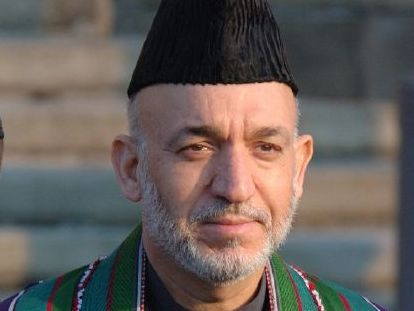

Over the past several years, when he complained again and again about American attacks in his country that were killing civilians in surprising numbers and remarkably often, he was generally humored and dealt with as an irrelevance or an annoyance. Now, given the rampant drug trade, the corruption, the “tantrums,” the emotional outbursts, the threats to join the Taliban, and his embracing of the Iranians and the Chinese, he is dealt with in Washington as a cross between a big baby, an unstable adult, an overemotional drug-taker, and a prime danger to the American project in Afghanistan. He was given a lot of TLC by the previous resident of the White House, while being studiously ignored or reproved by this one. American officials have lavished praise—and scorn—on him. They have brandished hard power—and laid on the soft power—to tame him. They have regularly tried “new tacks” in dealing with him, and then tacked—and tacked again. I’m talking, of course, about Hamid Karzai, the American-installed president of Afghanistan, our man in Kabul, as Alfred McCoy so aptly dubs him. He’s our boy, our nemesis, the definition of our problem in Afghanistan, our worst mistake, and our missing conscience all wrapped in one.

McCoy, a historian at the University of Wisconsin and an expert on the Vietnam War, the CIA, and the drug trade, offers a powerful reminder that we’ve been here before. And he’s not the only one who knows it. After all, Richard Holbrooke, the president’s special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, spent his first six years in government service in, or focused on, Vietnam during the war years. And as the Obama administration was setting its Afghan course in the fall of 2009, a number of key figures in the White House, including the president, took time out to study Gordon Goldstein’s book, Lessons in Disaster: McGeorge Bundy and the Path to War in Vietnam, which recounts, among other things, the grim tale of Ngo Dinh Diem, the Hamid Karzai of that moment, and the CIA plot that led to his overthrow and assassination, as well as a wider, more disastrous war for the US.

As McCoy makes clear, however, the history lesson in all this goes deeper than Karzai and Diem, despite the unbelievably eerie parallels between them. As that old Seinfeld break-up line goes: It’s not you, it’s me. And whatever Karzai’s problems are, it’s not, in the end, him, it’s us. It’s a problem that goes to the riven imperial heart of the matter.