Update: On March 1, 2010, a federal judge issued a decision ordering New York State to create 4,500 units of supportive housing for people currently living in adult homes. You can read more about the decision and its impact here.

NOT TOO MANY VISITORS to Coney Island wander down the boardwalk past the Cyclone, the Wonder Wheel, and Nathan’s Famous hot dogs, all the way to the shabby brick building at 2316 Surf Avenue. A century ago, this area was popular with vacationers; today this building, one block from the boardwalk, houses a very different population. Its name—Surf Manor, spelled out in red letters across the front—suggests grandeur, but there is nothing grand about this place. Out front, a few of the building’s residents huddle against the ocean wind, enveloped by the stench of cigars. Their choice of smoke testifies to their meager means: Nobody can afford cigarettes, which sell for at least $9 a pack at the bodega next door; Omega Little Cigars are just $3.50.

These men and women exist in a strange form of limbo. When New York state began downsizing its psychiatric hospitals in the 1960s, they were promised a chance to live in the community—but instead wound up relegated to the fringes of the city, warehoused in adult homes like Surf Manor. These privately owned, for-profit residences were originally set up to house the elderly, but soon they became New York’s de facto mental institutions: Today, in New York City alone, they house some 4,300 people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other serious psychiatric illnesses. Year after year, conditions inside these adult homes quietly deteriorated; not too many New Yorkers even knew what “adult homes” were, much less what went on inside them.

All this changed in 2002, when the New York Times‘ Clifford J. Levy wrote a Pulitzer-winning exposé detailing the worst sorts of abuses: residents preying on one another, including one who stabbed his roommate to death; workers shuttling residents to Medicare and Medicaid mills, where doctors performed unnecessary surgeries, then billed the government; residents literally roasting to death in their rooms for lack of air conditioning. It was the sort of bad press that can be amazingly productive—creating so much public scrutiny that state legislators have no choice but to fix a system everyone knows is broken. As the state health commissioner then told the Times, “The world of adult homes is going to change dramatically.”

Her promise never came to pass, though. One home did shut down and one doctor ended up in federal prison, but the day-to-day lives of adult-home residents remained unchanged. Frustrated by the lack of large-scale reform, a group of attorneys led by Disability Advocates Inc. took their case to federal court. In 2003, they filed a lawsuit accusing New York state of violating the Americans with Disabilities Act by keeping mentally ill people segregated in adult homes. In the summer of 2006, as the suit was wending its way through the courts, photographer Erica McDonald happened upon Surf Manor while visiting Coney Island. Over the next 18 months, she returned again and again, befriending residents, taking their portraits, distributing photos to her subjects, and shooting some more.

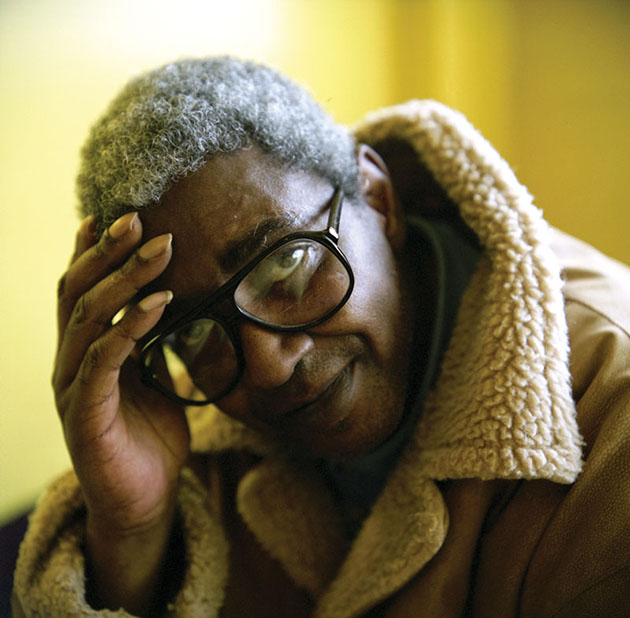

One Saturday, she invited me to join her on a visit. The scene in the lobby suggested a permanent state of inertia. Dozens of people sat slumped in a psychotropic daze, staring blankly at a TV. The building has some 200 residents, but the sign-in sheet at the front desk revealed they’d had only 13 visitors over the prior 14 days. A monthly schedule taped to the wall was packed with activities like bingo and blackjack, but as one longtime resident said, “If you believe the schedule, I’ve got a bridge I can sell you.” The high point of the afternoon came when residents lined up to wait for an aide to hand them their pills in a plastic cup. And then they went back to watching TV. Or staring at the walls. Or smoking outside.

Many of the residents arrived at Surf Manor straight from the psych ward of a local hospital—not because anyone decided Surf Manor was the perfect fit for them, but because they had nowhere else to go. “They told me if I don’t take Surf Manor, they were going to put me in the state hospital in Staten Island,” says George McGuire, a 55-year-old with a diagnosis of schizophrenia who previously lived in a homeless shelter. “I wasn’t given many choices.” Eddie DiJols, 55, says he used to sleep on the subway and the Staten Island Ferry before arriving here.

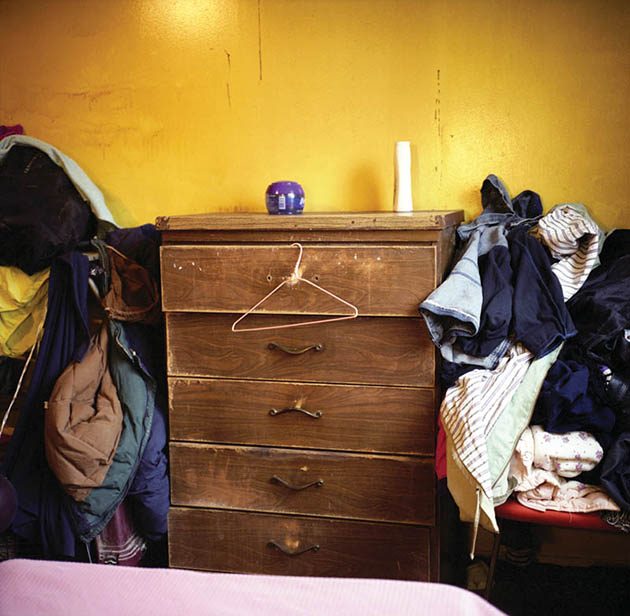

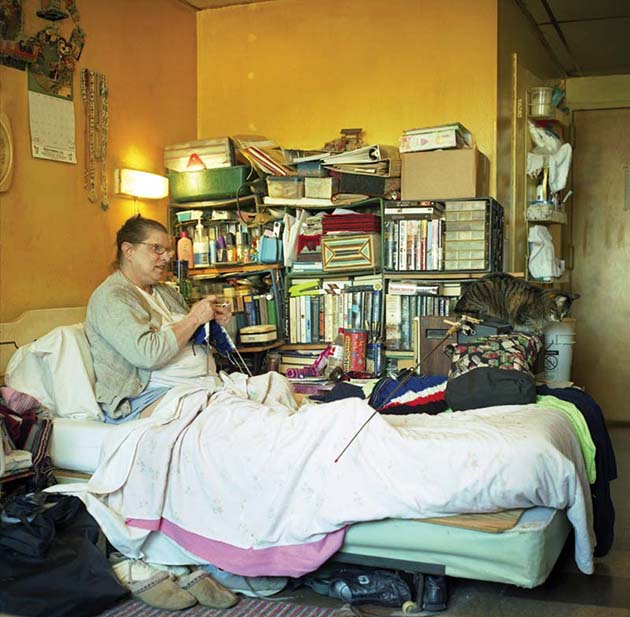

One of the residents’ chief complaints is that they are all treated the same, regardless of their capabilities. They have no access to a kitchen or washing machine, no control over what they’re served for dinner or when they get their monthly allowance. “You get stifled—and you regress. You become dependent on these people, and I don’t want that,” says DiJols, who used to work as a cook at hotels in the Catskills until, he says, “I had a breakdown.” Irene Kaplan has spent much of the last 16 years in bed here, reading or doing needlepoint or watching TV. “What I have to do for myself is almost nothing,” she says. “If you have any sense of individuality, if you’re at all independent—if you spend any time in an adult home, you’re going to start doubting yourself.”

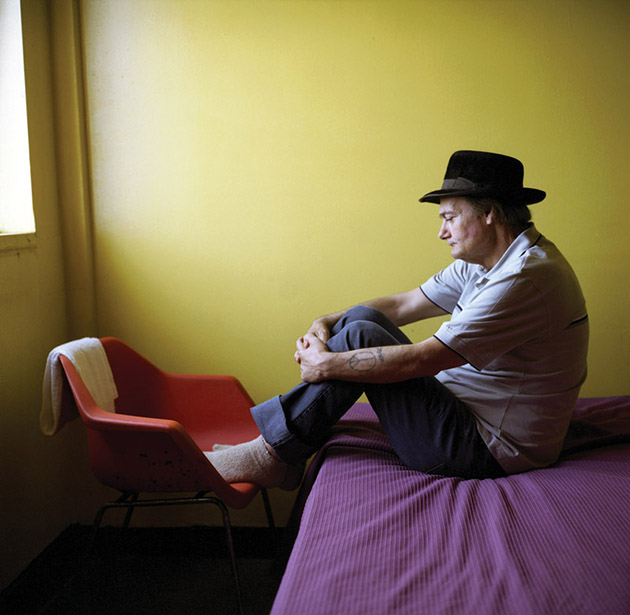

For advice, residents rely on one another, which usually means knocking on room 430. It’s the home of Norman Bloomfield, president of Surf Manor’s residents’ council, who came here straight from the psych unit of a local hospital. “I had no idea what an adult home was before I moved into one,” he says. Seven years later, he’s an expert. A onetime NYU student, now 62, he walks around with a Moleskine notebook in his pocket, recording his observations—and fellow residents’ complaints. What do residents dislike about Surf Manor? “The boredom. The sense that you’re not in charge of your own life. The lack of independence. The lack of a future.”

Bloomfield says, “For the first few months, my only thought was getting out.” But getting out is not so easy. Many residents are on Supplemental Security Income; after rent and board are deducted, they are left with just $198 a month. With so little income, they cannot afford an apartment of their own. Many dream instead of obtaining “supported housing”—an apartment with subsidized rent, where they could be in charge of their own cooking and pills and laundry, and which comes with a caseworker who visits regularly—but such apartments are virtually impossible to come by. Units are scarce; the process of applying is so bureaucratic it can confuse even the most capable individual; and adult homes have little incentive to help residents leave since fewer residents means less revenue. “They want all the beds filled up to get the maximum rent,” Bloomfield says.

In the eight years since the Times series appeared, New York City has added only 60 apartments for mentally disabled adult-home residents. That equation may be about to change, however, thanks to the lawsuit filed by Disability Advocates and several other nonprofits. All it took was six years, more than a dozen attorneys, and tens of thousands of hours of work, culminating in an 18-day trial in federal court featuring 30 witnesses and 300-plus exhibits. One expert witness for the plaintiffs described adult homes as possessing “some of the elements of a homeless shelter and some of the elements of a state hospital”; another characterized them as “little ghettos.” In September 2009, the judge ruled that New York state had indeed discriminated by isolating mentally ill people in adult homes. Among the exhibits presented to buttress the residents’ case were a few of Erica McDonald’s photographs from Surf Manor.

New York could appeal, but even if it doesn’t, it will likely take a few years before this courtroom victory translates into enough supported housing. In the meantime, the television in the lobby at Surf Manor stays on, the days drag by, and residents dream of a life no longer confined to an adult home on the edge of town, but in an apartment they can call their own.

The photographer thanks the Coalition of Institutionalized Aged and Disabled for assisting with this project.