In a matter of hours, Marianne Williamson will take the stage in cascading taupe and have 1,000 disciples eating out of her delicate hands. She will ask them to pray for peace, for prosperity, for the deliverance of a prostitute. She will urge them to save America from spiritual bankruptcy, and they will nod and murmur and consider her call to action. A young man will stand to ask advice about a friend and sit down smiling after she proclaims his attitude “enabling.”

She will hold the lecture at Los Angeles’ Wilshire Ebell Theater, where she is a frequent headliner. But right now, the wildly popular feel-good guru is tucked in the corner of a couch, and the voice that can be as seductive as a clear stream is gaining force and intensity. First one finger starts wagging, then both nicely muscled arms are in the air. Williamson doesn’t like questions about her power as a priestess of the New Age, doesn’t much like being questioned about her path to enlightenment. Skepticism is met with run-on sentences, cynicism with a silent stare. “Laugh at all of this at your emotional peril,” she warns in her 1993 book A Woman’s Worth, which spent 19 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list.

“See, I find it interesting. I find that I’m in the only career that I know of [where] the more successful you are, the more suspicious you are,” the 45-year-old Williamson says. “Like I have these slavish followers. In any other field, if you’ve got a large audience, people would say you must be good at it. I have an audience. Barbra Streisand has an audience. I don’t have followers.”

Maybe so. But the millions of people who buy Williamson’s books and cassettes, the thousands who attend her monthly lectures on love, relationships, or whatever is on her mind, speak of her with an adoration bordering on worship. Those who “get” her, revere her. At her behest, they clasp hands with the strangers seated beside them. They close their eyes in meditation, leaving purses and packages unattended. On the eve of the Fourth of July, they sing “God Bless America,” and they do it in key. They sign up for her tape-of-the-month club; scan her Web site (www.marianne.com); and make religious pilgrimages with her to India, Stonehenge, and Ireland. As Jim Muccione, a college administrator and devotee, explains before one of Williamson’s summer lectures in her home base of Los Angeles, “She’s a warrior of the heart — I’m the pilgrim, and I consider her a teacher.”

Not everyone, of course, gets Williamson. Skeptics wonder what her motive is, though all she seems to ask is that people pray and love and buy a book or tape or two. They suggest that she’s only in it for the money, but then Williamson turns around and lets in for free anyone who can’t afford the suggested donation for her New York and Los Angeles lectures. Or she gets her big-bucks friends to donate to her charities, such as Project Angel Food, which provides meals to people living with HIV and AIDS. She’s an evangelical, to be sure, but also an unembarrassed political liberal whose latest book, The Healing of America, warns that spirituality can unite the country while politics steeped in religion can only divide it. Clearly hers is another case of the messenger being more complicated than the message.

“Because there’s a disconnection inside people, there is no listening,” Williamson says. “The reason that there are no major voices for social justice today is the listening isn’t there. We have to address it because people’s hearts aren’t open enough to hear. Do you understand what I’m saying?” In fact, much of what Williamson says makes perfect sense. She’s affirming the obvious, and even she concedes that most of it has been said before. She’s only paraphrasing for a postmodern world, fluttering around the margins of faith without forcing anyone to examine the core.

“Because there’s a disconnection inside people, there is no listening,” Williamson says. “The reason that there are no major voices for social justice today is the listening isn’t there. We have to address it because people’s hearts aren’t open enough to hear. Do you understand what I’m saying?” In fact, much of what Williamson says makes perfect sense. She’s affirming the obvious, and even she concedes that most of it has been said before. She’s only paraphrasing for a postmodern world, fluttering around the margins of faith without forcing anyone to examine the core.

Williamson’s first book was the 1992 A Return to Love, which sold 750,000 copies in hardback, an equal number in paperback, and spent 39 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list. The book even won her a coveted on-air chat with Oprah Winfrey. A Return to Love was Williamson’s interpretation of the much deeper, more demanding A Course in Miracles, which Williamson describes as a “self-study program of spiritual psychotherapy.” Written by psychologist Helen Schucman between 1965 and 1972, the three-volume Course bills itself as a correction to Christianity — beginning from a premise of original innocence rather than one of original sin, for example, and focusing on the metaphysics of identity and ego formation. Schucman, who died in 1981, said that Jesus had dictated the books to her. At first, Williamson was turned off by Course‘s heavy emphasis on Christianity. But she ultimately reconciled it with her Jewish upbringing, and the woman who had written a Dear John letter to God as a Texas schoolgirl says she found her way free of “terrible emotional pain,” eventually even becoming Course‘s public face.

Williamson, who says she was “very prayerful” as a child and who now writes rambling prayers about spiritual issues off the top of her head for any and every occasion, has won both a Hollywood and a homespun audience by personalizing the spiritual underpinnings of A Course in Miracles with anecdotes from her own life; breakups, breakdowns, she shares it all. A single mother with a 7-year-old daughter, she has a “been there, done that” honesty about her — talking about everything from abusing drugs to hard drinking to unsuccessful relationships. She was, in her own words, a “total mess” in her mid-20s. She picked up A Course in Miracles in 1977, put the books back down, and spent another year in misery before she found her way back to them. She tells fans that she was one of them, is one of them. Like her, they believe, although it is difficult to decipher what they believe in beyond their own right to be happy and carefree.

Offering religion without rules, salvation without sacrifice, the former cabaret singer has remade herself into the perfect priestess for a culture steeped in pop. “Love conquers all” is no cliché to Williamson and her readers. Focus on feelings, she reiterates in book after book, and the rest will follow — from a good man to a great salary to a God-fearing nation. Forget the fuss and muss associated with actual effort.

As with many New Age programs, the particulars are not as important as the intent, and that may be part of Williamson’s appeal. She doesn’t demand critical thinking. Never mind, for instance, the centuries of religious history that separate Jews like her from Christians. Sure, Jesus was the son of God, she says, but then so are you and you and you. All of us have messianic potential. Williamson makes the holy hospitable, and she has made the ultimate truth relative as well as negotiable.

“You know the Jews say the Messiah is coming and the Christians say the Messiah came and Einstein said there is no time,” she says. “So this whole idea he’s coming, he came — I think we’re living in a time where the official take on Jesus is not particularly relevant to me.”

Says Gary Kain, a psychotherapist who describes himself as a “semi-fan” who turns out for a half-dozen of Williamson’s lectures a year, “I don’t like organized religion, and this helps me highlight the spiritual part of my life. But it was a turnoff when I first came because there were a lot of actors here. There’s a lot of ‘this is the place to be.'”

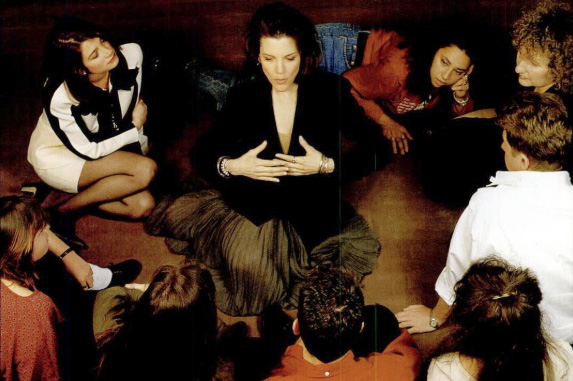

By preaching peace and love, Williamson herself has become a celebrity of sorts, going from small prayer circles to the stages of auditoriums seating thousands. She was at the altar blessing Elizabeth Taylor’s last failed marriage. She was invited to the White House to share her thoughts with Hillary Clinton. As a result, she is in the awkward position of promoting emotional accessibility while hiring handlers to keep unpleasantness away. Publicists want to know in advance what Williamson will be asked. An agent refuses to provide sales figures for her books and cassettes, arguing that the figures are proprietary. She too can be elusive, or at least more circumspect than her books would indicate. Williamson says she never considered what The Healing of America might accomplish, for example, and she is reluctant to address the impact she has had on so many Americans.

But the truth is that The Healing of America is a daring departure for Williamson, even if she says it is merely an extension of her belief that love and prayer will save individuals and maybe even the world. The hefty manuscript almost — but not quite — dares to state that navel gazing alone is not enough; that it’s time to move from self-absorbed me-ism to a more civic-minded we-ism. This message runs the real risk of turning off an audience that appears to be looking for easy answers to earthly salvation. Williamson says that doesn’t matter. She says she wrote the book her father would have wanted her to write, and that she doesn’t know who will buy it and doesn’t care. It’s time, she insists, to put the yang back into yin-yang by rededicating ourselves to citizenship.

“An angry generation will not bring peace to the world, I do believe that,” Williamson says, flitting her birdlike limbs again. “Everything that you do is infused with the energy with which you do it. I don’t think ultimately the issue is: Do you work on yourself, or do you work on the world? Because ultimately there is no separation between the two. A lot of the toughest-minded people in America need some personal rehab. But some of the people who have been working on their hearts need to read a book or two. That’s my point.”

Later, she calls to clarify. Her previous three books, after all, were not intended as a push toward greater responsibility to the world at large (although her 1994 book, Illuminata, did prove ahead of its time, offering up a prayer of atonement for the country’s treatment of African Americans long before President Clinton began calling for a dialogue on race). “Self-awareness is not self-centeredness and spirituality is not narcissism,” she says. “Know thyself is not a narcissistic pursuit.”

But it is in step with today’s search for self and spirituality. As Robert Ellwood, a professor of religion at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles explains, the New Age movement offers a sort of build-your-own-religion kit, a way to pick and choose the rules, keeping the convenient precepts while discarding the cumbersome ones. The goal is swift gratification — the same impulse, he says, that causes people to switch jobs or spouses the instant they are unhappy.

“Part of the mood in contemporary society is basically the idea that absolute consistency is not necessarily a top priority in finding meaning and fulfillment in one’s life,” says Ellwood, author of The Sixties Spiritual Awakening and The Fifties Spiritual Marketplace. “People say experience as much as you can, that that’s what matters. The important thing is one’s own path to fulfillment.”

Williamson herself values intellect as much as instinct. “I think I’m a mix,” she offers. “I’m a provocateur. I come into a situation where I don’t particularly relate to any of the institutionalized boxes. I’m not a minister, I’m not a rabbi, but I’m totally excited by God and Jesus. So you get this Jewish girl talking about Jesus — it’s going to get attention. It’s a juxtaposition that is perhaps interesting. It’s similar to what I say about politics in The Healing of America. It’s the same with religion. One group says it’s this way, another group says it’s that way, and a lot of people are feeling that, you know, ‘deep in my heart I don’t feel it’s either way.’ Well, neither do I.”

She laughs, a throaty, theatrical laugh: “I don’t think I represent some new category. I think I do represent kind of a freethinker.”

Williamson wants to be an accessible freethinker, and she falls back on language familiar to anyone who has ever read a self-help book. Much of her writing is intentionally easy to digest, if hyperbolic and given to psychobabble. “We are tyrannized by a belief that we are inadequate. No Nazi with a machine gun could be a more tormenting presence,” she says in A Woman’s Worth. The bottom line, according to this particular book, is that all women must overcome the damage done by dad’s indifference, while still retaining their femininity. A Return to Love, on the other hand, offers the miracle as mindset: Pray hard enough, release those negative thoughts, and anything can happen. She writes, for example, that she met up with a doctor in a bar just as she was nursing a sore throat and worrying about how she’d manage that evening’s lecture.

“She’s a real combination of the mystical and the popular self-help wisdom,” says Don Thompson, who has been helping Williamson set up for her lectures since the days when her fans barely filled the front rows. “She has a way of connecting with people in a remarkable way.”

Williamson’s supporters, and obviously they are plentiful, say that her beauty transcends the physical, that the work she has done inside is what is shining through. Early on, for instance, when AIDS was only beginning to emerge as a devastating killer, she was ministering to dying men. On this night, at her Ebell Theater lecture, she’s made sure the lobby is filled with fliers listing the local hospices that need volunteers. She takes time with each audience member who has a problem, no matter how trivial.

“I’ve always been the first to say that spiritual seeking without service is self-indulgent,” she says. “I think the question is: Dear God, how can I serve? Not that I’m trying to figure out what someone needs…. I am saying we don’t have the time on this planet to wait until we’re more spiritually evolved to check out what’s going on in this country.” Appendix A to The Healing of America is called “Resources for Activism.” Appendix B consists of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

Later that night, as people wander back into the theater after the break, newly purchased books and tapes in hand, a dozen or more say they are open to wherever Williamson wants to lead them. Still, a third of the crowd skips the second half of the lecture, perhaps turned off by the political rhetoric, perhaps impatient with the emphasis on something other than themselves. Williamson and the remaining audience will pray for them anyway.

Lynda Gorov is the Los Angeles bureau chief for the Boston Globe.