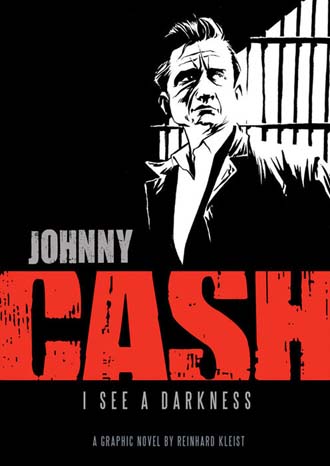

Reinhard Kleist’s brand-new graphic novel, Johnny Cash: I See a Darkness (Abrams Books), opens with a vintage Caddy (license plate “HELL”) barreling past a neon sign on the outskirts of Reno. Without a word, its surly driver—the Man in Black himself—makes his way to the strip, where he spots a short, wealthy, sleazy-looking man walking into an alley with a prostitute and proceeds to fill him with lead. In the scene’s final panel, the killer is inside an armored bus, pulling up to the gates of Folsom Prison. Get it? I shot a man in Reno / Just to watch him die.

The Berlin-based artist has fun with this concept in his well-researched biography of the late country star, segueing into pen-and-ink depictions of Cash hits like “Big River,” “Cocaine Blues,” and “A Boy Named Sue” (which unbeknownst to me was penned by Shel Silverstein). Kleist uses a different, faux-tribal drawing style for “The Ballad of Ira Hayes”—a choice that reflects his interest in Cash’s views on soldiers and war, an interest that also emerges in a studio scene with Bob Dylan.

If you caught the 2005 Cash biopic Walk the Line, with Joaquin Phoenix (the wrong actor as far as I’m concerned), you’ll recognize the basic outline: The Depression-era upbringing amid cotton fields in Arkansas, where a neighbor kid teaches young J.R. Cash to play guitar. The horrible mishap that befalls his brother Jack. The Air Force service in Germany. The courtship and marriage to Vivian Liberto. The settling down in Memphis and forming a band. The record deal, tours with Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis, leading to a devastating addiction to uppers. The public disgraces. And, of course, the forbidden love with June Carter, whom he eventually marries.

But Kleist creates a fresh narrative, too, with side stories and small details you won’t find in the film. Notably, he follows the character of Glen Sherley, a Folsom inmate who monitors Cash’s career closely from behind bars and writes a song that Cash ends up using when he performs at Folsom in his big 1968 post-rehab comeback. In the book, as in the film, the Folsom sessions stand out as the dramatic peak. But there the movie ends. Kleist fast-forwards a quarter century, to 1994 and a solo recording session with rap producer Rick Rubin at Cash’s cabin. By this time, Cash is an Old Man in Black, and through his chatter with Rubin we learn what became of Sherley after Cash helped get him sprung.

Artistically speaking, Kleist is a master of the genre who has spent much time studying Cash in all his facets—see his sketch gallery at the book’s conclusion. He experiments with composition enough that the eye is never bored, and in just two pages of silent pictures, he manages to express the agony of drug withdrawal as viscerally as any words could. Kleist does his homework, taking seriously his duties not simply as a graphic artist but as the biographer catering to a newer generation of fans, those first drawn in by Cash’s covers of artists like Danzig, Beck, and Soundgarden on Rubin’s American Recordings and its sequel, Unchained. Like Rubin, and the late Cash himself, Kleist found a way to push an old story in a new direction.

Click here for more Music Monday features from Mother Jones.