Front page photo: <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/aheram/2535900393/">Flickr user Jayel Aheram</a>

It was just a single contract for a single job on a single base in Iraq. The Department of Defense agreed to pay the megacontractor KBR $5 million a year to repair tactical vehicles, from Humvees to big rigs, at Joint Base Balad, a large airfield and supply center north of Baghdad. Yet according to a new Pentagon report [PDF], what the military got was as many as 144 civilian mechanics, each doing as little as 43 minutes of work a month, with virtually no oversight. The report, issued March 3 by the DOD’s inspector general, found that between late 2008 and mid-2009, KBR performed less than 7 percent of the work it was expected to do, but still got paid in full.

The $4.6 million blown on this particular contract is a relatively small loss considering that in 2009 alone, the government had a blanket deal worth $5 billion with KBR (formerly known as the Halliburton subsidiary Kellogg Brown & Root). Just days before the Pentagon released the Balad report, KBR announced it had won a new $2.3 billion-plus, five-year Iraq contract. But the inspector general’s modest investigation offers new insight into just how little KBR delivers and how toothless the Pentagon is to prevent contractor waste. Moreover, the government’s own auditors predict that as the military draws down its forces in Iraq, KBR will keep most of its workforce intact, enabling it to collect $190 million or more in unnecessary expenses. Much of any “peace dividend” from the war’s gradual end—potentially hundreds of billions of dollars—could wind up in the hands of contractors.

On March 29, the bipartisan Commission on Wartime Contracting—which Congress set up in early 2007 to investigate waste and corruption in the military private sector—will hold a hearing to examine whether contractors are doing their part to prepare for leaving Iraq. Some commissioners are raring for a showdown with KBR over its drawdown plan—or lack thereof. The commission’s co-chair, former Republican congressman Christopher H. Shays, said in a statement: “Considering that KBR was just awarded a task order—now under protest—that could bring them up to $2.3 billion in new [Iraq-related] revenues, it’s very important that we get a clear picture of the quality of planning and oversight during the Iraq drawdown.”

The Balad report is likely to be a hot potato at the hearing. Commissioner Charles Tiefer tells Mother Jones the report is a “dynamite critique” of the firm’s practices. “The numbers translate into an astonishingly large pool of KBR employees standing around idle and having the government be charged,” he says.

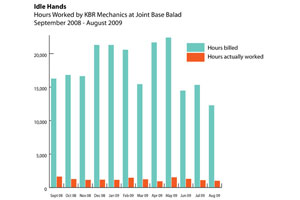

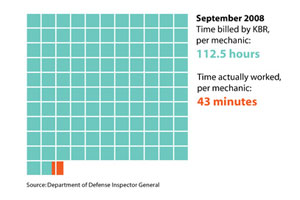

What the DOD investigators found in Balad was astounding. Army rules require that its civilian maintenance employees are actively working 85 to 90 percent of the time they are on the clock. Yet KBR’s own records showed that its workers were only engaged in labor an average of 6.6 percent of the time they were on duty. The DOD ran its own numbers, and its findings were even worse. In September 2008, for example, KBR had 144 maintenance employees at Balad, available to work 16,200 hours. Their actual “utilization rate” was a paltry 0.63 percent—which means that each of the 144 KBR employees averaged about 43 minutes of work for the entire month.

How did such a large bunch of thumb-twiddling mechanics go unnoticed? The Pentagon investigators found that the Army had no system in place to police how much work its contractors were actually doing. Plus, the unit in charge of KBR’s operation at Balad reported that the contractor wouldn’t reveal how many mechanics it employed there “because it believed the information was proprietary.” The investigators (who eventually got the KBR data) note that as of last August, the number of KBR mechanics at Balad has since dropped to 75, but they conclude diplomatically that “opportunities for additional reductions of tactical vehicle field maintenance services at [Balad] may exist, which may provide additional cost savings to DOD.” In other words, the Army should consider sending even more contractors home.

Some in the military appear to accept such waste as a matter of course. Col. Gust Pagonis, an assistant chief of staff for the 13th Expeditionary Sustainment Command, which took over command of Balad last August, responded to the DOD inspector general by explaining that “the contracting of maintenance capabilities, though not efficient, was effective in ensuring units did not experience low readiness rates and being able to perform the mission.” Translation: The KBR contractors were essentially being kept around on reserve, just in case. Tiefer doesn’t buy that argument. “That might justify a limited overcapacity, but nothing approaching KBR’s levels,” he says.

As the military draws down its own numbers in Iraq, that “just in case” fleet shows few signs of going home. By this August, all US combat personnel are slated to be out of Iraq, leaving a force of about 50,000 “combat support” troops. Yet if the DOD’s own optimistic estimates are accurate, there will still be 75,000 contractors in Iraq at the end of summer—or 1.5 contractors for every soldier. KBR had 17,095 employees in Iraq as of last September, but when its subcontractors are included, it oversees as many as 58,000 workers. The firm has promised to reduce its staff in Iraq by 5 percent each quarter, but that may not be fast enough. Last November, April G. Stephenson, the then-head of the Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA), testified to the contracting commission that KBR could cost the government another $193 million in unnecessary manpower between then and the August 2010 withdrawal date for combat forces. “When the military reduced its troop levels from 160,000 to 130,000—a 19 percent reduction—KBR’s staffing levels remained constant,” she told the commission, adding that KBR had so far refused to share “a detailed, written plan to reduce staffing levels in consonance with the military drawdown.”

She added that the $193 million estimate was “conservative”; if KBR fails to meet its withdrawal goals, the price tag could balloon by hundreds of millions more. “The drawdown in Iraq and these Iraq task orders are going to become a deep pocket for these contractors,” she told the panel. In light of the Balad report, Tiefer cautiously agrees. “If KBR has underutilized rates in many of its operations anywhere near the rates found by the inspector general study…that would support a search for savings on the order of $300 million,” he says.

KBR rejects those assertions. The company has “been working since last year with these organizations in responsibly planning our support to the drawdown of military forces in Iraq,” writes company spokeswoman Heather Browne in an email to Mother Jones.

Federal bean counters are concerned with more than just KBR’s inflated contracts. In fiscal 2009 alone, the DCAA identified $20.4 billion in questionable billing, and another $12.1 billion in unsupported cost estimates, by contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan. Together, that’s more money than any individual handout to the biggest beneficiaries of the financial bailout.

In October, the Pentagon transferred Stephenson to its payroll department. That move came after the Government Accountability Office complained about auditing irregularities on Stephenson’s watch. GAO even alleged that some DCAA reports had been modified to favor contractors—which suggests that the companies’ waste in Iraq and Afghanistan may be even worse than already known. (Stephenson could not be reached for comment.) But even before her demotion, Stephenson’s agency had little leverage with contractors. All the DCAA can do is make recommendations to an alphabet soup of other Pentagon bureaucracies that routinely insist that contracts and regulations prevent them from playing hardball with contractors and their paychecks. At the November hearing, Shays, the co-chair of the contracting commission, chastised a Defense Contract Management Agency representative for failing to withhold any payments to contractors—even after the DCAA had expressed doubts about the amounts the contractors were charging. “It is simply outrageous that DCMA did not respond to DCAA’s findings and have any withholds,” Shays said. “And it was unfortunate that DCAA did not have a way to see that resolved.”

The DOD’s inertia on contractor accountability is so complete that its agencies can’t say with any certainty how many contractors are currently in Iraq and Afghanistan. One April 2009 estimate put the number at 160,000; a separate DOD study a month earlier said it was 240,000. The dysfunction has angered some Iraq War hawks, like Shays and contracting commission member Dov Zakheim—a Bush-era undersecretary of defense who helped manage the war’s initial finances. Zakheim upbraided several Pentagon officials in that November hearing for not keeping contractors accountable. “We’ve been at war for eight years in Afghanistan, long enough for me to actually start forgetting about what it was like at the beginning, when I was there,” he said. “Eight years in Afghanistan, and we haven’t resolved something like this, which I would have thought is absolutely critical.”

But KBR will be in the hot seat at next week’s hearing—and on the heels of the Balad report, that seat’s now likely to be a lot hotter. “We’re hoping to find out at this hearing how much progress KBR has made toward a viable drawdown plan with realistic assumptions,” Tiefer says, adding: “I’m personally hoping to receive suggestions for how to reform monopoly cost-plus contracts like KBR’s.” Company spokeswoman Browne says KBR is ready to state its case, and is in the process of drafting a response to the inspector general’s report.

For now, however, it’s hard to see what the commission or the federal government can do to derail the KBR gravy train. Bases across Iraq remain dependent on the firm’s contractors, and that dependency is only likely to increase as more troops come home. “In essence…we basically said that KBR is too big to fail,” Shays said last May. “So we are still going to fund them.”