In the midst of debating a bailout package for Wall Street, the Senate took a break last night to vote on a measure that, although buried in the current news cycle, carries real consequence for the future of the world’s already troubled nuclear nonproliferation efforts: in a vote of 86-13, the Senate approved the Bush administration’s plan to begin supplying India with civilian nuclear reactors, nuclear fuel, and other related technologies. In return, India will open 14 civilian nuclear reactors to inspection by the International Atomic Energy Agency; 8 more military nuclear sites will remain off limits. The Senate vote followed House approval of the measure last week and a decision last month by the Nuclear Suppliers Group (a consortium of 45 nations involved in nuclear trade) to issue a waiver to India recognizing its status as a nuclear weapons state.

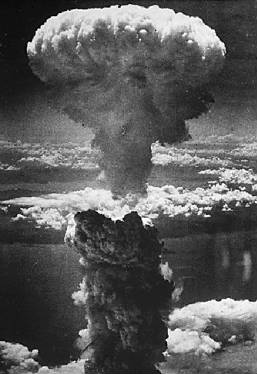

India has been a nuclear weapons pariah since it first exploded an atomic weapon in 1974. (The Nuclear Suppliers Group was established at U.S.-urging after the India test to prevent the country from obtaining additional nuclear capability; it was then aligned with Soviet Union.) Even today India has yet to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and additional nuclear tests in 1998 strengthened international opprobrium and led the Clinton administration to impose economic sanctions.

But all that is now history. Whereas the United States once viewed India through the prism of Cold War politics, it now sees the country as a crucial counterweight in its new power game with China. And the so-called U.S.-India Civil-Nuclear Agreement (known in trade circles as the “123 Agreement”) solidifies the new strategic partnership.

The bill passed Congress by comfortable margins in both houses and, given its implications for nonproliferation efforts, has some surprising proponents—among them Senator Richard Lugar (R-Ind.), a leading nonproliferation voice, who told the New York Times that “the national security and economic future of the United States will be enhanced by a strong and enduring partnership with India.” He was joined by John McCain, who released a statement this morning congratulating Congress on passing the agreement and suggesting it “allows [India] to become further integrated into the global effort to control proliferation of dangerous technologies,” and will enable the country to produce energy “without relying on greenhouse gas-emitting fossil fuels.” (India currently generates only 3 percent of its energy from nuclear power, due in part to the effectiveness of international efforts to restrict its nuclear trade.)

The latter point pales in comparison to what the deal could mean for nonproliferation. Despite claims by McCain and others (Democrats and Republicans) that the agreement will bring India under international safeguards and compel it to comply with inspections, what it really does, say critics, is create a country-specific exemption to nuclear proliferation controls and sets a poor example to other nuclear aspirants, like Iran, as to what can eventually be gained from recalcitrance. As Senator Byron Dorgan, Democrat of North Dakota, told the Times, “We have said to India with this agreement: ‘You can misuse American nuclear technology and secretly develop nuclear weapons.’ That’s what they did. ‘You can test these weapons.’ That’s what they did. And after testing, 10 years later, all will be forgiven.”

Aside from giving China something to think about, the deal is also about money. There’s a lot of it to be made in supplying India, the world’s second most populous country, with energy. And Washington isn’t the only one vying for the job. Just last night, the French government announced that it had inked a deal with India to provide at least two civilian nuclear reactors, to be built by Areva, a French power company. Russia is also interested in joining the bidding. India is in the market to grant up to $27 billion in contracts for 18-20 nuclear reactors, and estimates indicate that contracts could total $175 billion over the next 25 years—not nearly as much as it will take to bail out the U.S. economy, but still, big money. Among the U.S. companies lining up at the trough are General Electric, Westinghouse, and Bechtel.

The consequences of the U.S.-India nuclear deal will show themselves slowly, and perhaps in part for that reason, not much has been made of it in the press or in Congress. Immediately after casting their votes last night, Senators returned to debating the financial industry bailout package, the India deal just another piece of business checked off the list. For a measure so important to the future of the spread of nuclear weapons, said Dorgan, “never has something of such moment and such significance and so much importance been debated in such a short period of time and given such short shrift.”