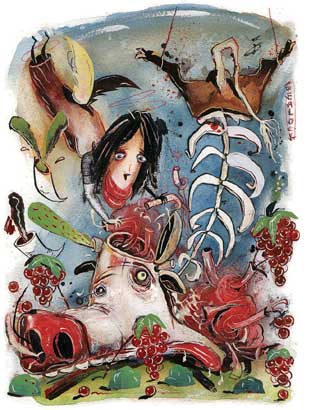

Illustration: Rick Sealock

the making of Preparation 503 began just after dawn on a cold October morning at Stephen Decater’s Live Power Community Farm. As the sun rose over Northern California’s bucolic Round Valley, Decater waited near the barn where an 18-month-old Angus cross named Red was chewing his last breakfast. Although he seemed relaxed, this was a solemn affair for the 59-year-old Decater, who’s spent the last 23 years running his family’s 40-acre farm under the principles of biodynamics, an alternative organic farming method that attaches near-religious significance to otherwise mundane activities such as planting, harvesting, and slaughter.

“Before I prepare to kill an animal from the farm, my attitude is one of gratitude for the animal’s life,” he told me. He said a silent prayer, moved quietly to Red’s stall, pointed a .22 rifle between the bovine’s chocolate-brown eyes, and fired a single shot that dropped nearly 1,000 pounds of animal to the ground.

Red’s sacrifice was part of a ritual repeated every autumn, when Decater harvests the raw materials to make homemade tinctures or, as they are called in biodynamic-speak, “preparations” or “preps.” After the cow is butchered, Decater and a handful of volunteers pull out its entrails and stuff them, sausagelike, with chamomile and other flowers, creating Preparation 503, which is added to the farm’s compost piles. They also tamp its manure into cow horns, which are buried. Come spring, the horns are unearthed, their rotted contents transformed into Preparation 500, believed to stimulate root formation. For every acre, five tablespoons are mixed with five gallons of water, then applied to the crops and the soil. Over the course of the growing season, other preps such as 501 (quartz in a horn) are sprayed on the plants and into the air around the farm; 505 (oak bark) and 506 (dandelion) are put in compost and then worked into the soil. It’s like homeopathic medicine: Small, almost imperceptible quantities of substances imbued with special forces are supposed to have a beneficial effect on the vitality of the soil and the crops.

To hear its adherents tell it, a biodynamic farm isn’t just a place to produce food; it is a convergence zone for cosmic forces that work on the plants, animals, soil, microbes, and—maybe most importantly—the farmer. This is what convinced Decater to convert from organic agriculture to biodynamic in the mid-1980s. “I was out pruning my trees, the fruit trees,” he recalled, “and I realized, ‘I have no idea what I’m doing.'” Not in a literal sense, but in a spiritual sense. Now he envisions his farm as a self-sufficient organism: Horses till the fields, sheep provide meat, chickens lay eggs, cows give milk—and all of them contribute manure, which feeds the plants, which feed the people, who care for the land. “Everything is serving something else,” he said. “Biodynamics is trying to talk about reverence for everything in the world. We want to bring beauty and light into the world.”

Taste the Magic

tasting wine is best done in natural light and with real wine glasses. We had neither, but that didn’t stop us from blind taste-testing California syrahs to see if we could swirl and sniff our way through the biodynamic hype. The verdict: You get what you pay for. Here’s our in-house oenophiles’ (and a few philistines’) rankings, from least drinkable to most:

Frey Vineyard Redwood Valley Syrah 2005

Biodynamic, $16

Comments: “Full flavor, but all over the map”; “Velvety, a bit of leather”;”Smells like Band-Aids and tastes like old tire.”

Pepperwood Grove California Syrah 2005

Conventional, $9

Comments: “Not brilliant but good”; “Too sweet”; “Tastes more of tin or some other metal than of grape. I wouldn’t make stew with this.”

Bonterra Vineyards Mendocino Syrah 2004

Organic, $16

Comments: “Bright berry flavor”; “Undistinctive”; “Smells like a barnyard, stings like a bee.”

Patianna Mendocino Syrah 2003

Biodynamic, $30

Comments: “Full, velvety, jammy”; “A touch of Manischewitz”; “Long flavor profile with rounded peaks, flowers in the finish, fruity, crisp mouth feel.”

Clos Saron Sierra Nevada Syrah 2003

Biodynamic (uncertified), $35

Comments: “Comes alive on the tongue”; “Very full. Yummy”; “Bright dramatic flavor that jumps out at you.” —N.C.

Biodynamic farming has been well known, if not mainstream, in Europe since the late 1920s, but perhaps due to its mystical bent it’s been slow to catch on in the United States. Yet that may be changing as more people see it as an alternative to Big Organic. After all, biodynamic adheres to strict rules that large commercial and corporate organic operations can’t hope to follow. As one agricultural theorist writes, biodynamic “makes typical organic farming look like strip mining.” Currently, there are only 102 biodynamic farms and 40 biodynamic wineries in the United States. But that number is steadily growing. Jim Fullmer, the executive director of Demeter usa, which issues its trademarked biodynamic seal to farmers who follow its guidelines, says he’s struggling to keep up with the demand from farmers to be certified.

i first heard about biodynamic at one of those Bay Area dinner parties where no one had ever been to a Wal-Mart, yet everyone was appalled that it was selling lettuce stamped with the usda Organic label. The alternative to the new organic-industrial complex, one woman offered, was biodynamic. She said the biodynamic food she’d eaten in France had been the tastiest she’d ever had; the lettuce had had a certain “force” to it. As the daughter of organic back-to-the-landers, I’m fascinated by alternative farming methods, though I like to temper my enthusiasm with a side order of skepticism. Which is how I came to spend several weekends working at the Live Power farm, breaking my back harvesting its melons, prodding its revered compost piles, witnessing the cosmos-capturing steer slaughter, and quietly wondering if this wasn’t all just a bunch of hocus-pocus.

Before my visit, I did a background check on biodynamic. All roads led to one elusive man: Rudolf Steiner. In America, the Austrian philosopher is most famous as the father of the holistic Waldorf education movement. In Europe, he’s also known as the father of biodynamic agriculture, which he introduced nearly 20 years before the organic movement took off. Steiner had little practical knowledge of farming, but that didn’t stop him from laying out detailed ideas for an agriculture that relied upon cosmic forces instead of chemical fertilizers. The theory behind biodynamic isn’t exactly easy to grasp; Steiner’s lectures feature cryptic statements such as, “At the moment when the seed is placed in the soil it is strongly worked upon by the terrestrial forces and it is filled with the longing to deny the cosmic forces, in order that it may spread and grow in all directions.” Steiner once admitted to an audience, “To our modern way of thinking, this all sounds quite insane. I am well aware of that.”

However, Steiner expected that science would eventually support his theories, and he may yet be proved right. When I mentioned biodynamics to Garrison Sposito, one of the world’s most well-regarded soil chemists, I was surprised that he agreed with its basic principles. What about sticking valerian root and dandelions into a compost pile? “Small amounts of certain things can make a difference,” said Sposito, who teaches at the University of California-Berkeley. “There might be microbes that are activated, or they might slow-release certain enzymes.”

In the early 1990s, John Reganold, a soil science professor at Washington State University’s Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, started comparing conventional and biodynamic farms. His research, published in Science, found that biodynamic farms had higher quality soil than conventional farms and were just as economically viable. Later studies found no difference between biodynamic and organic crops, and Reganold noted that no one really knows how the preps work. “I’m not an organic freak,” he told me, yet he called biodynamic “the most holistic system I’ve seen.”

But being biodynamic isn’t easy. Demeter usa has codified the world’s most stringent organic agricultural guidelines, delineated in a 25-page document that frowns upon artificial fertilizers, petroleum products, and other features of “unsustainable agriculture-related industry.” Which partly explains why the Decaters have no tractors, just four enormous Belgium draft horses. Antique farm implements are strewn about the farm. I thought the tools were touchstones of authenticity a la Martha Stewart until I watched sweat pour off an apprentice’s brow as he tilled a field, the horses straining to pull a steel plow through dark, weedy earth. Demeter also has a strict ban on “parallel production”—a farm must be entirely biodynamic or not at all. Monocrops are forbidden and 10 percent of a farm’s acreage must be set aside as a natural preserve.

Biodynamic’s small scale and anticorporate ethos mean that you won’t find it at Whole Foods or even at your local farmer’s market anytime soon. Live Power only distributes its harvest through a community-supported agriculture program in which customers “subscribe” to a year’s worth of produce.

Finding biodynamic wine is another story, however. Winemakers have always prided themselves on their terroir, the unique taste that a vineyard’s soil imparts on its grapes—a very Steinerian idea. And winemakers have never been afraid to embrace whatever it takes to set their products apart. French winemakers started going biodynamic in the 1990s; in 1997, the snooty, 300-year-old Domaine Leflaive vineyard made the switch after blind taste tests almost unanimously favored its wine made from biodynamically grown grapes. (Vineyards are exempt from the no-monoculture rule.)

Californian winemakers, still smarting from organic wine’s mediocre reputation, were initially slow to see biodynamic’s cachet. (See “Taste the Magic,” above.) But soil scientists such as Reganold are now courted by well-heeled wineries, and it’s not uncommon to see a reverential photo of a pile of cow horns in the wine section of a California newspaper. When a biodynamic viticulture consultant writes that “the grape is a truly cosmic plant,” wine drinkers don’t smirk; they reach for their checkbooks. A biodynamic Napa Valley Araujo Cabernet Sauvignon 2003 recently earned a 91 from Wine Spectator and sells for $215 a bottle.

after red was killed, a small crowd assembled as a traveling butcher skinned the carcass and winched it into the air. The entrails, the size of a small sofa, slid out in one giant blob and were laid out in the afternoon sunlight. Then the volunteers set out to harvest the rest of the prep-making materials. We walked around the pasture, heads bowed, looking for the holy in cow pies. Harald Hoven, a biodynamic farmer and instructor at California’s Rudolf Steiner College, paused to consider a fresh specimen. “Notice how it is perfectly round,” he said with a slight German accent, remarking on “how much life and vitality it has.”

Flies and yellow jackets buzzed a couple stuffing chamomile flowers into a soggy section of small intestine. Hoven deposited Red’s head near a hose, where two girls were on brain-removal detail. Normally, these sights would have sent me running, but the group was calm and purposeful. Its faith in the importance of what it was doing had a mesmerizing effect. “By collecting the manure and further contracting it into a cow’s horn, we’re sort of filing away the energy of the farm for the winter,” explained Marney Blair, who runs a biodynamic farm. She said she’s been called crazy for believing in things like Preparation 503. “Sometimes it feels like we’re floating way out there. But there’s a longing to connect in an extremely deep way. It’s gospel.”

As the day came to a close, the group filed over to a large pit that Decater and his three teenage sons had dug the day before. I gasped. I had already witnessed the death and dismantling of a large mammal and magic-potion making. But nothing prepared me for this: four feet of topsoil the color of a moist fudge brownie. Over the decades, millions of worms and billions of microbes had created this loamy home. Maybe they really do like yarrow, dandelion, chamomile, and cow poop. Hoven reached into the hole and began to stack the manure-laden horns, tips up. The chamomile-and-intestine sausages were to be taken to a place where snow would eventually cover them so, as Steiner had proclaimed, “the cosmic-astral influences will work down into the soil where the sausages are buried.”

The ritual was over, and so was the season. It was up to the subterranean creatures to finish the job. Before I took my leave, I remembered my initial visit to the farm. One morning, I had met Decater in a sweet-smelling herb field, where he patiently demonstrated the proper way to clip basil. As we picked, I noticed that his basil had a durability to it that the plants in my backyard garden lacked. The leaves and stems felt stronger.

When Decater carried away a full lug box, I snuck a leaf into my mouth. It certainly tasted better than my own crop. Somehow it seemed richer, with a complex tingle that stayed on my tongue. Or maybe I was imagining things.

Grape Britain?

the last time England had a reputation for its wine was more than 700 years ago, when British monks took advantage of the 400-year-long Medieval Warm Period to grow and press grapes. Today, a new round of climate change is putting the island’s wines back on the map.

Thanks to its newly hot, dry summers, the south of England is now considered wine country. Nearly 400 vineyards are producing $31 million worth of wine annually, and they’re drawing attention for their surprisingly good rosés, whites, and sparkling wines. England swept the sparkling wine category at the 2006 International Wine and Spirit Competition; the Nyetimber Classic Cuvée 1998 from West Sussex was named the world’s best sparkling wine outside of France’s Champagne region.

As the latitudinally challenged English wine biz heats up, climate studies predict that established grape-growing regions like France, Spain, and California will be struggling; Napa Valley could see its wine production drop up to 80 percent in this century. Meanwhile, formerly gauche newcomers such as Tasmania and Canada are being touted as the next “star regions.” Last year, British vintner Thomas Shaw released his vintage three weeks before Beaujolais Nouveau, a French wine that is traditionally the first of the season. “The temperatures made a huge difference,” Shaw told a British paper. “The fruit was coming off faster than had ever been known before.” —Jen Phillips