Sheehan, who obtained and wrote most of the stories about the papers for the Times, was not cited in the award.

John Lent/AP

Sheehan said he believed Ellsberg was fearful of arrest, behaving recklessly, “out of control,” and “just impossible,” strong criticism of a former Marine company commander and top-tier strategic analyst who for months had been risking his safety by squirreling boxes of politically explosive documents he had broken the law by photocopying. The basis for Sheehan’s judgments is hard to discern, since his source’s chief demand was an assurance that the Times would actually use the material. Still, Sheehan proceeded as if he mistrusted his source. He borrowed a key to the Cambridge, Massachusetts, apartment where Ellsberg was storing the Papers, telling Ellsberg he wanted to continue his reading and note-taking while Ellsberg was away. Instead, with the help of his wife, Susan Sheehan, a New Yorker staff writer, Sheehan undertook the very photocopying Ellsberg had forbidden.

It remains a mystery why he did not give Ellsberg the assurance he asked for—that the Times was committed to the story—which Sheehan could have truthfully given. Instead, armed with hard copies of the Papers, a team of Times reporters labored for weeks to assemble an earth-shattering series while Sheehan told Ellsberg, falsely, that the paper’s brass were still trying to decide what they wanted to do. Meanwhile, he made a practice of calling Ellsberg every few days “to try to keep him on the ranch,” he recalled in 2015.

As Ellsberg emailed me when I asked him about the Sheehan interview: “I wasn’t afraid of being arrested eventually, which I’d always (with good reason!) regarded as inevitable. I was obsessed with the fear that the FBI would arrest me before anybody had committed to publishing, getting all my copies! So I didn’t want copies lying around the Times, for someone to report eventually to the FBI, if they had no intention to publish! But the truth was they did already intend to publish…If Neil had simply told me that, I would have given him the hard copies immediately, not merely full access to read them and take verbatim notes. Why he chose not to tell me that, in March [1971] or ever, I never could figure out; and I still can’t.”

According to Ellsberg, a month later Sheehan told him—falsely—that the editors were still dallying but he wanted to have a copy to work with nights and weekends in the meantime. At this point, Ellsberg relented and gave Sheehan a complete copy of the Papers, which, of course, the Times already had.

Sheehan still kept Ellsberg in the dark about the Times’ actual plans. According to Ellsberg’s memoir, he found out only because he was tipped by another Times editor that publication was imminent, and his frantic calls to Sheehan seeking confirmation weren’t returned. As the Sheehan interview notes, when the stories actually began to run on the morning of June 13, 1971, Ellsberg was “blindsided.” Crucially, what Patricia Ellsberg, his wife, called Sheehan’s “monumental duplicity” also left the couple with a full copy of the Papers in their apartment. Fearing that the FBI might now come to their door and stumble on an incriminating trove, he hastily moved the Papers to the home of a friend.

Ellsberg now says, “But it all worked out well, so I had no reproach to make of Neil, ever, except for the failure to tell me on June 12 or before that I shouldn’t have Papers in my apartment because the Times was coming out on the 13th.”

Ellsberg is forgiving, but it’s not at all clear that reproach isn’t warranted. The idea that lying to a trusting and truthful source is among the options in a newsroom’s ethical playbook is ridiculous, and it cannot help but discourage whistleblowers with vital secrets from coming forward. The material a source makes available, which the source may have run serious risk to obtain, is offered to a journalist subject to conditions, and those conditions can be anything but trivial: They may limit how the material is attributed, which portions of it may be used, the steps the news organization may take to authenticate it, or even how it is to be framed. When information comes with conditions that both parties agree to, neither is free to ignore or alter them unilaterally. Nor, as should be obvious, is either party free to agree to them with no intention of honoring them.

Workers in the New York Times composing room look at a proof sheet of a page containing the secret Pentagon report on Vietnam on June 30, 1971.

Marty Lederhandler/AP

All of which makes the Times’ institutionally triumphalist perspective on the affair especially problematic. The story about Sheehan’s recollections was all about the Times’ intrepid heroism and organizational achievement, with nothing from Ellsberg, who astoundingly wasn’t approached for comment; instead, he is casually maligned as reckless and out of control, given no credit for his own courage and determination, and not asked to respond. (In fact, a week after the Sheehan interview was published, the Times ran another article, this one an “insider” piece built on an interview with Janny Scott, the reporter who’d interviewed Sheehan in 2015. Here was the Times running a story about a story about a story—the Pentagon Papers—without once hearing from the person who had made it all happen.) Equally concerning, neither recent story answered, much less asked, the question of whether Sheehan’s editorial bosses knew and approved of the way he dealt with Ellsberg. And finally, the whole matter begged for comment on the critical question of whether lying to sources was ever permissible and, if so, whether it remains permissible under the news organization’s policies. That, too, went unaddressed. I put those questions to the Times and received this reply from Danielle Rhoades Ha, vice president for communications of the New York Times Co.: “These are intriguing historical questions, but we’re not going to try to second-guess the tough decisions made half a century ago by Times journalists handing a monumental story like this.”

We’re also left with the question of why Sheehan insisted that his interview not be published while he was alive. Knowing his reputation for probity, one can only imagine that he remained uncomfortable with the breach of trust his actions constituted. Then again, it may be just as well that this dimension of the story isn’t widely known; ignorance has value too, at least from the perspective of those of us who fear that the treatment of the premier whistleblower in living memory might deter the next generation of whistleblowers. They are an imperiled species, thanks to ever more powerful surveillance technology, zealous prosecution under Republicans and Democrats alike, severe handling by the courts, and a news media that routinely seeks to distance itself from its helpmates once they get in trouble. Whistleblowers will continue to come forward, as they must for all our sakes, only if they can expect to be welcomed into collaborations founded on mutual respect and a shared passion for justice.