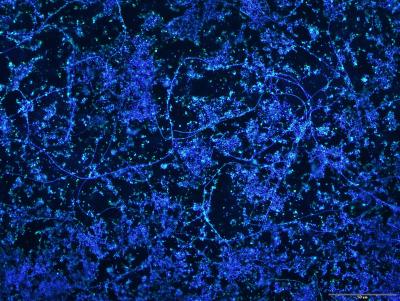

Microbes from the coastal seabed attached to plastic, as seen through a microscope. Credit: Jesse Harrison

Researchers are zeroing in on marine microbes that may help clean up some of the 127 million tons of “disposable” plastic produced every year, 10 percent of which ends up in the ocean. Early research from the University of Sheffield and the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science finds:

- The marine microbe groups that can grow on plastic waste are significantly different from the microbial groups that colonize natural ocean surfaces.

- This suggests that plastic-associated marine microbes have different metabolic activities that could contribute to the breakdown of plastics or of the toxic chemicals associated with them.

This is the first DNA-based study to investigate how microbes interact with plastic. Specifically, the team investigated the attachment of microbes to fragments of polyethylene, the plastic commonly used for shopping bags. They found the plastic was rapidly colonized by multiple—though not every—species of bacteria, which congregated into a biofilm on the surface of the plastic.

Next, they’ll investigate how the microbial interaction with microplastics varies across habitats on coastal seabed—research the team believes could have huge environmental benefits. Researcher Jesse Harrison presented their early findings at the Society for General Microbiology‘s spring meeting in Edinburgh:

“Microbes play a key role in the sustaining of all marine life and are the most likely of all organisms to break down toxic chemicals, or even the plastics themselves. This kind of research is also helping us unravel the global environmental impacts of plastic pollution.”