Photo by flickr user <a href="http://www.zieak.com" target="new">Zleak</a> used under a Creative Commons license.

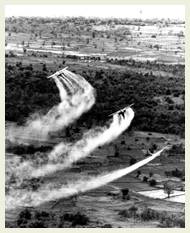

The Ford Foundation will release a report Tuesday calling for continued study of the environmental and health effects of Agent Orange, as well as for stepped-up diagnosis and treatment of US veterans exposed to it. Used as a defoliant in Vietnam to destroy vegetation used as food and cover for the Viet Cong, the dioixn--named for the orange stripe on its label–has been the subject of controversy ever since its first use in 1962. Over the ensuing ten years of hard combat, some 20 million gallons of Agent Orange and other toxic herbicides were sprayed over six million acres of Vietnamese jungle. (See the box below for a selection of Mother Jones‘ earlier coverage of Agent Orange and the federal government’s history of inadequate response to veterans’ complaints.)

Agent Orange’s widespread use in Vietnam was not the only instance in which US soldiers were exposed to harmful chemicals without a clear understanding of the risks; see my recent piece about a group of vets suing the federal government for their unwitting treatment as guineau pigs during US Army and CIA chemical weapons experiments at Edgewood. But in terms of scale, Agent Orange is without parallel. Hundreds of thousands of US troops and many millions of Vietnamese soldiers and civilians were exposed . The precise number of those placed in danger will never be known, nor will the number who have since died from health complications.

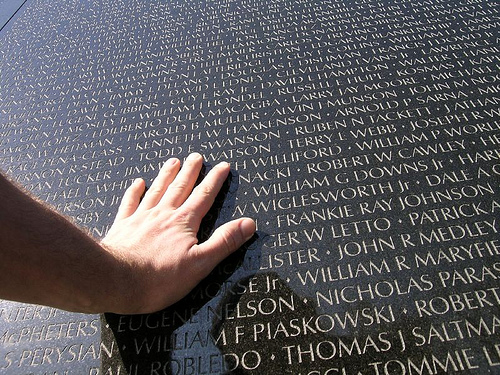

The aim of the Ford Foundation’s report is to take a look at what’s been done so far in terms of diagnosis and treatment of US vets (not as much as should have been) and to urge expanded care, not only for vets but for their children, many of whom now appear to be suffering next-generation effects from their parents’ toxic exposures.

From the report:

There is, in short, a presumed entitlement to care, services, and monetary assistance for America’s Agent Orange victims, but no overarching system for fulfilling that entitlement except the private knowledge, initiative, and perseverance of each individual veteran. More than 50 voluntary organizations–nearly all of them formed by veterans themselves–manage to reach and help many former service members. But these Veterans Service Organizations have many competing priorities and limited resources, and are responding to the consequences of more recent wars.

Meanwhile, the official list of diseases that are recognized as herbicide-related has grown only sporadically, in reponse to an underfunded and uneven process of epidemiological research adn bureaucratic deliberation. More than a decade after the war’s end, only one illness–the disfiguring skin disease chloracne–was offically recognized as connected to wartime Agent Orange exposure. Others have since been added, little by little, often after prolonged scientific and governmental debate. Many illnesses that Vietnam veterans suspect are associated with contaminated herbicides, such as brain or testicular cancer, still are not considered service-related and thus are not eligible for benefits…

At a minimum, men and women who risked their lives for the US war effort in Vietnam–and who in the process were exposed not only to enemy hostility but to poison from their own side–are entitled to a simple, consistent way of learning about and receiving the compensation and support to which the law already entitles them. But more broadly, the process by which eligible illnesses are recognized and addressed under this law should not be mired in technical disputes and plodding deliberation nearly 35 years after the war’s end. Research and data-gathering need to accelerate to a pace that begins to make up for decades of procedural delay and that fills in the gaps in basic information on exposure, medical consequences, and benefits delivered.