Aiyana Stanley-Jones, pictured in family photograph.

IT WAS JUST AFTER MIDNIGHT on the morning of May 16 and the neighbors say the streetlights were out on Lillibridge Street. It is like that all over Detroit, where whole blocks regularly go dark with no warning or any apparent pattern. Inside the lower unit of a duplex halfway down the gloomy street, Charles Jones, 25, was pacing, unable to sleep.

His seven-year-old daughter, Aiyana Mo’nay Stanley-Jones (PDF), slept on the couch as her grandmother watched television. Outside, Television was watching them. A half-dozen masked officers of the Special Response Team—Detroit’s version of SWAT—were at the door, guns drawn. In tow was an A&E crew filming an episode of The First 48, its true-crime program. The conceit of the show is that homicide detectives have 48 hours to crack a murder case before the trail goes cold. Thirty-four hours earlier, Je’Rean Blake Nobles, 17, had been shot outside a liquor store on nearby Mack Avenue; an informant had ID’d a man named Chauncey Owens as the shooter and provided this address.

The SWAT team tried the steel door to the building. It was unlocked. They threw a flash-bang grenade through the window of the lower unit and kicked open its wooden door, which was also unlocked. The grenade landed so close to Aiyana that it burned her blanket. Officer Joseph Weekley, the lead commando—who’d been featured before on another A&E show, Detroit SWAT—burst into the house. His weapon fired a single shot, the bullet striking Aiyana in the head and exiting her neck. It all happened in a matter of seconds.

“They had time,” a Detroit police detective told me. “You don’t go into a home around midnight. People are drinking. People are awake. Me? I would have waited until the morning when the guy went to the liquor store to buy a quart of milk. That’s how it’s supposed to be done.”

But the SWAT team didn’t wait. Maybe because the cameras were rolling, maybe because a Detroit police officer had been murdered two weeks earlier while trying to apprehend a suspect. This was the first raid on a house since his death.

Police first floated the story that Aiyana’s grandmother had grabbed Weekley’s gun. Then, realizing that sounded implausible, they said she’d brushed the gun as she ran past the door. But the grandmother says she was lying on the far side of the couch, away from the door.

Compounding the tragedy is the fact that the police threw the grenade into the wrong apartment. The suspect fingered for Blake’s murder, Chauncey Owens, lived in the upstairs flat, with Charles Jones’ sister.

Plus, grenades are rarely used when rounding up suspects, even murder suspects. But it was dark. And TV may have needed some pyrotechnics.

“I’m worried they went Hollywood,” said a high-ranking Detroit police official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of the investigation and simmering resentment in the streets. “It is not protocol. And I’ve got to say in all my years in the department, I’ve never used a flash-bang in a case like this.”

The official went on to say that the SWAT team was not briefed about the presence of children in the house, although the neighborhood informant who led homicide detectives to the Lillibridge address told them that children lived there. There were even toys on the lawn.

A dollhouse sits in an empty lot not far from where Aiyana was shot by the police officers storming her home.“It was a total fuck-up,” the official said. “A total, unfortunate fuck-up.”

A dollhouse sits in an empty lot not far from where Aiyana was shot by the police officers storming her home.“It was a total fuck-up,” the official said. “A total, unfortunate fuck-up.”

Owens, a habitual criminal, was arrested upstairs minutes after Aiyana’s shooting and charged for the slaying of Je’Rean. His motive, authorities say, was that the teen failed to pay him the proper respect. Jones, too, later became a person of interest in Je’Rean’s murder—he allegedly went along for the ride—but Jones denies it, and he’s lawyered up and moved to the suburbs.

As Officer Weekley wept on the sidewalk, Aiyana was rushed to the trauma table, where she was pronounced dead. Her body was transferred to the Wayne County morgue.

Dr. Carl Schmidt is the chief medical examiner there. There are at least 50 corpses on hold in his morgue cooler, some unidentified, others whose next of kin are too poor to bury them. So Dr. Schmidt keeps them on layaway, zipped up in body bags as family members wait for a ship to come in that never seems to arrive.

The day I visited, a Hollywood starlet (PDF) was tailing the doctor, studying for her role as the medical examiner in ABC’s new Detroit-based murder drama Detroit 1-8-7. The title is derived from the California penal code for murder: 187. In Michigan, the designation for homicide is actually 750.316 (PDF), but that’s just a mouthful of detail.

“You might say that the homicide of Aiyana is the natural conclusion to the disease from which she suffered,” Schmidt told me.

“What disease was that?” I asked.

“The psychopathology of growing up in Detroit,” he said. “Some people are doomed from birth because their environment is so toxic.”

WAS IT SO SIMPLE? Was it inevitable, as the doctor said, that abject poverty would lead to Aiyana’s death and so many others? Was it death by TV? By police incompetence? By parental neglect? By civic malfeasance? About 350 people are murdered each year in Detroit. There are some 10,000 unsolved homicides dating back to 1960. Many are as fucked up and sad as Aiyana’s. But I felt unraveling this one death could help diagnose what has gone wrong in this city, so I decided to retrace the events leading up to that pitiable moment on the porch on Lillibridge Street.

People my mother’s age like to tell me about Detroit’s good old days of soda fountains and shopping markets and lazy Saturday night drives. But the fact is Detroit and its suburbs were dying 40 years ago. The whole country knew it, and the whole country laughed. A bunch of lazy, uneducated blue-collar incompetents. The Rust Belt. Forget about it.

When I was a teenager, my mother owned a struggling little flower shop on the East Side, not far from where Aiyana was killed. On a hot afternoon around one Mother’s Day, I was working in the back greenhouse. It was a sweatbox, and I went across the street to the liquor store for a soda pop. A small crowd of agitated black people was gathered on the sidewalk. The store bell jingled its little requiem as I pulled the door open.

Inside, splayed on the floor underneath the rack of snack cakes near the register, was a black man in a pool of blood. The blood was congealing into a pancake on the dirty linoleum. His eyes and mouth were open and held that milky expression of a drunk who has fallen asleep with his eyes open. The red halo around his skull gave the scene a feeling of serenity.

An Arab family owned the store, and one of the men—the one with the pocked face and loud voice—was talking on the telephone, but I remember no sounds. His brother stood over the dead man, a pistol in his hand, keeping an eye on the door in case someone walked in wanting to settle things.

“You should go,” he said to me, shattering the silence with a wave of his hand. “Forget what you saw, little man. Go.” He wore a gold bracelet as thick as a gymnasium rope. I lingered a moment, backing out while taking it in: the bracelet, the liquor, the blood, the gun, the Ho-Hos, the cheapness of it all.

The flower shop is just a pile of bricks now, but despite what the Arab told me, I did not forget what I saw. Whenever I see a person who died of violence or misadventure, I think about the dead man with the open eyes on the dirty floor of the liquor store. I’ve seen him in the faces of soldiers when I was covering the Iraq War. I saw him in the face of my sister, who died a violent death in a filthy section of Detroit a decade ago. I saw him in the face of my sister’s daughter, who died from a heroin overdose in a suburban basement near the interstate, weeks after I moved back to Michigan with my wife to raise our daughter and take a job with the Detroit News.

No one cared much about Detroit or its industrial suburbs until the Dow collapsed, the chief executives of the Big Three went to Washington to grovel, and General Motors declared bankruptcy—100 years after its founding. Suddenly, Detroit was historic, symbolic—hip, even. I began to get calls from reporters around the world wondering what Detroit was like, what was happening here. They were wondering if the Rust Belt cancer had metastasized and was creeping to Los Angeles and London and Barcelona. Was Detroit an outlier or an epicenter?

JE’REAN BLAKE NOBLES was one of the rare black males in Detroit who made it (PDF) through high school. A good kid with average grades, Je’Rean went to Southeastern High, which is situated in an industrial belt of moldering Chrysler assembly plants. Completed in 1917, the school, attended by white students at the time, was considered so far out in the wilds that its athletic teams took the nickname “Jungaleers.”

Lyvonne Cargill wears a shirt that honors her son, Je’Rean Blake Nobles. His murder led to the police raid that killed Aiyana.With large swaths of the city rewilding—empty lots are returning to prairie and woodland as the city depopulates—Southeastern was slated to absorb students from nearby Kettering High this year as part of a massive school-consolidation effort. That is, until someone realized that the schools are controlled by rival gangs. So bad is the rivalry that when the schools face off to play football or basketball, spectators from the visiting team are banned.

Lyvonne Cargill wears a shirt that honors her son, Je’Rean Blake Nobles. His murder led to the police raid that killed Aiyana.With large swaths of the city rewilding—empty lots are returning to prairie and woodland as the city depopulates—Southeastern was slated to absorb students from nearby Kettering High this year as part of a massive school-consolidation effort. That is, until someone realized that the schools are controlled by rival gangs. So bad is the rivalry that when the schools face off to play football or basketball, spectators from the visiting team are banned.

Southeastern’s motto is Age Quod Agis: “Attend to Your Business.” And Je’Rean did. By wit and will, he managed to make it through. A member of JROTC, he was on his way to the military recruitment office after senior prom and commencement. But Je’Rean never went to prom, much less the Afghanistan theater, because he couldn’t clear the killing fields of Detroit. He became a horrifying statistic—one of 103 kids and teens murdered between January 2009 and July 2010.

Je’Rean’s crime? He looked at Chauncey Owens the wrong way, detectives say.

It was 2:40 in the afternoon on May 14 when Je’Rean went to the Motor City liquor store and ice-cream stand to get himself an orange juice to wash down his McDonald’s. About 40 kids were milling around in front of the soft-serve window. That’s when Owens, 34, pulled up on a moped.

Je’Rean might have thought it was funny to see a grown man driving a moped. He might have smirked. But according to a witness, he said nothing.

“Why you looking at me?” said Owens, getting off the moped. “Do you got a problem or something? What the fuck you looking at?”

A slender, pimply faced kid, Je’Rean was not an intimidating figure. One witness had him pegged for 13 years old.

Je’Rean balled up his tiny fist. “What?” he croaked.

“Oh, stay your ass right here,” Owens growled. “I got something for you.”

Owens sped two blocks back to Lillibridge and gathered up a posse, according to his statement to the police. The posse allegedly included Aiyana’s father, Charles “C.J.” Jones.

“It’s some lil niggas at the store talking shit—let’s go whip they ass,” Detective Theopolis Williams later testified that Owens told him during his interrogation.

Owens switched his moped for a Chevy Blazer. Jones and two other men known as “Lil’ James” and “Dirt” rode along for Je’Rean’s ass-whipping. Lil’ James brought along a .357 Magnum—at the behest of Jones, Detective Williams testified, because Jones was afraid someone would try to steal his “diamond Cartier glasses.”

Je’Rean knew badness was on its way and called his mother to come pick him up. She arrived too late. Owens got there first and shot Je’Rean clear through the chest with Lil’ James’ gun. Clutching his juice in one hand and two dollars in the other, Je’Rean staggered across Mack Avenue and collapsed in the street. A minute later, a friend took the two dollars as a keepsake. A few minutes after that, Je’Rean’s mother, Lyvonne Cargill, arrived and got behind the wheel of the car that friends had dragged him into.

Why would anyone move a gunshot victim, much less toss him in a car? It is a matter of conditioning, Cargill later told me. In Detroit, the official response time of an ambulance to a 911 call is 12 minutes. Paramedics say it is routinely much longer. Sometimes they come in a Crown Victoria with only a defibrillator and a blanket, because there are no other units available. The hospital was six miles away. Je’Rean’s mother drove as he gurgled in the backseat. [CLICK HERE FOR CHARLIE LEDUFF’S EXPOSE ON THE DETROIT AMBULANCE SYSTEM.]

“My baby, my baby, my baby. God, don’t take my baby.”

They made it to the trauma ward, where Je’Rean was pronounced dead. His body was transferred to Dr. Schmidt and the Wayne County morgue.

Unclaimed bodies at the Wayne County MorgueTHE RAID ON THE Lillibridge house that took little Aiyana’s life came two weeks and at least a dozen homicides after the last time police stormed into a Detroit home. That house, too, is on the city’s East Side, a nondescript brick duplex with a crumbling garage whose driveway funnels into busy Schoenherr Road.

Unclaimed bodies at the Wayne County MorgueTHE RAID ON THE Lillibridge house that took little Aiyana’s life came two weeks and at least a dozen homicides after the last time police stormed into a Detroit home. That house, too, is on the city’s East Side, a nondescript brick duplex with a crumbling garage whose driveway funnels into busy Schoenherr Road.

Responding to a breaking-and-entering and shots-fired call at 3:30 a.m., Officer Brian Huff, a 12-year veteran, walked into that dark house. Behind him stood two rookies. His partner took the rear entrance. Huff and his partner were not actually called to the scene; they’d taken it upon themselves to assist the younger cops, according to the police version of events. Another cruiser with two officers responded as well.

Huff entered with his gun still holstered. Behind the door was Jason Gibson, 25, a violent man with a history of gun crimes, assaults on police, and repeated failures to honor probationary sentences.

Gibson is a tall, thick-necked man who, like the character Omar from The Wire, made his living robbing dope houses. Which is what he was doing at this house, authorities contend, when he put three bullets in Officer Huff’s face.

What happened after that is a matter of conjecture, as Detroit officials have had problems getting their stories straight. Neighbor Paul Jameson, a former soldier whose wife had called in the break-in to 911, said the rookies ran toward the house and opened fire after Huff was shot.

Someone radioed in, and more police arrived—but the official story of what happened that night has changed repeatedly. First, it was six cops who responded to the 911 call. Then eight, then eleven. Officials said Gibson ran out the front of the house. Then they said he ran out the back of the house, even though there is no back door. Then they said he jumped out a back window. It was Jameson who finally dragged Huff out of the house and gave him CPR in the driveway, across the street from the Boys & Girls Club. In the end, Gibson was charged with Huff’s murder and the attempted murders of four more officers. But police officials have refused to discuss how one got shot in the foot.

“We believe some of them were struck by friendly fire,” the high-ranking cop told me. “But our ammo’s so bad, we can’t do ballistics testing. We’ve got nothing but bullet fragments.”

A neighbor who tends the lawn in front of the dope house out of respect to Huff wonders why so many cops came in the first place, given that “the police hardly come around at all, much less that many cops that fast on a home break-in.”

But the real mystery behind Officer Huff’s murder is why Gibson was out on the street in the first place. In 2007, he attacked a cop and tried to take his gun. For that he was given simple probation. He failed to report. Police caught him again in November 2009 in possession of a handgun stolen from an Ohio cop. Gibson bonded out last January and actually showed up for his trial in circuit court on February 17.

A wary Detroit police officer keeps watch over an unruly crowd after an arrest on the East Side.The judge, Cynthia Gray Hathaway, set his bond at $20,000—only 10 percent of which was due upfront—and adjourned the trial without explanation, according to the docket. Known as “Half-Day” Hathaway, the judge was removed from the bench for six months by the Michigan Supreme Court a decade ago for, among other things, adjourning trials to sneak away on vacation.

A wary Detroit police officer keeps watch over an unruly crowd after an arrest on the East Side.The judge, Cynthia Gray Hathaway, set his bond at $20,000—only 10 percent of which was due upfront—and adjourned the trial without explanation, according to the docket. Known as “Half-Day” Hathaway, the judge was removed from the bench for six months by the Michigan Supreme Court a decade ago for, among other things, adjourning trials to sneak away on vacation.

Predictably, Gibson did not show for his new court date. The day after Huff was killed, and under fire from the police for her leniency toward Gibson, Judge Hathaway went into the case file and made changes, according to notations made in the court’s computerized docket system. She refused to let me see the original paper file, despite the fact that it is a public record, and has said that she can’t comment on the case because she might preside in the trial against Gibson.

More than 4,000 people attended Officer Huff’s funeral at the Greater Grace Temple on the city’s Northwest Side. Police officers came from Canada and across Michigan. They were restless and agitated and pulled at the collars of dress blues that didn’t seem to fit. Bagpipes played and the rain fell.

Mayor Dave Bing spoke. “The madness has to stop,” he said.

But the madness was only beginning.

IT MIGHT BE a stretch to see anything more than Detroit’s problems in Detroit’s problems. Still, as the American middle class collapses, it’s worth perhaps remembering that the East Side of Detroit—the place where Aiyana, Je’Rean, and Officer Huff all died—was once its industrial cradle.

Henry Ford built his first automobile assembly-line plant in Highland Park in 1908 on the east side of Woodward Avenue, the thoroughfare that divides the east of Detroit from the west. Over the next 50 years, Detroit’s East Side would become the world’s machine shop, its factory floor. The city grew to 1.3 million people from 300,000 after Ford opened his Model T factory. Other auto plants sprang up on the East Side: Packard, Studebaker, Chrysler’s Dodge Main. Soon, the Motor City’s population surpassed that of Boston and Baltimore, old East Coast port cities founded on maritime shipping when the world moved by boat.

European intellectuals wondered at the whirl of building and spending in the new America. At the center of this economic dynamo was Detroit. “It is the home of mass-production, of very high wages and colossal profits, of lavish spending and reckless instalment-buying, of intense work and a large and shifting labour-surplus,” British historian and MP Ramsay Muir wrote in 1927. “It regards itself as the temple of a new gospel of progress, to which I shall venture to give the name of ‘Detroitism’.”

Skyscrapers sprang up virtually overnight. The city filled with people from all over the world: Arabs, Appalachians, Poles, African Americans, all in their separate neighborhoods surrounding the factories. Forbidden by restrictive real estate covenants and racist custom, the blacks were mostly restricted to Paradise Valley, which ran the length of Woodward Avenue. As the black population grew, so did black frustration over poor housing and rock-fisted police.

Soon, the air was the color of a filthy dishrag. The water in the Detroit River was so bad, it was said you could bottle it and sell it as poison. The beavers disappeared from the river around 1930.

But pollution didn’t kill Detroit. What did?

No one can answer that fully. You can blame it on the John Deere mechanical cotton-picker of 1950, which uprooted the sharecropper and sent him north looking for a living—where he found he was locked out of the factories by the unions. You might blame it on the urban renewal and interstate highway projects that rammed a freeway down the middle of Paradise Valley, displacing thousands of blacks and packing the Negro tenements tighter still. (Thomas Sugrue, in his seminal book The Origins of the Urban Crisis, writes that residents in Detroit’s predominantly black lower East Side reported 206 rat bites in 1951 and 1952.)

You might blame postwar industrial policies that sent the factories to the suburbs, the rural South, and the western deserts. You might blame the 1967 race riot and the white flight that followed. You might blame Coleman Young—the city’s first black mayor—and his culture of cronyism. You could blame it on the gas shocks of the ’70s that opened the door to foreign car competition. You might point to the trade agreements of the Clinton years, which allowed American manufacturers to leave the country by the back door. You might blame the UAW, which demanded things like full pay for idle workers, or myopic Big Three management who, instead of saying no, simply tacked the cost onto the price of a car.

Then there is the thought that Detroit is simply a boomtown that went bust the minute Henry Ford began to build it. The car made Detroit, and the car unmade Detroit. The auto industry allowed for sprawl. It also allowed a man to escape the smoldering city.

The Packard plant, where we came across this “fashion shoot,” has been smoldering for decades.In any case, Detroit began its long precipitous decline during the 1950s, precisely when the city—and the United States—was at its peak. As Detroit led the nation in median income and homeownership, automation and foreign competition were forcing companies like Packard to shutter their doors. That factory closed in 1956 and was left to rot, pulling down the East Side, which pulled down the city. Inexplicably, its carcass still stands and burns incessantly.

The Packard plant, where we came across this “fashion shoot,” has been smoldering for decades.In any case, Detroit began its long precipitous decline during the 1950s, precisely when the city—and the United States—was at its peak. As Detroit led the nation in median income and homeownership, automation and foreign competition were forcing companies like Packard to shutter their doors. That factory closed in 1956 and was left to rot, pulling down the East Side, which pulled down the city. Inexplicably, its carcass still stands and burns incessantly.

By 1958, 20 percent of the Detroit workforce was jobless. Not to worry: The city had its own welfare system, decades before Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. The city provided clothing, fuel, rent, and $10 every week to adults for food; children got $5. Word of the free milk and honey made its way down South, and the poor “Negros” and “hillbillies” flooded in.

But if it wasn’t for them, the city population would have sunk further than it did. Nor is corruption a black or liberal thing. Louis Miriani, the last Republican mayor of Detroit, who served from 1957 to 1962, was sent to federal prison for tax evasion when he couldn’t explain how he made nearly a quarter of a million dollars on a reported salary of only $25,000.

Today—75 years after the beavers disappeared from the Detroit River—”Detroitism” means something completely different. It means uncertainty and abandonment and psychopathology. The city reached a peak population of 1.9 million people in the 1950s, and it was 83 percent white. Now Detroit has fewer than 800,000 people, is 83 percent black, and is the only American city that has surpassed a million people and dipped back below that threshold.

“There are plenty of good people in Detroit,” boosters like to say. And there are. Tens of thousands of them, hundreds of thousands. There are lawyers and doctors and auto executives with nice homes and good jobs, community elders trying to make things better, teachers who spend their own money on classroom supplies, people who mow lawns out of respect for the dead, parents who raise their children, ministers who help with funeral expenses.

For years it was the all-but-official policy of the newspapers to ignore the black city, since the majority of readers lived in the predominantly white suburbs. And now that the papers do cover Detroit, boosters complain about a lack of balance. To me, that’s like writing about the surf conditions in the Gaza Strip. As for the struggles of a generation of living people, the murder of a hundred children, they ask me: “What’s new in that?”

DETROIT’S EAST SIDE is now the poorest, most violent quarter of America’s poorest, most violent big city. The illiteracy, child poverty, and unemployment rates hover around 50 percent.

Testifying at the New Prospect Missionary Baptist Church.Stand at the corner of Lillibridge Street and Mack Avenue and walk a mile in each direction from Alter Road to Gratiot Avenue (pronounced Gra-shit). You will count 34 churches, a dozen liquor stores, six beauty salons and barber shops, a funeral parlor, a sprawling Chrysler engine and assembly complex working at less than half-capacity, and three dollar stores—but no grocery stores. In fact, there are no chain grocery stores in all of Detroit.

Testifying at the New Prospect Missionary Baptist Church.Stand at the corner of Lillibridge Street and Mack Avenue and walk a mile in each direction from Alter Road to Gratiot Avenue (pronounced Gra-shit). You will count 34 churches, a dozen liquor stores, six beauty salons and barber shops, a funeral parlor, a sprawling Chrysler engine and assembly complex working at less than half-capacity, and three dollar stores—but no grocery stores. In fact, there are no chain grocery stores in all of Detroit.

There are two elementary schools in the area, both in desperate need of a lawnmower and a can of paint. But there is no money; the struggling school system has a $363 million deficit. Robert Bobb was hired in 2009 as the emergency financial manager and given sweeping powers to balance the books. But even he couldn’t stanch the tsunami of red ink; the deficit ballooned more than $140 million under his guidance.

Bobb did uncover graft and fraud and waste, however. He caught a lunch lady stealing the children’s milk money. A former risk manager for the district was indicted for siphoning off $3 million for personal use. The president of the school board, Otis Mathis, recently admitted that he had only rudimentary writing skills shortly before being forced to resign for fondling himself during a meeting with the school superintendent.

The graduation rate for Detroit schoolkids hovers around 35 percent (PDF). Moreover, the Detroit public school system is the worst performer in the National Assessment of Educational Progress tests, with nearly 80 percent of eighth-graders unable to do basic math. So bad is it for Detroit’s children that Education Secretary Arne Duncan said last year, “I lose sleep over that one.”

These girls are the lucky ones. In Detroit, only 1 in 3 kids will graduate from high school. Almost half of all adults are illiterate.Duncan may lie awake, but many civic leaders appear to walk around with their eyes sealed shut. As a reporter, I’ve worked from New York to St. Louis to Los Angeles, and Detroit is the only big city I know of that doesn’t put out a crime blotter tracking the day’s mayhem. While other American metropolises have gotten control of their murder rate, Detroit’s remains where it was during the crack epidemic. Add in the fact that half the police precincts were closed in 2005 for budgetary reasons, and the crime lab was closed two years ago due to ineptitude, and it might explain why five of the nine members of the city council carry a firearm.

These girls are the lucky ones. In Detroit, only 1 in 3 kids will graduate from high school. Almost half of all adults are illiterate.Duncan may lie awake, but many civic leaders appear to walk around with their eyes sealed shut. As a reporter, I’ve worked from New York to St. Louis to Los Angeles, and Detroit is the only big city I know of that doesn’t put out a crime blotter tracking the day’s mayhem. While other American metropolises have gotten control of their murder rate, Detroit’s remains where it was during the crack epidemic. Add in the fact that half the police precincts were closed in 2005 for budgetary reasons, and the crime lab was closed two years ago due to ineptitude, and it might explain why five of the nine members of the city council carry a firearm.

To avoid the embarrassment of being the nation’s perpetual murder capital, the police department took to cooking the homicide statistics, reclassifying murders as other crimes or incidents. For instance, in 2008 a man was shot in the head. ME Schmidt ruled it a homicide; the police decided it was a suicide. That year, the police said there were 306 homicides—until I began digging. The number was actually 375. I also found that the police and judicial systems were so broken that in more than 70 percent of murders, the killer got away with it. In Los Angeles, by comparison, the unsolved-murder rate is 22 percent.

The fire department is little better. When I moved back to Detroit two years ago, I profiled a firehouse on the East Side. Much of the firefighters’ equipment was substandard: Their boots had holes; they were alerted to fires by fax from the central office. (They’d jerry-rigged a contraption where the fax pushes a door hinge, which falls on a screw wired to an actual alarm.) I called the fire department to ask for its statistics. They’d not been tabulated for four years.

Shoddily equipped firemen face some 500 arsons a month.Detroit has been synonymous with arson since the ’80s, when the city burst into flames in a pre-Halloween orgy of fire and destruction known as Devil’s Night. At its peak popularity, 810 fires were set in a three-day span. Devil’s Night is no longer the big deal it used to be, topping out last year at around 65 arsons. That’s good news until you realize that in Detroit, some 500 fires are set every single month. That’s five times as many as New York, in a city one-tenth the size.

Shoddily equipped firemen face some 500 arsons a month.Detroit has been synonymous with arson since the ’80s, when the city burst into flames in a pre-Halloween orgy of fire and destruction known as Devil’s Night. At its peak popularity, 810 fires were set in a three-day span. Devil’s Night is no longer the big deal it used to be, topping out last year at around 65 arsons. That’s good news until you realize that in Detroit, some 500 fires are set every single month. That’s five times as many as New York, in a city one-tenth the size.

As a reporter at the Detroit News, I get plenty of phone calls from people in the neighborhoods. A man called me once to say he had witnessed a murder, but the police refused to take his statement. When I called the head of the homicide bureau and explained the situation, he told me, “Oh yeah? Have him call me,” and then hung up the phone. One man, who wanted to turn himself in for a murder, gave up trying to call the Detroit police; he drove to Ohio and turned himself in there.

The police have been working under a federal consent decree since a 2003 investigation found that detectives were locking up murder witnesses for days on end, without access to a lawyer, until they coughed up a name. The department was also cited for excessive force after people died in lockup and at the hands of rogue cops.

Detroit has since made little progress on the federal consent decree. Newspapers made little of it—until the US Attorney revealed that the federal monitor of the decree was having an affair with the priapic mayor Kwame Kilpatrick, who was forced to resign, and now sits in prison convicted of perjury and obstruction of justice.

The Kilpatrick scandal, combined with the murder rate, spurred the newly elected mayor, Dave Bing—an NBA Hall of Famer—to fire Police Chief James Barrens last year and replace him with Warren Evans, the Wayne County sheriff. The day Barrens cleaned out his desk, a burglar cleaned out Barrens’ house.

Evans brought a refreshing honesty to a department plagued by ineptitude and secrecy. He computerized daily crime statistics, created a mobile strike force commanded by young and educated go-getters, and dispatched cops to crime hot spots. He assigned the SWAT team the job of rounding up murder suspects, a task that had previously been done by detectives.

Evans told me then that major crimes were routinely underreported by 20 percent. He also told me that perhaps 50 percent of Detroit’s drivers were operating without a license or insurance. “It’s going to stop,” he promised. “We’re going to pull people over for traffic violations and we’re going to take their cars if they’re not legal. That’s one less knucklehead driving around looking to do a drive-by.”

His approach was successful, with murder dropping more than 20 percent in his first year. If that isn’t a record for any major metropolis, it is certainly a record for Detroit. (And that statistic is true; I checked.)

So there should have been a parade with confetti and tanks of lemonade, but instead, the complaints about overaggressive cops began to roll in. Then Evans’ own driver shot a man last October. The official version was that two men were walking in the middle of a street on the East Side when Evans and his driver told them to walk on the sidewalk. One ran off. Evans’ driver—a cop—gave chase. The man stopped, turned, and pulled a gun. Evans’ driver dropped him with a single shot. An investigation was promised. The story rated three paragraphs in the daily papers, and the media never followed up. Then Huff got killed. Then Je’Rean was murdered. Then came the homicide-by-cop of little Aiyana.

Chief Evans might have survived it all, had he, too, not been drawn to the lights of Hollywood. As it turns out, he was filming a pilot for his own reality show, entitled The Chief.

The program’s six-minute sizzle reel begins with Evans dressed in full battle gear in front of the shattered Michigan Central Rail Depot, cradling a semiautomatic rifle and declaring that he would “do whatever it takes” to take back the streets of Detroit. I saw the tape and wrote about its existence after the killing of Aiyana, but the story went nowhere until two months later, when someone in City Hall leaked a copy to the local ABC affiliate. Evans was fired.

But in Evans’ defense, he seemed to understand one thing: After the collapse of the car industry and the implosion of the real estate bubble, there is little else Detroit has to export except its misery.

And America is buying. There are no fewer than two TV dramas, two documentaries, and three reality programs being filmed here. Even Time bought a house on the East Side last year for $99,000. The gimmick was to have its reporters live there and chronicle the decline of the Motor City for one year.

Somebody should have told company executives back in New York that they had wildly overpaid. In Detroit, a new car costs more than the average house.

AIYANA’S FAMILY retained Geoffrey Fieger, the flamboyant, brass-knuckled lawyer who represented Dr. Jack Kevorkian—a.k.a. Dr. Death. With Chief Evans vacationing overseas with a subordinate, Fieger ran wild, holding a press conference where he claimed he had seen videotape of Officer Weekley firing into the house from the porch. Fieger alleged a police cover-up. Detroit grew restless.

I went to see Fieger to ask him to show me the tape. Fieger’s suburban office is a shrine to Geoffrey Fieger. The walls are covered with photographs of Geoffrey Fieger. On his desk is a bronze bust of Geoffrey Fieger. And during our conversation, he referred to himself in the third person—Geoffrey Fieger.

“What killed Aiyana is what killed the people in New Orleans and the rider on the transit in Oakland, and that’s police bullets and police arrogance and police cover-up,” Geoffrey Fieger said. “People call it police brutality. But Geoffrey Fieger calls it police arrogance. Even in Detroit, a predominantly black city. They killed a child and then they lied about it.”

I asked Fieger if Charles Jones should accept some culpability in his daughter’s death, considering his alleged role in Je’Rean’s murder, the stolen cars found in his backyard, and the fact that his daughter slept on the couch next to an unlocked door.

“So what?” Fieger barked. “I’m not representing the father; I’m speaking for the daughter.” He also pointed out that while Jones remains a person of interest in Je’Rean’s murder, he has not been arrested. “It’s police disinformation.”

As for the videotape of the killing, Geoffrey Fieger said he did not have it.

I was allowed to meet with Charles Jones the following morning at Fieger’s office, but with the caveat that I could only ask him questions about the evening his daughter was killed.

Jones, 25, a slight man with frizzy braids, wore a dingy T-shirt. An 11th-grade dropout and convicted robber, he said he supported his seven children with “a little this, a little that—I got a few tricks and trades.”

He has three boys with Aiyana’s mother, Dominika Stanley, and three boys with another woman, whom he had left long ago.

Jones’ new family had been on the drift for the past few years as he tried to pull it together. His mother’s house on Lillibridge, he said, was just supposed to be a way station to better things.

They had even kept Aiyana in her old school, Trix Elementary, because it was something consistent in her life, a clean and safe school in a city with too few. They drove her there every morning, five miles.

“I can accept the shooting was a mistake,” Jones said about his daughter’s death as a bleary-eyed Stanley sat motionless next to him. “But I can’t accept it because they lied about it. I can’t heal properly because of it. It was all for the cameras. I don’t want no apology from no police. It’s too late.”

I asked him if the way he was raising his daughter, the people he exposed her to, or the neighborhood where they lived—with its decaying houses and liquor stores—may have played a role.

Stanley suddenly emerged from her stupor: “What’s that got to do with it?” she hissed.

“My daughter got love, honor, and respect. The environment didn’t affect us none,” Jones said. “The environment got nothing to do with kids.”

A makeshift memorial on Aiyana’s porch.

A makeshift memorial on Aiyana’s porch.

AIYANA WAS LAID TO REST six days after her killing. The service was held at Second Ebenezer Church in Detroit, a drab cake-shaped megachurch near the Chrysler Freeway. A thousand people attended, as did the predictable plump of media.

The Rev. Al Sharpton delivered the eulogy, though his heart did not seem to be in it. It was a white cop who killed the girl, but Detroit is America’s largest black city with a black mayor and a black chief of police. The sad and confusing circumstances of the murders of Je’Rean Blake and Officer Huff, both black, robbed Sharpton of some of his customary indignation.

“We’re here today not to find blame, but to find out how we never have to come here again,” said Sharpton, standing in the grand pulpit. “It’s easy in our anger, our rage, to just vent and scream. But I would be doing Aiyana a disservice if we just vented instead of dealing with the real problems.”

He went on: “This child is the breaking point.”

Aiyana’s pink-robed body was carried away by a horse-drawn carriage to the Trinity Cemetery, the same carriage that five years earlier had taken the body of Rosa Parks to Woodlawn Cemetery on the city’s West Side. Once at Aiyana’s graveside, Charles Jones released a dove.

Sharpton left and the Rev. Horace Sheffield, a local version of Sharpton, got stiffed for $4,000 in funeral costs, claiming Aiyana’s father made off with the donations people gave to cover it.

“I’m trying to find him,” Sheffield complained. “But he doesn’t return my calls. It’s always like that. People taking advanage of my benevolence. They went hog wild. I mean, hiring the Rosa Parks carriage?”

“I don’t owe Sheffield shit,” says Jones. “He got paid exactly what he was supposed to be paid.”

While a thousand people mourned the tragic death of Aiyana, the body of Je’Rean Blake Nobles sat in a refrigerator at a local funeral parlor; his mother was too poor to bury him herself and too respectful to bury him until after the little girl’s funeral, anyhow. The mortician charged $700 for the most basic viewing casket, even though the body was to be cremated.

Sharpton’s people called Je’Rean’s mother, Lyvonne Cargill, promising to come over to her house after Aiyana’s funeral. She waited, but Sharpton never came.

“Sharpton’s full of shit,” said Cargill, a brassy 39-year-old who works as a stock clerk at Target. “He came here for publicity. He’s from New York. What the hell you doing up here for? The kids are dropping like flies—especially young black males—and he’s got nothing but useless words.”

The Rev. Sheffield came to see Cargill. He gave her $800 for funeral costs.

AS SUMMER DRAGGED on, the story of Aiyana faded from even the regional press. As for the tape that Geoffrey Fieger claimed would show the cops firing on Aiyana’s house from outside, A&E turned it over to the police. The mayor’s office is said to have a copy, as well as the Michigan State Police, who are now handling the investigation. Even on Lillibridge Street, the outrage has died down. But the people of Lillibridge Street still look like they’ve been picked up by their hair and dropped from the rooftop. The crumbling houses still crumble. The streetlights still go on and off. The landlord of the duplex, Edward Taylor, let me into the Jones apartment. A woman was in his car, the motor running.

“They still owe me rent,” he said with a face about the Joneses. “Don’t bother locking it. It’s now just another abandoned house in Detroit.”

And with that, he was off.

Inside, toys, Hannah Montana shoes, and a pyramid of KFC cartons were left to rot. The smell was beastly. Outside, three men were loading the boiler, tubs, and sinks into a trailer to take to the scrap yard.

“Would you take a job at that Chrysler plant if there were any jobs there?” I asked one of the men, who was sweating under the weight of the cast iron.

“What the fuck do you think?” he said. “Of course I would. Except there ain’t no job. We’re taking what’s left.”

I went to visit Cargill, who lived just around the way. She told me that Je’Rean’s best friend Chaise Sherrors, 17, had been murdered the night before—an innocent bystander who took a bullet in the head as he was on a porch clipping someone’s hair.

“It just goes on,” she said. “The silent suffering.”

Funeral for Chaise Sherrors, Je’Rean’s best friend. Sherrors was killed by a stray bullet while cutting a friend’s hair on a front porch just 27 days after Je’Rean died. Sherrors’ mom, in white, lost another son to a bullet the previous year. Both sons now sit in urns on her mantel.Chaise lived on the other side of the Chrysler complex. He, too, was about to graduate from Southeastern High. A good kid who showed neighborhood children how to work electric clippers, his dream was to open a barbershop. The morning after he was shot, Chaise’s clippers were mysteriously deposited on his front porch, wiped clean and free of hair. There was no note.

Funeral for Chaise Sherrors, Je’Rean’s best friend. Sherrors was killed by a stray bullet while cutting a friend’s hair on a front porch just 27 days after Je’Rean died. Sherrors’ mom, in white, lost another son to a bullet the previous year. Both sons now sit in urns on her mantel.Chaise lived on the other side of the Chrysler complex. He, too, was about to graduate from Southeastern High. A good kid who showed neighborhood children how to work electric clippers, his dream was to open a barbershop. The morning after he was shot, Chaise’s clippers were mysteriously deposited on his front porch, wiped clean and free of hair. There was no note.

If such a thing could be true, Chaise’s neighborhood is worse than Je’Rean’s. The house next door to his is rubble smelling of burnt pine, pissed on by the spray cans of the East Warren Crips. The house on the other side is in much the same state. So is the house across the street. In this shit, a one-year-old played next door, barefoot.

Chaise’s mother, Britta McNeal, 39, sat on the porch staring blankly into the distance, smoking no-brand cigarettes. She thanked me for coming and showed me her home, which was clean and well kept. Then she introduced me to her 14-year-old son De’Erion, whose remains sat in an urn on the mantel. He was shot in the head and killed last year.

She had already cleared a space on the other end of the mantel for Chaise’s urn.

“That’s a hell of a pair of bookends,” I offered.

“You know? I was thinking that,” she said with tears.

Parts of the Detroit River are now clean enough for swimming. Even the beavers have returned.The daughter of an autoworker and a home nurse, McNeal grew up in the promise of the black middle class that Detroit once offered. But McNeal messed upÐshe admits as much. She got pregnant at 15. She later went to nursing school but got sidetracked by her own health problems. School wasn’t a priority. Besides, there was always a job in America when you needed one.

Parts of the Detroit River are now clean enough for swimming. Even the beavers have returned.The daughter of an autoworker and a home nurse, McNeal grew up in the promise of the black middle class that Detroit once offered. But McNeal messed upÐshe admits as much. She got pregnant at 15. She later went to nursing school but got sidetracked by her own health problems. School wasn’t a priority. Besides, there was always a job in America when you needed one.

Until there wasn’t. Like so many across the country, she’s being evicted with no job and no place to go.

“I want to get out of here, but I can’t,” she said. “I got no money. I’m stuck. Not all of us are blessed.”

She looked at her barefoot grandson playing in the wreckage of the dwelling next door and wondered if he would make it to manhood.

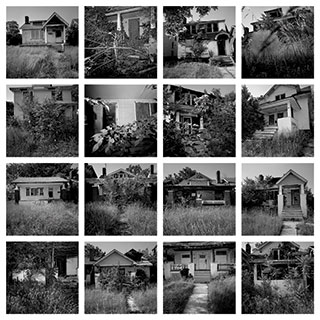

Some 45,000 abandoned houses pock Detroit. The ones pictured here are all found on one block. Detroit demolishes only 500 homes a year, thanks to concerns over lawsuits and environmental hazards, as well as lack of funds and ineptitude. [CHECK OUT A SLIDESHOW OF ABANDONED HOUSES ON ONE BLOCK IN DETROIT]“I keep calling about these falling-down houses, but the city never comes,” she said.

Some 45,000 abandoned houses pock Detroit. The ones pictured here are all found on one block. Detroit demolishes only 500 homes a year, thanks to concerns over lawsuits and environmental hazards, as well as lack of funds and ineptitude. [CHECK OUT A SLIDESHOW OF ABANDONED HOUSES ON ONE BLOCK IN DETROIT]“I keep calling about these falling-down houses, but the city never comes,” she said.

McNeal wondered how she was going to pay the $3,000 for her son’s funeral. Desperation, she said, feels like someone’s reaching down your throat and ripping out your guts.

It would be easy to lay the blame on McNeal for the circumstances in which she raised her sons. But is she responsible for police officers with broken computers in their squad cars, firefighters with holes in their boots, ambulances that arrive late, a city that can’t keep its lights on and leaves its vacant buildings to the arsonist’s match, a state government that allows corpses to stack up in the morgue, multinational corporations that move away and leave poisoned fields behind, judges who let violent criminals walk the streets, school stewards who steal the children’s milk money, elected officials who loot the city, automobile executives who couldn’t manage a grocery store, or Wall Street grifters who destroyed the economy and left the nation’s children with a burden of debt? Can she be blamed for that?

“I know society looks at a person like me and wants me to go away,” she said. “‘Go ahead, walk in the Detroit River and disappear.’ But I can’t. I’m alive. I need help. But when you call for help, it seems like no one’s there.

“It feels like there ain’t no love no more.”

I left McNeal’s porch and started my car. The radio was tuned to NPR and A Prairie Home Companion came warbling out of my speakers. I stared through the windshield at the little boy in the diaper playing amid the ruins, reached over, and switched it off.

Editors’ note: On October 4, 2011, following a yearlong investigation by the Michigan state police, Officer Weekley was charged with involuntary manslaughter and careless discharge of a firearm. The First 48 photographer Allison Howard was charged with perjury and obstruction of justice. The Detroit Free Press has more details here. On April 4, 2019, Aiyana’s family settled with Detroit for $8.25 million.

Charlie LeDuff is a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, filmmaker, and multimedia reporter. He was formerly a reporter for The Detroit News.

Danny Wilcox Frazier is a contributing photographer for Mother Jones. His work has appeared in Time, Life, and Newsweek.