Janesville Assembly was one of General Motors' oldest plants, employing 4,000 people at its height, turning out classic Chevy and GMC vehicles. In December 2008, the last GM truck rolled off the line. Danny Wilcox Frazier

For a related photo essay by Danny Wilcox Frazier, click here.

DRIVING THROUGH JANESVILLE, WISCONSIN, IN A DOWNPOUR, looking past the wipers and through windows fogged up with cigarette smoke, Main Street appears to be melting away. The rain falls hard and makes a lonesome going-away sound like a river sucking downstream. And the old hotel, without a single light, tells you that the best days around here are gone. I always smoke when I go to funerals. I work in Detroit. And when I look out the windshield or into people’s eyes here, I see a little Detroit in the making.

A sleepy place of 60,483 souls—if the welcome sign on the east side of town is still to be believed—Janesville lies off Interstate 90 between the electric lights of Chicago and the sedate streets of Madison. It is one of those Middle-Western places that outsiders pay no mind. It is where the farm meets the factory, where the soil collides with the smokestack. Except the last GM truck rolled off the line December 23, 2008. Merry Christmas Janesville. Happy New Year.

The Janesville Assembly Plant was everything here, they say. It was a birthright. It was a job for life and it was that way for four generations. This was one of General Motors’ oldest factories—opened in 1919. This was one of its biggest—almost 5 million square feet. Nobody in town dared drive anything but a Chevy or a GMC.

Back then GM was the largest industrial corporation in the world, the largest carmaker, the very symbol of American power. Ike’s man at the Pentagon—a former GM exec himself—famously said, “What was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa.” Kennedy, Johnson, Obama, they all campaigned here. People here can tell you of their grandparents who came from places like Norway and Poland and Alabama to build tractors and even ammunition during the Big War. Then came the Impalas and the Camaros. In the end they were cranking out big machines like the Suburban and the Tahoe, those high-strung, gas-guzzling hounds of the American Good Times.

Today, some $50 billion in bailouts later, GM is on life support and there is a sinking feeling that the country is going down with it. Those grandchildren are considering moving to Texas or Tennessee or Vegas. Who is to blame? Detroit? Wall Street? Management? Labor? NAFTA? Does it matter? Come to Janesville and see what we’ve thrown away.

Today, some $50 billion in bailouts later, GM is on life support and there is a sinking feeling that the country is going down with it. Those grandchildren are considering moving to Texas or Tennessee or Vegas. Who is to blame? Detroit? Wall Street? Management? Labor? NAFTA? Does it matter? Come to Janesville and see what we’ve thrown away.

For years, the people here heard rumors that the plant was on its way out. But no one ever believed it, really. Something always came along to save it. Gas prices went down or cheap Chinese money floated in. Janesville was too big to ignore. Too big to close.

And then they closed it.

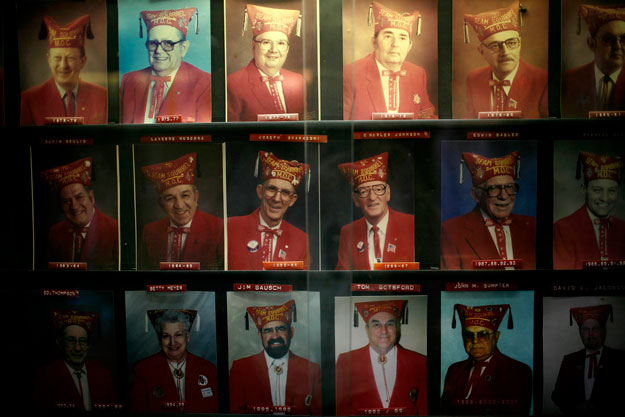

The local UAW union hall is quiet now. A photograph from a 1925 company picnic hangs there. The whole town is assembled near the factory, the women in petticoats, the children in patent leather, the men in woolen bowlers. The caption reads, “Were you there Charlie?”

Todd Brien’s name still hangs in the wall cabinet—Recording Secretary, it reads. But that is just a leftover like a coin in a cushion. Brien, 41, moved to Arlington, Texas, to take a temp job in a GM plant down there in April. He left his family up here. He is one of the lucky ones. Most of the other 2,700 still employed after rounds of downsizing had no factory to go to. But now, what with the bankruptcy of GM, he’s temporarily laid off from Texas, and back in Janesville to gather his family and head south.

“It was always in the back of my mind around here…They can take it away,” Brien says. “Well, they did. Now what? Can’t sell my house. Main Street’s boarding up. The kids around here are getting into drugs. You wonder when’s the last train leaving this station? I just never believed it was going to happen.” Today, freight trains leaving from Janesville’s loading docks take auctioned bits and pieces of the plant to faraway places: welding robots, milling machines, chop saws, drill presses, pipe threaders, drafting tables, salt and pepper shakers.

“It was always in the back of my mind around here…They can take it away,” Brien says. “Well, they did. Now what? Can’t sell my house. Main Street’s boarding up. The kids around here are getting into drugs. You wonder when’s the last train leaving this station? I just never believed it was going to happen.” Today, freight trains leaving from Janesville’s loading docks take auctioned bits and pieces of the plant to faraway places: welding robots, milling machines, chop saws, drill presses, pipe threaders, drafting tables, salt and pepper shakers.

Janesville is still a nice place. They still cut the grass along the riverbank. The churches are still full on Sunday. The farmers still get up before dawn. But there are the little telltale signs, the details, the darkening clouds.

This story was first published in Sept. 2009 with the headline “End of the Line.”

Janesville still looks like Heartland, USA—a giant fiberglass cow even marks the entrance into town. But restaurants are all but empty, and school enrollment is down.

Janesville still looks like Heartland, USA—a giant fiberglass cow even marks the entrance into town. But restaurants are all but empty, and school enrollment is down.

The strip club across the street from the plant is now an Alcoholics Anonymous joint. There are too many people in the welfare line who never would have imagined themselves there. Dim prospects and empty buildings. A motel where the neon “Vacancy” sign never seems to say “No Vacancy.”

The owner is Pragnesh Patel. He is 36, looks a dozen years older. He left a good job near Ahmedabad, India, as a supervisor in a television factory, he says. He came to try his luck in America. He got a job in a little factory in Janesville that makes electronic components for GM. He also bought the motel just up the hill from the assembly plant. Now with the plant closed, he’s down to three shifts a week at the components factory and having to make $2,500 monthly payments on his motel on Highway 51. He charges 45 bucks a night and today it’s mostly the crackheads and the down-at-their-heels who come in for a crash landing. Welcome to America, except Patel has to raise his children amid this decay. “I’m trying, really trying to survive,” he says. “I don’t know anymore. I mean, I’m an American. I cast my lot here. But I have to tell you, on many days, I regret that I ever came.”

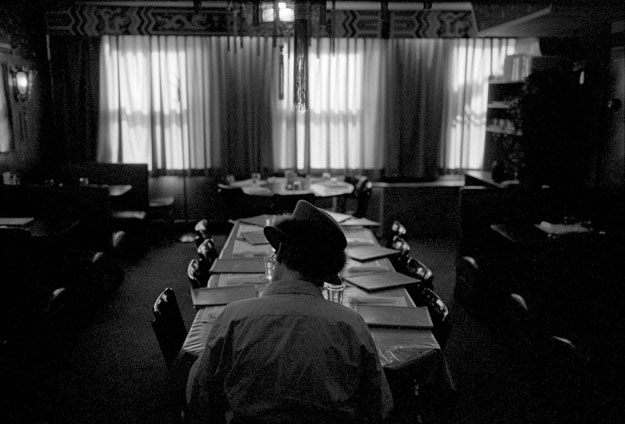

There is a bar on the factory grounds that has become a funeral parlor. Yes, a bar on the factory grounds, not 500 feet from the time clock! Genius! It has been here since at least the Depression if the yellowed receipt from 1937 is to be believed. Five cases of beer for 8 dollars and 30 cents.

And in some way, that bar on the factory grounds might explain what happened here. “We used to have a drive-through window,” says one of the former UAW workers gathered at Zoxx 411 Club and drinking a long, cool glass of liquor at three in the afternoon. He is about 50, about the age when a man begins to understand his own obsolescence. “Used to put two or three down and go back to work. Now those were the days, yes-siree.”

Janesville was a company town, where generations of GM workers met at the VFW to cap off a hard day’s work.You feel sorry for that autoworker until you hear he draws nearly three-quarters of his old salary for the first year of his layoff and half his salary for the second year of his layoff—plus benefits.

Janesville was a company town, where generations of GM workers met at the VFW to cap off a hard day’s work.You feel sorry for that autoworker until you hear he draws nearly three-quarters of his old salary for the first year of his layoff and half his salary for the second year of his layoff—plus benefits.

“It don’t make sense to work,” says the autoworker, buying one for the stranger.

If he finds a job, he says, they’ll take his big check away.

“There ain’t no job around here for $21 an hour,” the autoworker says. “I might as well drink.”

A taxpayer-funded wake. Good for him. Except you get the feeling that it’s not good for a man to drink all day. Two years comes faster than a man thinks.

A town of Cooties and 4-Hers is now also a town of moving trucks and permanent yard sales.A little Detroit in the making, except Detroit has General Motors and Ford and Chrysler. Detroit is an industry town. Janesville had only General Motors. Janesville was a company town. You didn’t have to go to college—but you might be able to send your kid there—because there was always GM. GM—Gimme Mine. GM—Grandma Moo, the golden cow. Now GM has Gone Missing. GM has Gone to Mexico.

A town of Cooties and 4-Hers is now also a town of moving trucks and permanent yard sales.A little Detroit in the making, except Detroit has General Motors and Ford and Chrysler. Detroit is an industry town. Janesville had only General Motors. Janesville was a company town. You didn’t have to go to college—but you might be able to send your kid there—because there was always GM. GM—Gimme Mine. GM—Grandma Moo, the golden cow. Now GM has Gone Missing. GM has Gone to Mexico.

“We took it for granted,” says Nancy Nienhuis, 76, a retired factory nurse who farms on the outskirts of town. She did everything at that plant a nurse could do: tended to amputations, heart attacks, shotgun wounds inflicted by a jilted lover, even performed an exorcism of spiders from a crazy man’s stomach. Whatever it took to keep those lines moving.

Unemployment in Janesville is now the highest in Wisconsin. The local food bank serves 10 percent more people than it did a year ago“The rumor would start, they’re talking about closing the plant. No one would believe it. Then you saw the Toyota dealership open on the east side of town and still they didn’t believe it. The manager and the worker sat next to each other in church, you see? They went to high school together. Understand? The good worker got no recognition over the bad worker. Nobody made waves about a guy drunk or out fishing on the clock. In the end, the last few years, management rode them pretty good. But by then it was a little too late.”

Unemployment in Janesville is now the highest in Wisconsin. The local food bank serves 10 percent more people than it did a year ago“The rumor would start, they’re talking about closing the plant. No one would believe it. Then you saw the Toyota dealership open on the east side of town and still they didn’t believe it. The manager and the worker sat next to each other in church, you see? They went to high school together. Understand? The good worker got no recognition over the bad worker. Nobody made waves about a guy drunk or out fishing on the clock. In the end, the last few years, management rode them pretty good. But by then it was a little too late.”

Most laid-off GM assembly workers are paid severance for two years. “There’s going to be hell to pay when those unemployment checks stop coming,” says one resident.

Most laid-off GM assembly workers are paid severance for two years. “There’s going to be hell to pay when those unemployment checks stop coming,” says one resident.

Richard, a former welder at the plant, puts a pastry box in Nurse Nancy’s car. Richard begins to weep. He looks over his shoulder, wipes his nose on his sleeve and says, “I don’t want my wife to see this. I’m 62 and I’m delivering doughnuts. What am I going to do?'”

Desperation comes in subtler ways than a grown man crying. The winner of the cakewalk at the local fair got not a cake—but a single, solitary cupcake. Parents don’t come to the PTA as much anymore. A lot of kids will have left by the beginning of the school year, the superintendent says. Unemployment here is near 15 percent. The police blotter is a mix of Mayberry and Big City: Truancy, Truancy, Shots Fired at 2 p.m., Dog Barking, Burglary at 5 p.m., Burglary at 6 p.m.

At 7 p.m. they fry fish at the VFW hall. Beers 2 bucks. Two-piece plate of cod $6.95. Charlie Larson runs the place. You can see the factory from Charlie’s parking lot, the Rock River running lazily beside it. Charlie tried the factory in 1966. His father got him in, but he was drafted into the jungles of Nam in 1967. “It’s a discouraging thing,” Charlie, 61, says of the plant closing down, smoothing a plastic tablecloth. “It was the lifeblood of this town. It was the identity of this town. Now we have nothing, nothing but worry. Aw, there’s going to be hell to pay when those unemployment checks stop coming.”

Blame the factory worker if you must. Blame the union man who asked too much and waited too long to give some back. Blame the guy for drinking at lunch or cutting out early. But factory work is a 9-to-5 sort of dying. The monotony, the accidents. “You’re a machine,” says Marv Wopat. He put bumpers on trucks. A six-foot man stooping in a four-foot hole, lining up a four-foot bumper. Three bolts, three washers, three nuts. One every minute over an eight-hour shift. Wopat, 62, has bad shoulders, bad knees, bad memories. “You got nightmares,” he says. “You missed a vehicle or you couldn’t get the bolt on. You just went home thinking nothing except the work tomorrow and your whole life spent down in that hole. And you thinking how you’re going to get out. Well, now it’s gone and alls we’re thinking about is wanting to have it back.”

And maybe they will have it back. The recession is loosening its grip, some say. Some towns will rebound. Some plants will retrofit. Wind, solar, electric—that’s the future, Washington says. But you get a pain-in-the-throat feeling that it is not the future. Not really. At least not as good a future as the past. There’s no 28 bucks an hour for life in that future. No two-car garage. No bennies. No boat on Lake Michigan. Because in the new world they can build that windmill, or a solar panel, or an electric battery in India, where the minimum pay is less than $3 a day. Just ask Patel, the motel owner living at the edge of a dead factory in Janesville, Wisconsin. “You cannot compete with poverty unless you are poor.”

Charlie LeDuff is a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, filmmaker, and multimedia reporter. He was formerly a reporter for The Detroit News.

Motel owner Pragnesh Patel says he wishes he’d never come from India.

Motel owner Pragnesh Patel says he wishes he’d never come from India.