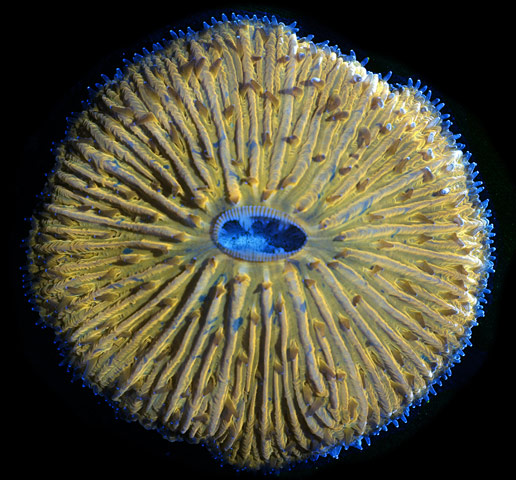

Close-up of live mushroom coral taken by James Nicholson of the Coral Culture and Collaborative Research Facility, South Carolina. This image took 13th place at the 2010 Nikon Small World Photgraphy Contest. To read about a renowned mycologist’s quest for a mushroom that could save the world, click here. For more mushroom photos, click here.

Close-up of live mushroom coral taken by James Nicholson of the Coral Culture and Collaborative Research Facility, South Carolina. This image took 13th place at the 2010 Nikon Small World Photgraphy Contest. To read about a renowned mycologist’s quest for a mushroom that could save the world, click here. For more mushroom photos, click here.

Mushroom corals are members of the Fungiidae, a family of interesting marine animals in the phylum Cnidaria, which includes corals, anemones, and jellyfish, as well as some aquatic species. Unlike the more familiar stony, or reef-building corals, most mushroom corals are not polyps roughly the size of ants living together in colonies that take the form of, say, staghorn corals.

Heliofungia actiniformis. Photo by Samuel Chow, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Heliofungia actiniformis. Photo by Samuel Chow, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Instead most are free-living solitary polyps that grow to relatively enormous sizes. Heliofungia actiniformis (above) can reach 50 centimeters/20 inches in diameter. Believe it or not, the photograph above is of a single polyp.

Fungia fungia. Photo by Jon Zander, Digon3, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Fungia fungia. Photo by Jon Zander, Digon3, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Many mushroom corals look dead or bleached until their tentacles emerge, generally after dark.

Photo by Silke Baron, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Photo by Silke Baron, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

They share some interesting traits with their terrestrial (mostly) namesakes, the fungi, or mushrooms. Shape obviously. Though mostly it’s the juvenile fungiids, growing on stalks, that resemble terrestrial fungi. Sorry can’t find any pictures of them.

Lycoperdon perlatum. Photo by Dohduhdah, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Lycoperdon perlatum. Photo by Dohduhdah, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

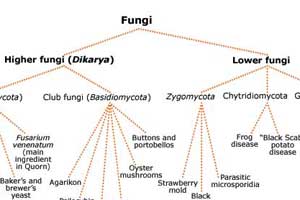

Mushrooms of the land are also amazing organisms. Enough so as to warrant a kingdom all their own, the Kingdom Fungi, separate from the plants, the animals (including mushroom corals), and the bacteria.

Photo by Dohduhdah, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.Genetically, mushrooms are more closely related to animals than plants.

Photo by Dohduhdah, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.Genetically, mushrooms are more closely related to animals than plants.

Portobello mushroom, Agaricus bisporus. Photo by Chameleon, courtesy Wikiemdia Commons.

Portobello mushroom, Agaricus bisporus. Photo by Chameleon, courtesy Wikiemdia Commons.

This seems pretty obvious to anyone who dines on mushrooms. A portobello—which is simply the older fruit, or pileus, of a button and a crimini mushroom—is downright meaty tasting. Photo by cyclonebill, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.Of late, a few discoveries about mushrooms are bending our notions of time and space in the living world.

Photo by cyclonebill, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.Of late, a few discoveries about mushrooms are bending our notions of time and space in the living world. Armillaria ostoyae. Photo by Eric Steinert, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Armillaria ostoyae. Photo by Eric Steinert, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

A clonal colony of honey mushrooms (Armillaria ostoyae) in Oregon has been found to extend across more than 965 hectares/2,384 acres of forested mountains.

The colony is estimated at between 1,900 and 8,650 years old.

The unreleased spores of a morel mushroom {Morchella elata} magnified 40 times. Photo by Peter G. Werner, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

The unreleased spores of a morel mushroom {Morchella elata} magnified 40 times. Photo by Peter G. Werner, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

The reproductive strategies of the Kingdom Fungi are equally exuberant. Many species reproduce sexually and/or asexually, depending on the stages of their life cycle and on environmental triggers.

In sexual reproduction, compatible individuals may combine by fusing their threadlike hyphae (the parts we usually don’t see, underground or inside rotting trees) together into an interconnected network. As if humans mated by first fusing our bloodstreams.

The video below highlights, with the help of lasers, tiny mushroom spores.

Secret Sounds of Spores: Introduction from The Amazing Rolo on Vimeo.

The second video is part of the same ongoing beautiful fusion of art and science hyphae. Wish I could get to Edinburgh to see the installation.

The Boroscilloscope from The Amazing Rolo on Vimeo.

The release of mushroom spores is spectacularly reminiscent of spawning corals.

In the photo below you can see the tiny orange eggs being released by a female mushroom coral (Fungia scutaria) spawning at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology in Oahu. Looks kind of psychedelic.

Photo by Dr. Dwayne Meadows. From the NOAA photo library.Photo by Dr. Dwayne Meadows. From the NOAA photo library.

Photo by Dr. Dwayne Meadows. From the NOAA photo library.Photo by Dr. Dwayne Meadows. From the NOAA photo library.

Researchers from Japan recently discovered that mushroom corals can change sex and back again, a talent known as sequential hermaphroditism. It’s not all that unusual in the deep blue home. Some of the echinoderms, like urchins and sea stars, along with some of the crustaceans, mollusks, and bristle worms gender shift every which way too.

In the mushroom corals studied so far, the smaller individuals are generally males and the larger individuals females. This makes sense when you consider the different time-and-energy investment required to make eggs versus sperm.

Mushroom corals, in their adult form, do have the ability to move, albeit very slowly, via three known mechanisms: by regulating buoyancy and floating away; by growing a hydromechanically adapted shape and floating away; or by creeping away. Motility enables them to seek out the sunniest locations on the reef—sunlight fuels their endosymbiotic bacteria—and to escape being overgrown by other corals.

But might they be sprightlier than we think? Recently mushroom corals living in the Gulf of Aqaba were observed eating moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita). How did they procure the wandering jellies? No one knows.

The papers:

- B. A. Ferguson, T. A. Dreisbach, C. G. Parks, G. M. Filip, and C. L. Schmitt. Coarse-scale population structure of pathogenic Armillaria species in a mixed-conifer forest in the Blue Mountains of northeast Oregon. Can. J. For. Res. 33(4): 612–623 (2003). DOI:10.1139/x03-065.

- Yossi Loya and Kazuhiko Sakai. Bidirectional sex change in mushroom stony corals. Proc Biol Sci B. 2008 October 22; 275(1649): 2335–2343. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0675.

- Alamaru, A.; Bronstein, O.; Dishon, G.; Loya, Y. Opportunistic feeding by the fungiid coral Fungia scruposa on the moon jelly?sh Aurelia aurita. Coral Reefs (2009) 28:865. DOI 10.1007/s00338-009-0507-7