Something perhaps obvious but still unexpected that I learned this week: Kneeing somebody in the balls as hard as you can 47 times makes your thigh sore. But it’s important to do it as repeatedly as possible. The more you practice it, the easier it—and asking someone not to get in your face and sounding like you mean it, and dropping someone to the floor with an elbow across his jaw—gets.

Something perhaps obvious but still unexpected that I learned this week: Kneeing somebody in the balls as hard as you can 47 times makes your thigh sore. But it’s important to do it as repeatedly as possible. The more you practice it, the easier it—and asking someone not to get in your face and sounding like you mean it, and dropping someone to the floor with an elbow across his jaw—gets.

There are six physiological responses to crisis: flight, fight, freeze, collapse, disassociate, hypervigilance. Freezing is incredibly common. It is, in fact, the reason the “full-force” personal safety course I started on Sunday was invented. Its founder is a black belt in karate who was stunned to find, one horrible day, that when it came down to it, she couldn’t defend herself against being beat up and raped. She was an expert at fighting—in theory. All the highly skilled kicking and chopping she’d done had been in controlled spars, not under the influence of survival adrenaline, which can overwhelm cognitive function. The 13 women between the ages of 20 and 60 who were at the Oakland dojo with me either have had a similar paralysis or anticipate they might if something bad went down. They enrolled in this Impact Bay Area training because they want to practice deescalating threatening situations and, in case that doesn’t work, fighting a way out of violent ones. They came because they want to feel safer in general or have a better chance next time. Or because, let’s say, they went to Haiti for a reporting assignment and disassociated while watching a recent rape victim have a screaming meltdown and/or froze while being dangerously harassed, then came home and were diagnosed with PTSD and couldn’t get out of bed for kind of a long time, and are addressing their own and their editors’ preference that they have more on-the-ground crisis-coping tools before soon being dispatched to the rape capital of Africa.

You cannot stop your instinct to freeze. But according to the philosophy of Impact, which has chapters in ten states and four countries, you can, with practice, learn to move on from it in about a second. “Impact was created from research into how women are actually attacked,” the website says. “Impact provides real practice.”

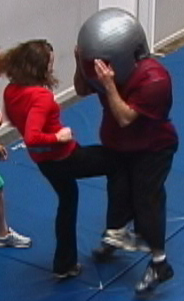

Practice, in this case, involves spending three Sundays in a row with a guy wearing an extraordinary amount of padding. This is not the light play-acting assault you did in your self-defense elective in college. This is a guy approaching you in front of a bunch of other people and exploiting your socialization to be nice to cross your boundaries, get into your personal space, keep talking to you even after you’ve tried to make it clear you aren’t interested. This is a guy stalking around chatting you up and sometimes refusing to take no for an answer when you try to end a conversation. This is also a guy sometimes coming at you from behind and tackling you to the floor. Or coming at you from the front. Or attacking you from the side or by grabbing hold of your hair. Practicing “full-force” defense means that you are not allowed to pull your punches or just mimic your way out; this assailant will fight you until you’re striking him as hard as you actually can and he thinks he could’ve been legitimately knocked out if not for the padding. Or until you call a safety word (in this class, no one ever did). Until then, the fight continues, whether very bad memories are coming up and overwhelming you or not. At one point in the afternoon, those of us whose turn it was to not be assaulted winced as we watched our assailant drag a sobbing girl kicking and screaming to the ground.

If that sounds like the worst thing you could voluntarily do with a day, that’s because it really is. But though we were unnerved, and uncomfortable, and unhappy, it was all in the name of learning options. If your emotional or personal space is being violated, saying “I’m not interested” or “No” is actually a really good one, if you can make it come out of your mouth without a polite smile or adding a “thank you” or even “sorry”—which, if you’ve been raised as a girl, you probably can’t, without practice. But if your physical space is violated? When you’re grabbed in a heavy bear-hug, you can swing a punch behind you to the groin, extend your arm and slice it back for an elbow to the solar plexus, extend again but palm down for the windup to a backwards elbow across the face. If you’re face-to-face and have already thrown a palm into his nose to no avail, you better make sure you slam your knee up into his crotch as hard as if you’re aiming to bust all the way through to his chin. If he takes you by the throat, drop out of it, fast to the ground, and land strategically on your hip with one leg cocked to deliver dick- or chest-blows. Etc.

One of the keys, obviously, is to act fast. And the more practice you have being assaulted, the faster you can react. That’s why at Impact they terrorize you for eight. Hours. Straight. Until your body performs the physical and verbal drills automatically. Until your body has broken the bad habit of not yelling at dudes who are being assholes. Until your body isn’t so shocked by a physical attack that you can instantly respond by basically turning into a ninja.

And respond you eventually do! With two calm potheads for parents, I was never exposed to or developed a tolerance for so much as being yelled at. But even this extremely conflict-averse 125-pound girl, even through the exhaustion of many highly adrenalized hours in a screaming-and-assaulting environment, could by the end of the day drop the assailant in two blows in about five seconds, even when the timing and style of the assault were a surprise. For the last two decades, Impact has run a training program down south in Monterey. Eight hundred women have been through the program. Fifteen of them have since been assaulted; all 15 won the fights their assailants started.

Sunday’s class was just the first day of the basics training. After the whole course is completed, you can take the knife- and gun-fighting course. But for us rookies, up next week: much more intensive verbal deescalation drills, including setting boundaries with people who aren’t strangers. Also: customized assault, in which Impact reenacts your personal worst nightmare attack. But even after just one day, everyone was feeling, despite the bruises and fatigue, a lot tougher. “Now I know that if I got attacked, I would definitely fight back,” one of the gals who’d earlier said she couldn’t even scream said before we left. “I don’t know if I’ll win. But at least I know I’ll do something.”