Mother Jones; David Corio/Redferns/Getty; Twitter

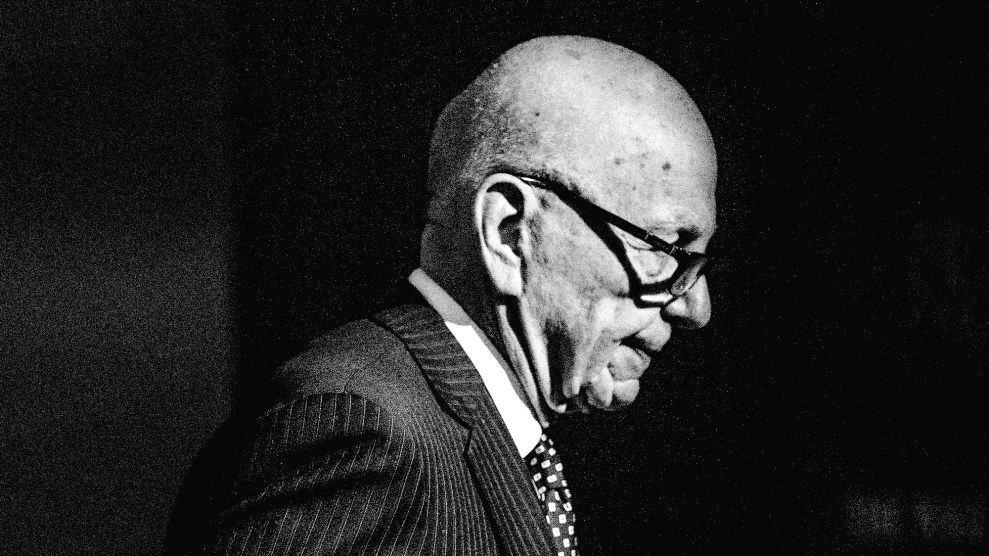

You can’t separate The Fall from the voice and the face of bandleader Mark E. Smith. “You can tell how a trombone sounds by looking at its shape,” Tobi Haslett wrote in a piece on Smith in Artforum, “just as you could see, in the scowl and bitter rictus of Mark E. Smith, the slashing vocal intensity that came pouring out of that face.” Later in his life, Smith’s cheeks were pockmarked, his eyelids drooped, his expression contemptuous. Early photos show his fragile skin a bit too porcelain—his tender, large forehead ill-hidden behind a gash of hair. That face. Mark E. Smith looked like a word he’d spit: Bastard.

To be clear, he was one. Since his death in 2018, ending The Fall for good, in the remembrances that have noted Smith’s litany of crimes that exact word appears regularly. It has a nice, almost old-fashioned ring, giving off the gravel that attracts many to the mythologized northern English band without fully damning Smith for his (another cop-out word) idiosyncrasies. Sasha Frere-Jones has a longer list of nouns—”Troll, syllabist, bandleader, orator, pest, alcoholic, medium, stenographer, record producer, pedant, speed freak, duppy, redeemer, and glorious irritant”—but concludes with a different kind of indictment: “Mark E. Smith was, before anything else, a writer.”

And yet, a musician, a performer. To see Smith’s lyrics divorced from that context, and from him, is impossible. It is even “strange to see them written out,” as Haslett writes, “twitching nakedly on the page severed from his yelp, his bile, his screech, his sneer, his glamorous dysfunction, and ratty button-down shirts.”

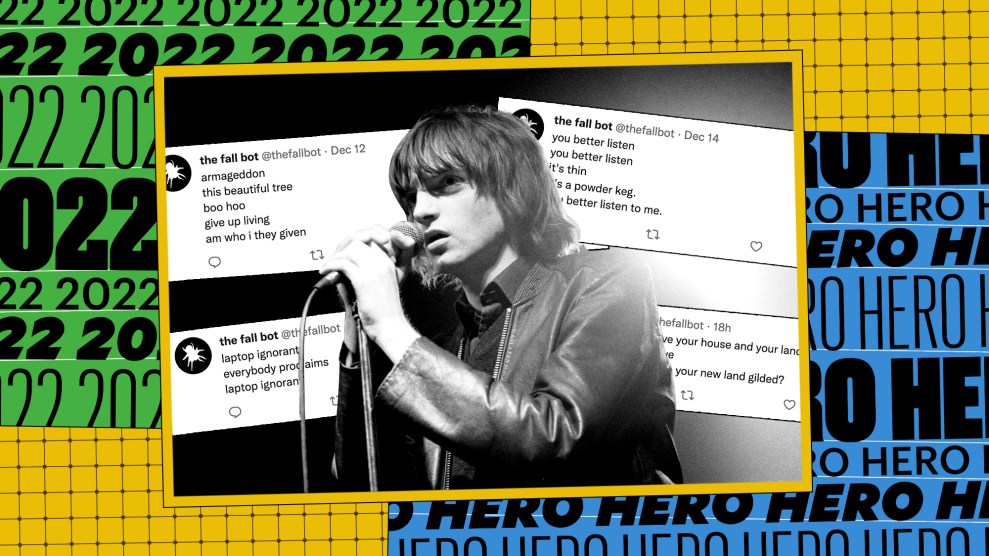

Consider how odd it is to see the writings of Mark E. Smith like this:

do me a favour: cut your lip and shut up

— the fall bot (@thefallbot) December 5, 2022

Still, this year, I delighted in Smith’s words “twitching nakedly”—severed and clipped—when they were posted by an automated Twitter account titled “the fall bot.”

The account is one of many bots that tweet an artist’s opus in snippets. I like the David Berman one, too; the Sylvia Plath food diary is good and popular. Each brings something of the literary world down to our muck. Amid the accounts I follow ostensibly for work—often journalists discussing news or chatting about their lives—I could not help but hear Smith yelling.

It’s a Saturday. Someone has screeched “BREAKING: TK something banal,” and a retweet of “NEWS: Some work,” and then Smith:

the evil is not in extremes— it's in the aftermath

the middle mass after the fact

vulturous in the aftermath— the fall bot (@thefallbot) December 4, 2022

These observations gave me a certain perspective on the necessity of most things. And that is that most things are bullshit. It also helped me appreciate Smith’s writing a bit more. The compacted nature of a tweet shows off some of Smith’s gifts for concision. In a song, it’s sometimes the sustained, murmured irritation that I enjoy. Here, the humor hits harder. It is more like clanging poetry. “I read some of his stuff and think, ‘This is so bloody amazing,'” Kay Carroll, an early member of The Fall, told Vice after Smith’s passing. “He managed to cram so much in one line.”

there's always work in progress

you're always in work in progress— the fall bot (@thefallbot) December 19, 2022

The bot also highlights work I have not heard about much. The Fall’s later albums were often terrible. Smith put out music until his death, but almost everyone knew it was lacking. “A lot of it is just driven by misanthropy,” Smith explained in 2011 of his decades of longevity. I had not heard this little story, for example, about a late-career line from a track called “Irish.” Supposedly after hearing that James Murphy, the lead singer of LCD Soundsystem, adored him (with Murphy even saying early in his career, “The Fall are my Beatles”) Mark E. Smith wrote this:

james murphy is their chief

they show their bollocks when they eat— the fall bot (@thefallbot) November 25, 2022

When asked by Vulture if the lyric was about the same James Murphy, Smith responded: “Ha-ha. What do you think?”

Ah, what’s that word? Bastard?

It’s easy to get heady with The Fall. Smith’s poetry seems to long for an explanation. Half the time you can’t hear it. He sang in a growl over fuzz. The music is ramshackle. This is not a house being built; it is a home collapsing. It is disorder with a pulse. You can convince yourself: People don’t understand, this is important; I have to say something. A lot of writers already have and a lot will.

But I liked how, with the bot, Smith spoke—in a severed way—for himself, amidst a disgusting world.

oswald defence lawyer embraces the scruffed corpse of mark twain

— the fall bot (@thefallbot) December 4, 2022

He would pop up in my life at random; he would enter angrily. And I would have to question myself. Twitter allows constant information. You can see the entire world from your desk. Yet after viewing so much—after seeing a photo of war, the terrors of poverty, news of corruption—what do you do? I usually keep scrolling. And what does that make me? Amenable, agreeable, and wrong.

“Those who dare mix real life with politics / And go on regardless of the discoveries,” Smith once sang. “Will feel the wrath of my bombast!” He yelled at us about what taking this all seriously did to him: “Clanging in my heart. / Bastard!”

As usual, the staff of Mother Jones is rounding up the heroes and monsters of the past year. Find all of 2o22’s here.