Photo: Mark Murrmann

Editors’ Note: This education dispatch is part of an ongoing series reported from Mission High School, where education writer Kristina Rizga is embedded for the year. Click here to see all of MoJo’s recent education coverage, or follow Kristina’s writing on Twitter or with this RSS Feed.

[UPDATE: As expected, Gov. Jerry Brown proposed a budget today (pdf) that plans to keep California’s schools funded at the same dollar level, if—and this remains a big if, voters agree to a temporary tax increase.]

Mission High School Principal Eric Guthertz is back at school this week after the holiday break, and he has a lot on his mind. On Thursday, California’s new Superintendent of Public Instruction declared a state of emergency in schools; California, which educates one in eight public school children in America, is staring down a $28 billion budgetary hole. “We’ve made great progress in the last few years,” Guthertz says. “I worry what the cuts will do to that.”

Like most educators in the US, he has good reason to worry.

The recession “blew a huge hole in the already shaky finances of state governments,” notes Michael A. Fletcher at the Washington Post, and it’s only getting worse. States are now facing a 12 percent or greater decline in revenues from pre-recession levels, according to analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

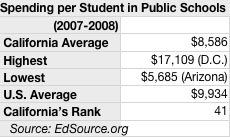

Since state and local taxes provide most of the funding for public schools, this is bad news, especially for the Golden State. California already spends less per student than nearly any other state, while working with the highest percentage of students learning English. And school budgets are heavily tied to state revenues thanks to Proposition 13, which slashed available property tax revenues by more than half since 1978, according to EdSource estimates. Last year, more than half of education funding came directly from the state.

Tom Torlakson, the new State Superintendent of Public Instruction, argues that there’s no more meat on the bone: California, which spends about $67 billion on its public schools, including all federal and local sources, has already cut 17 billion in the last two years. Many of the state’s school districts have already cut teaching materials, increased class size, and cut teachers, nurses, counselors, and psychologists. Some teachers buy supplies with their own money, share tips for donation websites, and clip coupons together in staff rooms.

This chilly austerity program translated into $113 million in cuts in the San Francisco Unified District—the home of Mission High. After months of negotiations between the district, the unions, and the community, the district laid off 200 teachers, shortened the school year, cut summer school and transportation for high schools, and reduced staff at central offices. Many schools also lost arts and sports programs. (pdf)

Last year, 13 teachers at Mission High got pink slips, Guthertz said, including the new music program director. (Mission High worked with the union to reinstate all positions later.) But thanks to the Quality Education Investment Act (QEIA)—a seven-year, $3 billion state program to help close the achievement gap in 500 low-performing public schools that educate high numbers of students of color, immigrant students, and low-income youth, Mission High has been shielded for two years from the worst cuts. Not only that, QEIA funds and other grants helped Mission High to reduce class sizes, increase the amount of common planning time among staff members, and add community liaisons like Linda Jordan, who works with the students and families of at-risk students to help improve their grades, stay in school, and make long-term career plans.

One recent afternoon, I stopped by Jordan’s office. Dressed in a long-sleeve Obama t-shirt, she was ordering Chinese take-out for three African-American students working on their summer internship job applications. A father walked in to talk to Jordan about his daughter’s declining attendance. “My wife and I live in different apartments now,” he said, looking distressed. His daughter must have found a loophole in the new situation, he concluded. “Don’t you worry,” Jordan responded with a big smile. “We are going to work it out. Step by step, inch by inch.”

Wouldn’t every school benefit from something like QEIA funding, a counselor like Linda Jordan, and more collective staff planning time?

Wouldn’t every school benefit from something like QEIA funding, a counselor like Linda Jordan, and more collective staff planning time?

Fortunately for Mission High, QEIA funding can’t be cut by the state, Mike Myslinski, the spokesperson for California Teachers Association, told me. But this funding is only a small slice in the total funding pie (about $500 per student), and it won’t be able to shield Mission High and the other 500 lowest-achieving schools that receive such funding from the looming budgetary blow this year.

So, Governor Jerry Brown is planning to ask voters to make some difficult decisions in a special election in June. This week, The Sacramento Bee reported that the governor plans to spare K-12 education and community colleges from further cuts. But only if—and this is a big if—California voters agree to higher taxes on their purchases, cars, and income. Without those additional taxes, the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office projects that 2011-12 will be the worst year for schools in the current slump.

So far, Americans have said that they like the generous services government provides, but don’t want to pay higher taxes. That worked well enough when the Internet and house booms fueled revenue streams, but now? It’s time for some very painful choices. Less services. Or more taxes? As California goes, so goes the nation.