Mother Jones; Ashley Landis/AP

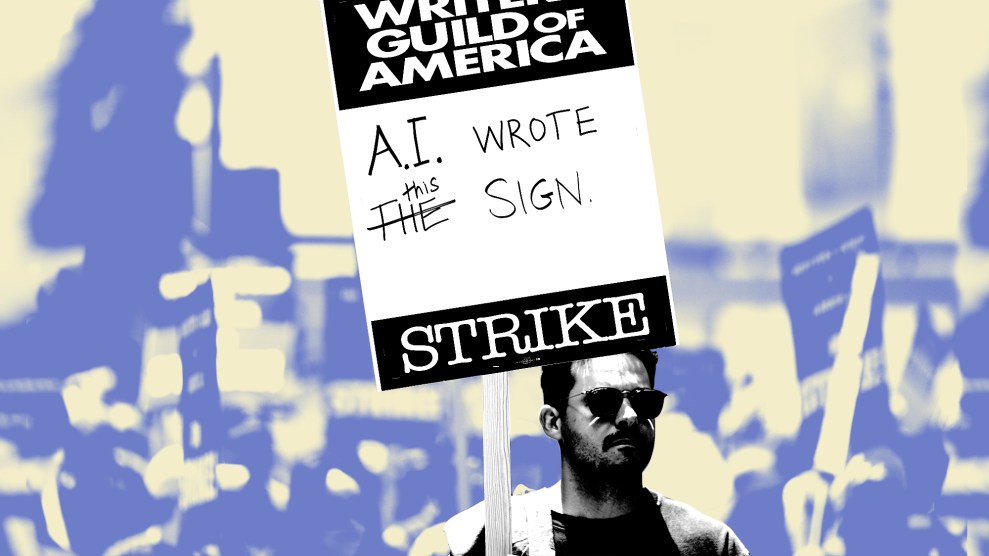

By now you’ve seen the scenes of young and middle-aged Americans wearing cargo shorts and Patagonia Baggies Brimmers in front of movie studios holding ironic picket signs, such as “Chat GPT doesn’t have childhood trauma!” As the battle grinds into its 12th week, with no end in sight—and the actors’ union now part of the strike too—it’s easy to think that a fight between a bunch of “rich Hollywood writers” and the big studios and networks may mean nothing to you, but it’s quite the opposite. This is the labor fight of our generation.

While in the broader labor force, the share of union members has fallen from 34 percent in the 1950s to 10 percent today, Hollywood remains a devout union town. Except for reality TV and some indie films, the majority of all personnel involved in film and TV production are part of organized labor. And tech companies, now dominating the Hollywood landscape, hate that.

Before we dive into why that is, let me explain the life of a Hollywood writer. I got my big break in 2016 when I became a Sundance Institute episodic fellow with a TV pilot I wrote on spec (i.e., without pay). I then partnered with Gina Rodriguez and CBS Studios on that script, and we all went out and sold it to The CW. Luckily, all of these players were also involved in the award-winning show Jane the Virgin, so when showrunner Jennie Snyder Urman was looking for one additional staff writer for her writers’ room, I happened to be at the right place at the right time.

On Jane the Virgin, I learned how a writers’ room worked. I was allowed to shadow a higher-level writer as she produced her episode of the series, on set and on location. Eventually, I found myself on set, producing my own episode. And once I hit a certain level of earnings, I qualified for the Producer-Writers Guild of America Pension & Health Plans.

That is how TV work used to function for writers. But little did I know that my experience was already becoming the exception.

Other writers from my Sundance class went on to successful careers, but most have never visited a set to learn how to produce the episodes they wrote. While CBS ordered up 22-episode seasons for Jane the Virgin, my peers were writing shows with eight- or 10-episode arcs. My room was populated with 12 to 14 writers; theirs had half that many if they were lucky. I was making a decent living; they were scraping by. Why? Simple. I was working in broadcast television, and they were in streaming.

The difference between the two is why the Writers Guild of America is on strike.

Broadcast shows are aired on the networks we watch for free—CBS, NBC, ABC, The CW, Univision, and so on—because they are supported by advertisers. If a broadcast show becomes a hit, the network orders up more episodes. The show stays on the air longer, and its creators participate in its success.

Streaming, which was originally introduced to the entertainment industry by tech companies, is not like that. The business model for Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, and Apple TV is simple: get more subscribers. And the way to do that is through new shows. Rather than ordering one show with 20 episodes, streamers order two shows with 10 episodes each. And instead of renewing a hit show, streamers cancel it the second they think they’ve squeezed all the potential new subscribers from it. More importantly, streamers never share their data, so writers can’t know if they’re being underpaid for the most successful show in the world or overpaid for the biggest flop in the streamer’s history. (Spoiler alert: It’s the former.)

Then there’s the matter of residuals, the payments we get when shows go into reruns. My union, the WGA, negotiated the first TV residual provisions in 1953. I receive residuals each time my episode of Jane the Virgin re-airs.

But the tech companies have disrupted this system. As Variety pointed out a few months ago, the most popular movie on Netflix in January 2022 was Don’t Look Up. But the second most popular was Adam Sandler’s 2011 film Just Go With It, then new on the service. Yet writer Timothy Dowling saw barely any residuals.

Writers who worked on procedurals for broadcast used to make somewhere around $20,000 per residual check. Now they are writing the same type of show for streamers making in the ballpark of $150 per residual check. Residual checks are how writers pay their rent and provide for their families when they’re between shows or working on their own shows. This is money we earned, money our union negotiated for us 70 years ago.

Which brings us to the core of every writer’s frustration. We’ve already had these fights. We had them over half a century ago, and in that time, studios and broadcasters have made an obscene amount of money under the rules they negotiated with our union. But now the tech and digital entertainment giants, the new kids on the block, are trying to throw out all the rules.

That’s why this fight is part of the labor story of our generation: tech companies destroying the power of labor in any industry they enter. The convenience of Spotify, Uber, and Airbnb has come on the backs of workers in the music industry, the taxi industry, and the hotel industry.

But in Hollywood, the tech companies have encountered something new. Something they weren’t used to: a strong union. One that saw what happened to workers in those other sectors and is not about to just let it happen again.

Writers are the opposite of what you think of when you envision a union worker. We’re not rugged, we’re neurotic. Our carpal tunnel doesn’t come from lifting heavy things, but from typing too much. But like every other union member in this country, we are overcaffeinated, we know our worth, and we refuse to be exploited.

TV writing has never been riskier. That is why we are fighting for the end of the mini writers’ rooms that are now the norm due to streamers; the end of not paying writers for covering set (i.e., being paid to produce the episodes we wrote); the end of shrinking earnings; and a ban on artificial intelligence (AI) as a tool to generate scripts.

This one here is a big freakin’ deal. In a future where AI is more cost-effective than hiring a writer, a room of 10 writers could soon become a room of one writer and a box with AI software. Which, to be clear, is simply plagiarism on steroids.

Already, the entertainment companies are looking to cheaper content, such as nonscripted and reality shows, to replace our labor. And if you don’t think that’s a concern, remember that in the writers’ strike of 1988, the studios created Cops; in the writers’ strike of 2007, the studios created Celebrity Apprentice with Donald Trump. We know the lasting consequences for race relations and politics.

The fight against AI replacing human creativity, against tech turning yet another industry into a gig economy, is existential for us writers. But it is for so many other workers as well. Nothing has moved me more during this battle than the words of Alex Aguilar, principal officer of LiUNA Local 724—the laborers of Hollywood who support the carpenters, painters, electricians, plumbers, plasterers, sheet metal workers, and other crafts in TV and film production—when he told an auditorium filled with more than 2,000 writers’ union members, “We will stand with you, we will stand behind, and if we have to, we will stand in front of you.” Because of this kind of solidarity from our sister unions in Hollywood, writers and actors are determined to remain on strike for as long as it takes. As the writers’ guild negotiating committee pointed out, the survival of our profession is at stake in these negotiations.

On the picket line, I’ve heard people scream at us to go back to work, police officers reprimand us for being too loud, and in one case, a white dude yelling, “Illegals are going to take your jobs!” But these outliers are washed out by the loud honks of support. The honks don’t usually come from the expensive Teslas that drive by. They come from the bus drivers, the electrical trucks, the waste workers, the big rigs—from the other union workers in the City of Angels.

Rafael Agustin, a member of Mother Jones’ board of directors, was a writer on the award-winning CW show Jane the Virgin and is the author of the bestselling memoir Illegally Yours.