During his first confirmation hearing, Scott O’Malia got off easy. The nominee to the nation’s commodities watchdog agency was never asked about his role, years earlier, as a top lobbyist for a firm accused of Enron-style abuses, including manipulating California’s energy market and contributing to a statewide electricity crisis. That is, the very same type of market misconduct that the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) is charged with policing, if not preventing.

O’Malia, a Senate staffer who spent nearly a decade working for Mitch McConnell, was originally selected to serve as a CFTC commissioner by George W. Bush. But, after clearing the Senate agriculture committee, his nomination stalled. President Obama recently nominated him again, and O’Malia will soon face another confirmation hearing. This time around, though, he may face some tough questions about his two-year stint as the director of federal legislative affairs for Atlanta-based Mirant. Following a story by Mother Jones on his lobbying past, a spokeswoman for new agriculture committee chair Sen. Blanche Lincoln (D-Ark.) says O’Malia will be questioned about his history working for a company that pushed for deregulation and was the subject of a litany of lawsuits alleging unscrupulous business practices. “The confirmation process exists to fully vet nominees,” Katie Laning Niebaum, Lincoln’s communications director, told me. “Chairman Lincoln will address this matter in the hearing and looks forward to complete, transparent answers from Mr. O’Malia and all nominees.” (The hearing, which will include testimony from two other CFTC nominees, has yet to be scheduled.)

O’Malia’s nomination comes as the Obama administration is laying out a sweeping financial reform agenda—or, as the president himself put it last week, “the most ambitious overhaul of the financial regulatory system since the Great Depression.” In the past, the CFTC has often been seen as a feckless regulator, and strengthening its oversight of the futures and derivatives markets features prominently in the Obama administration’s agenda. That’s why some consumer advocates question why an ex-lobbyist for a company that gamed energy markets—Mirant eventually settled a spate of California lawsuits to the tune of a half billion dollars—has been chosen to fill this important seat. “This does not send a signal that wrongdoers are going to be held accountable,” say Tyson Slocum, the director of Public Citizen’s Energy Program and a member of the CFTC’s Energy and Environmental Markets Advisory Committee.

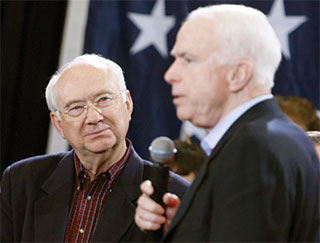

A White House official explained that Obama’s nomination of O’Malia had to do with protocol more than anything else. When a Democrat is in the White House, the top Senate Republican—in this instance, O’Malia’s former boss, McConnell—traditionally selects candidates for certain seats on independent government agencies. It’s “the sort of precedent we defer to,” the official said. But to CFTC observers like Slocum and Michael Greenberger, who directed the commission’s division of trading and markets in the late 1990s, this explanation doesn’t wash. Both said the president could easily request another candidate—one with a less controversial past and at least some commitment to the type of reforms the administration has in mind. “If the top Senate Republican nominated Charles Manson, is the president blindly going to nominate him?” asks Slocum. “Absolutely not. The president can say, ‘No, I’m sorry, with all due respect your nominee is unacceptable; please submit another one.'”

Meanwhile, some Democrats who have advocated strongly in the past to bolster the CFTC, arguing that it wasn’t doing enough to crack down on speculative trading and market manipulation, are holding their fire on O’Malia.

In the summer of 2008, after receiving the blessing of the agriculture commission, all that stood in the way of O’Malia and a seat on the commission was Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.). Before his nomination could come to a vote, she put a hold on it (and those of two CFTC commissioners who’d been renominated by President Bush) as a form of protest. She said the commission had failed to wield its “authority to police the oil and gas markets from possible manipulation” and refused to allow the nominees to move forward until the CFTC made progress on that front. Since then, she has continued to push for the commission to step up its enforcement. Last week she introduced legislation to give the CFTC more power to crack down on market manipulation. Remarking on the bill, she invoked Enron: “When bad-actors like Enron…manipulate commodities prices, Americans end up footing the bill, paying more for commodities like oil, gasoline, heating oil, food, and natural gas.” Indeed, such was the case with Mirant, one of Enron’s trading partners. But Cantwell’s spokeswoman says the senator has no plans to block O’Malia’s nomination. “She does not currently have any concerns with Mr. O’Malia being on the commission.”

Slocum, however, finds O’Malia’s nomination troubling. “It is definitely a serious problem that a former lobbyist for a company that had to pay a settlement to resolve allegations of criminal misconduct…is now being nominated to be a regulator,” he says. “The Obama administration should have done more due diligence. What they didn’t do, now it’s the job of the Senate.”