Photo courtesy Greenpeace Finland, <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/greenpeacefinland/4172062334/">via Flickr</a>.

In the final 48 hours of the Copenhagen climate conference, one of the biggest differences remains a very small number: half a degree.

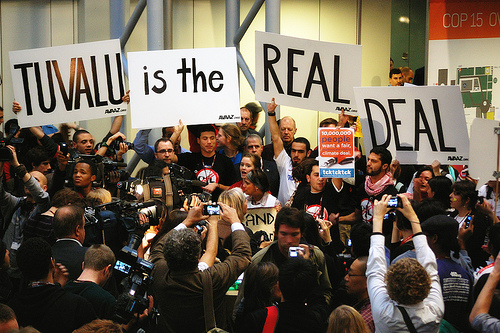

While most of the attention here is focused on the remaining divide between the United States and China when it comes to measuring and verifying emissions reductions, a much larger split remains between the 102 countries that have called for a limit on temperature rise of 1.5 degrees Celsius and the much more powerful nations that have called for a 2 degree target.

The nations pushing for a 1.5 degree target include members of the Alliance of Small Island States, the G77, the bloc of Least Developed Countries, the Africa Group, and several nations from Latin America and Asia. But there is significant pressure being exerted on these nations to consent to the 2 degree target that has been embraced the United States, European Union, China, and other nations here seen as the most powerful players in a final deal. But leaders from the 1.5 camp say they are holding firm on their target, and won’t sign onto a deal that calls for anything else.

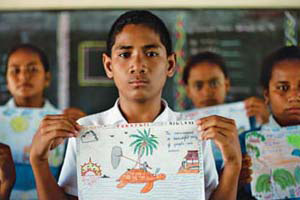

“I will not sign anything less than 1.5,” said Apisai Ielemia, Prime Minister of the tiny island nation of Tuvalu, which may become one of the first casualties of global warming. The low-lying Pacific island nation made headlines last week for shutting down talks with calls for a legally binding treaty. Now they’re staking out their desire for a deal at this summit that will not condemn them to rising tides, they say. “This meeting is about our future existence,” said Ielemia. “We don’t want to disappear from this earth … We want to exist as a nation, because we have a fundamental right to live beside you.”

“For developed countries to choose to not use that figure, is morally, politically irresponsible,” said Lumumba Stanislaus Di-Aping, the Sudanese chairman of the G77.

The debate over what figure to put in the final agreement here maybe meaningless, however, if the corresponding emissions reductions goals would not put the world on a path to stay below that limit. A leaked draft analysis from the UNFCCC of the commitments put on the table from developed countries states that what they have pledged so far would lead to a 3 degree temperature rise. If targets aren’t raised, “global emissions will remain on an unsustainable pathway,” the document states.

Meanwhile, frustrations remain high among developing nations over what they see as pressure from rich nations to consent to a higher target. “We are not yielding to these pressures, because our future is not negotiable,” said Ielemia.

He said that Australia and other unspecified developed nations have sought to meet with Tuvalu and representatives of other small island nations to urge them to accept the 2 degree limit, and promised that funding will be on the table for adaptation in return. Ielemia said Tuvalu declined the invitation. He was critical of the “backroom deals” that have been made here. “This is not how the United Nations should work,” said Ielemia. “We will leave this meeting with a bitter taste in our mouth, as the true victims of climate change have not been heard properly.”

But Dessima Williams of Grenada, chair of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), said she has seen positive efforts on the part of developed countries to hear their concerns. She noted that Prime Minister of Grenada Tillman Thomas spoke to Obama last night, and AOSIS members have also met in the past day with Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao, United Kingdom Prime Minister Gordon Brown, and US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. “Some of our leaders are having behind the scenes negotiations just like everybody else,” said Williams.

She also indicated that, while they are holding at this target temperature rise, there is hope that they will be able to craft language in a deal tomorrow that reflects their interests in some way. “We believe they are sympathetic to us,” she said. “We don’t know how it will come out in the wash, with the actual numbers, but as one of the many negotiations in the developing world I can tell you we have had big disagreements but very good will.”

The issue of climate aid money for nations like Grenada and Tuvalu remained another outstanding issue on Thursday, as groups were divided over whether the $100 billion fund by 2020 that Clinton endorsed that morning was sufficient. Tuvalu’s leader was critical, calling it an attempt to “hang a carrot in front of the eyes of the most vulnerable countries.” G77 chair Di-Aping was also dubious. While he said it was a “welcome signal” that the US was at least agreeing to a total fund, “we know pretty well that we need at least $400 billion.”

While it seems clear that a final agreement here won’t be as ambitious as developing nations have argued for, Williams said she remains hopeful about the process in the longer term. “Whatever is left on the table, it doesn’t go away,” said Williams. “We will be back to fight another day.”