Photo: Brian Dobin

Most Americans never venture into the hills east of Sheridan, Wyoming. The highway to Yellowstone and the Tetons doesn’t go that way, and once you head east of Sheridan, you come into a country that used to turn roadless pretty quickly. Its drama is its emptiness, its subtle beauty, its ability to sustain itself and the plants and animals that live upon it. To an outsider, the landscape may look simple, but it’s really a complex maze of draws and arroyos and interconnected natural drainages, places where water might linger after a prairie storm, giving life to a late-summer flourish of grass, or where it might rush away in tumult, down into the Powder River or the Tongue.

I didn’t expect these hills to look their best. They were in their third consecutive summer of drought. The drought was one thing — a part of nature, after all, no matter how bitter its toll. But in the hills above the Tongue River, where mixed-grass prairie had once intermingled with sagebrush steppe, some sections of the landscape looked like an industrial zone. Roads trailed off in every direction, each one ending at a wellpad or a compressor station or a storage site or a collection of stakes marking future pads and stations and sites. The county roads had been widened and covered in scoria to accommodate heavy truck traffic. Pale new dirt roads cut off across the hillsides and through the sunburned grass and sage, some gated and locked, a reminder that this was now a territory under occupation by men who had leased what lay under the landscape and to whom the landscape itself was largely an impediment.

In Wyoming, coalbed methane fever has struck. To energy companies, the attraction of coalbed methane is enormous. Getting to the methane usually takes little more than a shallow, relatively inexpensive water well. When water is pumped out of the coal seams underground, the methane is freed from the seams and flows through natural fractures in the coal, called cleats, and up the wellbore. Sometimes drillers inject a high-pressure compound of sand and toxic chemicals, called fracing fluid, to fracture the coal and allow the methane to flow more easily. At the surface the water is discharged and the gas is collected, piped to pod stations, and metered. Then the methane is compressed three times before it’s piped away to its ultimate market, where it becomes an integral part of the Bush-Cheney National Energy Plan.

Until recently, there wasn’t much incentive to produce coalbed methane (CBM) commercially. It was considered a nuisance — a danger in mines, where it sometimes exploded, a greenhouse-gas pollutant in the open atmosphere. But a 1980 tax credit called Section 29, intended to promote the development of alternative fuels, made CBM look promising. When natural gas prices spiked in 2000, in part because of energy price manipulation by companies like Enron, CBM began to look downright intoxicating. Prices for methane have fallen sharply since that peak, but luckily for producers, an administration hell-bent on extractive industries has been elected. Once in office, the Bush administration instructed the departments and agencies that regulate energy production to speed up the approval of CBM leases, and President Bush appointed former CBM industry lobbyists to critical positions in the Interior Department.

What’s happened in Wyoming since is “the biggest gas play in the lower 48,” as some people call it. Methane companies have been snapping up mineral leases and drilling at a furious pace. If the rush were only near established coal-mining towns like Gillette, this wouldn’t be such a problem. But what makes the methane boom controversial is that coalbed methane is found wherever there is subterranean coal, even in noncommercial quantities. It lies beneath rangeland and national forests, beneath hay ground and retirement communities, beneath wildland and grazed land.

The CBM industry is already well established in some of the West’s most important coal basins, including the San Juan Basin in northern New Mexico and southern

Colorado, and the Unita Basin in eastern Utah. But the biggest prize is the Powder River Basin, 9.1 million acres of largely pristine rangeland anchored by Gillette but reaching westward — well out of coal-mining country — to the base of the Bighorn Mountains, near Sheridan, and arcing northward across the Montana line. By the end of the decade, the Bush administration plans to drill an estimated 70,000 wells in the Powder River Basin, which will require at least 32,700 miles of new roads as well as 73,000 miles of new pipelines and power lines. There are already some 14,200 wells in the Wyoming part of the basin. When all the Wyoming wells, 51,000 of them, begin to operate, they will suck as much as a billion gallons of water out of the earth every day. The wells will deplete aquifers and, in some cases, dump salt-laden water on land that is particularly ill-suited to handle it, ultimately altering the hydrology of the rivers in-to which that discharge water makes its way.

The CBM boom has not gone unopposed. Two Wyoming environmental organizations, the Powder River Basin Resource Council and the Wyoming Outdoor Council, have challenged the legality of several leases held by Marathon Oil, one of the largest methane operators in the state, and their suit has been upheld by the Department of Interior’s Board of Land Appeals. Montana has declared a temporary moratorium on CBM development until its environmental impact has been more carefully assessed. Many Montanans know exactly why they’re worried. The rivers in the Powder River Basin, now potentially laden with saline water, flow north into Montana.

In May, the regional office of the Environmental Protection Agency gave an “environmentally unsatisfactory” rating to the Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) draft environmental-impact statement for the Powder River Basin CBM project. Such a rating indicates that the BLM violated the National Environmental Policy Act, a cornerstone the nation’s environmental laws. Among other concerns, the epa noted that the BLM’s project would violate state clean-water and perhaps clean-air requirements, that it could render river water “unsuitable for irrigation” and cause “irreversible impact to soils.”

In response, Wyoming’s governor, Jim Geringer, wrote to EPA administrator Christie Whitman, complaining that her agency had commented too critically on the Powder River Basin plans. Steven Griles, deputy secretary of the Interior, also complained in a memo that the EPA rating would “impede the ability to move forward in a constructive manner.” Griles is a former methane-industry lobbyist. Among his former clients is Devon Energy Corp., one of the largest CBM firms working in Montana and Wyoming.

What opponents of CBM are up against is simple: an entrenched energy lobby, and the local and national impact of the cash flow that comes with the gas flow. The BLM estimates that if the methane reserves in the Wyoming portion of the Powder River Basin were fully developed, the federal government would receive some $3.1 billion in royalties over the next 10 years. The state of Wyoming would receive $462 million in royalties, as well as some $2.5 billion in taxes. Campbell County would take in some $1.5 billion over the same period, while Sheridan County would receive $443 million. Payrolls and personal income in the region would rise accordingly. No one even bothers to estimate how much the energy companies would make.

The idea of methane is usually sold to consumers in phrases like “energy independence” and “national security.” But despite the effort to rationalize this gas rush, it’s nothing more than a rush to pump dollars out of the ground as fast as possible. For there is one underlying fact that makes a mockery of the methane boom: If all the coalbed methane were extracted from economi-cally significant reserves in the Wyoming portion of the Powder River Basin — between 16 and 25 trillion cubic feet — it would yield only one year’s supply of natural gas for domestic use.

Methane is also routinely touted as a source of “clean energy,” and at the point where it is being burned, it is indeed cleaner than the coal being shipped from Gillette to fuel electric plants across the country. Eric Barlow is a veterinarian who lives on a ranch west of Gillette. He and his family have decided not to allow CBM development on the portion of their ranch where they control the minerals. As Barlow puts it, “The gas companies love to show that clean blue flame.” But to burn methane — to get to that clean blue flame — you have to extract it. And there’s nothing clean about that.

Begin with the land, if only because the outrage nearly always begins with the land. In the American West, land has two legal histories. Under various homesteading acts, the federal government granted farmers and ranchers rights to the “surface estate” of the land they settled, but reserved for itself the rights to the minerals below the surface, called the “mineral estate.”

Sometimes, an owner is lucky enough to own both the surface and mineral estates. But such owners can legally retain a share of the mineral rights even after they sell the property. So while the surface estate may remain intact as it passes from one owner to the next, the mineral estate generally gets divided into smaller and smaller fractions of ownership. A property owner may own the surface of his land without also owning the right to the minerals beneath it, including gas, oil, and coalbed methane. This is a common situation, called “split estate,” across the West.

In Wyoming’s Powder River Basin, 77 percent of the surface estate is privately owned, but 54 percent of the mineral estate is still owned by the federal government. You’d think that federal ownership of the minerals under your property would provide some safeguard against intrusion and inappropriate exploitation. But the mineral estate is maintained by the BLM, which is responsible for leasing out the right to extract minerals to energy companies. And when it came time for the bureau to assess the impact of coalbed methane development, it made little effort, according to the EPA, to study the potentially disastrous environmental consequences.

According to common law, the mineral estate is dominant, meaning that a surface owner can’t prevent the owner of a mineral lease from entering his land to gain access to the company’s subsurface property. With no consent from a landowner, an energy company can explore, drill test wells, and build the entire infrastructure — compressor stations, wellpads, roads, reservoirs, pipe-lines, storage sites — needed to exploit its mineral assets. All a drilling operator needs to do is post a small bond toward reclamation costs and pay a small annual rental fee per wellpad. If a landowner refuses entry, the operator can begin condemnation proceedings. “I’ve sat in on dozens of these negotiations,” Eric Barlow told me, “and the methane companies’ attitude is ‘Take it or leave it.’ They own the first right.” This has left a lot of property owners on split-estate land across the West wondering what exactly they own.

You need to imagine the scene to grasp it. One morning, a man shows up at your front door. You may be a rancher with 10,000 acres near Leiter or a new retiree just settling onto a 40-acre spread on the outskirts of Sheridan. The man at the door tells you he owns a lease to the mineral rights under your land, that his company has filed a bond to cover reclamation costs, and that he and his men intend to begin drilling. Just how it becomes clear that you have no say in the matter depends on the man standing at the door. There have been as many as 75 methane companies at work in the Powder River Basin over the past few years, most of them small. Some are courteous and circumspect, others sloppy and belligerent. There’s a little room for negotiation, but usually only about the rental fee and reclamation costs the company will eventually pay for the damage it does to your land. If the man at the door holds a legal lease to develop the mineral rights under your land — no matter whether his company obtained the lease from a BLM auction or from private mineral owners — all you can really do is stand by and watch when the trucks finally arrive and the bulldozer comes down the ramp. It makes no difference what plans you had for the land. They come second to the plans the lease owner has.

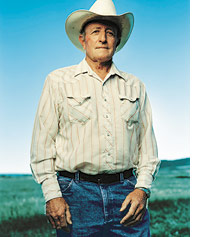

This is exactly what happened to Buck and Mary Brannaman, who own a small ranch south of Sheridan. “They showed up,” Buck Brannaman told me, “dropped the blade on a D9 Cat, and went right up the hill, pushing topsoil out of the way like it was snow.” It was a swift, brutal education in the mechanics of coalbed methane extraction. Methane wells are dug by truck-mounted rigs, but in most cases, of course, the wells are dug where there are no roads. So the crews cut roads to the site of each well, slicing across pastures and fence lines, paying no regard to the contours of the land. The Brannaman ranch lies in a knot of grassy hills. As winter came and went, and the bulldozer came and went with it, the main access roads turned into deep trenches, sluicing runoff and causing serious erosion. The crew cut enormous gouges into the sides of the hills for the wellpads, dumping the topsoil down the slope. They dug ten of the projected thirteen wells; then the crew capped the wells and packed up and pulled out, having done just enough exploration, Brannaman suggests, to hold on to the mineral lease. If the crew had been working on federal land, they would have been subject to close technical oversight and serious restrictions on how they managed their development. But not on private land.

I sat one afternoon with Brannaman, who is a well-known horse trainer and an old friend, during a pause in one of his training clinics. I said that it seemed to me that the nature of coalbed methane development might eat away at the conservatism of many Wyoming residents, more than a few of whom haven’t thought kindly of environmentalists in the past. “You’re talking about me,” Brannaman said. “It’s happening to me right now.”

I’d just driven over the web of new, unwanted roads on his ranch. The drilling company had filled in the worst of the trench roads, but not until the Brannamans filed a lawsuit for reclamation costs, including loss of income and devaluation of property. But the damage was incalculable. There had once been only an old rutted road running up onto the highest reaches of the Brannamans’ ranch. You could get on a horse at the riding barn, on the southern edge of the property, and ride across grassland interrupted only by a fence line. In other words, you left almost everything behind at the very first gate except for wind and grass. The purity of that — and it’s a purity that virtually defines the attraction of the Powder River Basin — is invaluable. It’s a purity synonymous with the American West, the basis for the economic value that ranchers place on the land and the basis for its ecological and recreational value too. Brannaman told me that, thanks to the drilling, he was running only a third the number of steers he had in previous years, less than a hundred. There was no knowing how many other creatures — pronghorn antelope and mule deer among them — had abandoned the premises.

Now, wherever you rode on the Brannaman ranch, you were never out of sight of an ugly red road and the ugly red spurs that came off of it. You’d ride over a rise and into a storage yard full of pipe and conduit. You’d follow the line of a hillside and find it interrupted by great gouges carved out of the land to make room for methane wells that hadn’t even been brought on-line before the drilling crew pulled out. Not a cubic foot of gas had been pumped out of the wells. The compressor station that would compress the methane, roaring day and night with a cataclysmic roar, and the pipeline that would transport it across country hadn’t yet been built. All this damage, and the project had only begun.

But even ranchers who favor coalbed methane development, and who own their mineral rights, are still troubled by the problem of water. From a ridgeline in the hills east of Sheridan, perhaps 30 miles from the Brannaman ranch, I could look to the north and see the green riparian zone along the Tongue River. To the south, across former grassland, I could look out over the web of CBM development, now mostly bare ground that could no longer withstand erosion. It was a good place to think about the inevitable by-product of methane extraction: water. You can’t extract coalbed methane without extracting water because the methane won’t flow unless the water flows first. In the semi-arid West, water is the most precious resource there is, but it’s precious in the sense that no one has put a price on it yet. There are no commodities markets for subterranean water yet, no windfall profits to be taxed. But it’s easy to put a dollar price on natural gas, and in the contest between two resources, the one with a ready market always wins.

When the Wyoming wells in the Powder River project all begin pumping, they will draw a billion gallons of water out of the ground every day. It would be one thing if the water were sweet and the soil in this basin drained easily, allowing the water to replenish the aquifer it’s drawn from. But the water usually isn’t sweet but salty, and the soil usually doesn’t drain well. As Tom Darin, a lawyer for the Wyoming Outdoor Council, has written, “Each drop of water that is withdrawn and discharged onto the ground surface simultaneously depletes the region’s aquifers.” CBM development extracts water that will, by the most conservative estimates, take centuries to replace. The premise of coalbed methane is throwing away the gold to get to the silver.

From where I stood, I tried to imagine where the average of 21,000 gallons of water per day per well might go. The obvious answer — and the inevitable one — is down the draws and into the Tongue River. There were visible efforts to prevent that from happening. Here and there, men on enormous machines had dug containment ponds into the natural drainages or into the sides of hills. Some of the impoundments were lined with plastic, which flapped over the edge of the dirt embankment like a garbage bag inside a trash can. Most of the ponds were empty, but a few contained silty water the color of scraped earth.

On other hillsides enormous sprinklers sprayed water from CBM wells out over the ground. The soil had been rubbed raw and then lightly tilled and seeded in the hope that a crop of some kind might grow there. Despite the profusion of water, the fields were mostly bare. What plants there were looked sparse and stunted, a forlorn green stubble. Some fields in the distance were covered in white dust, gypsum that had been spread over the ground in an experimental attempt to neutralize the effect of the water being sprayed on the fields. Water doesn’t usually need to be neutralized before it’s used for irrigation. But the water that comes out of most CBM wells has a ratio of dissolved salts well above the threshold where soil and plant productivity fall off. “It’s not that bad a water for some uses,” Eric Barlow said. “But I don’t believe in wasting something just because you have a lot of it.” If the water were better in quality, it would only make the waste seem more extreme.

To the industry, of course, coalbed methane looks like nothing but good news. If there’s a spill at a well site, water hits the ground, not crude oil. It requires no open-pit mines, and the task of keeping the public from seeing the true environmental costs of methane, and what a meager source of energy it is, has gone pretty well so far. On regulatory and environmental matters, the industry has more or less had its own way, and the Bush administration clearly leans heavily in its favor. “The methane companies lease the right to produce the minerals,” Barlow said. “But they don’t own the minerals. The federal government does. You and I do. The federal government could step up and take a bigger role in overseeing this.” Under this administration, that isn’t likely to happen. If there’s a public debate on energy at the moment, it is merely about what kinds of energy to develop. “Conservation,” Vice President Cheney famously remarked, “may be a sign of personal virtue, but it is not a sufficient basis for a sound, comprehensive energy policy.” But the fact remains that it would be vastly cheaper, more efficient, and less environmentally destructive for Americans to conserve 25 trillion cubic feet of natural gas by the end of this decade than to extract it from the fragile ecosystem of the Powder River Basin.

Drive across the basin as it is now, and you sense just how fragile it really is. West of Gillette, you come across a patch of small methane-well housings painted a visually benign tan, fenced in by small tan corrals. Then open, uninterrupted rangeland. In the hills east of Sheridan, you drive along hay meadows and sagebrush steppe and then suddenly find yourself in a pocket of methane development, where the crews are barreling down the dusty roads and a new compressor station roars like a jet all night long. On the highway from Buffalo to Ucross, you start counting the roads that have been built in the last three years, the wellpads on the hillsides. If you happen to be driving at night, you notice the Christmas lights on the drilling rigs instead of the stars.

But what’s invisible even now is the full impact of the Powder River project, the damage that 70,000 wells and their infrastructure might do. For now you can see only patches of development, still unconnected, for the most part, by the roads and pipelines and power lines it will take to bring all of the planned wells into production. You still see a landscape that resonates in the American imagination and will resonate forever if it’s left alone. But if the methane play goes the way the players want it to go, they’ll take one year’s worth of methane out of the ground, turn it into cash and electricity, and watch it disappear at the hands of American consumers. But in the basin, nothing will ever be the same again.