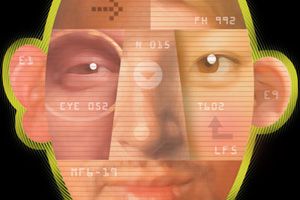

Illustration by Gordon Studder

UPDATE: Stranded travelers could face a new homeland security toy this week. On Tuesday, the Transportation Security Administration announced that it’s begun “testing new software” on select airport body-scanning machines in Las Vegas, Atlanta, and Washington DC. The new imaging technology “auto-detects” suspicious material, boosting privacy by presenting potential threats on a generic human outline rather than a passenger-specific image. “If no potential threat items are detected, an ‘OK’ will appear on the monitor,” notes the TSA press release.

IF YOU’RE UNHAPPY with the choice between having the Transportation Security Administration “porno-scanning” you or touching your junk, this might also freak you out: The TSA is trying to read your mind. Since June 2003, it’s been monitoring travelers’ facial expressions and body language for signs that they might be hiding something. As of March 2010, the TSA’s Screening Passengers by Observational Techniques (SPOT) program had 3,000 “behavior detection officers” in more than 150 airports. Their job is to strike up conversations with passengers at security checkpoints, checking for what one TSA official describes as “behaviors that show you’re trying to get away with something you shouldn’t be doing.” People who don’t display “normal airport behavior” may be stopped for questioning.

SPOT is based largely on the work of Paul Ekman, a behavioral scientist who has spent his career identifying “microexpressions”—twitches lasting between one-fifteenth and one-twenty-fifth of a second that reveal intentionally concealed emotions. Ekman’s methods have been used by the animators of Toy Story and Shrek and celebrated by Malcolm Gladwell, and they inspired the Fox TV series Lie To Me, whose main character is a human lie detector who thrives on confrontations with psychopaths and murderers. That’s a far cry from Ekman himself, an unassuming 77-year-old who makes no claims of infallibility. “I’m never absolutely certain,” he says, sitting in his San Francisco loft. “I can’t tell you what triggers an emotion. I can only tell you to recognize an emotion even when someone doesn’t want you to recognize it.” Nonetheless, he says that had he been stationed at an airport security checkpoint on the morning of September 11, 2001, he probably could have plucked Mohamed Atta out of a crowd.

In the real world, the TSA’s behavior detection officers have yet to make such a dramatic catch. Of the 2 billion passengers who traveled through airports where the behavior-scanning program was deployed between 2004 and 2008, 152,000 were flagged for further examination. Of those, fewer than 1,110 were arrested. Most were undocumented aliens, had outstanding warrants, or were carrying fake documents or drugs. In April 2008, SPOT officers stopped an Army vet carrying bomb-making supplies at the Orlando airport. Beyond that, SPOT has not reported its agents picking out any other people identified as would-be terrorists. In reviewing the program, the Government Accountability Office concluded that “a scientific consensus does not exist on whether behavior detection principles can be reliably used for counterterrorism purposes.”

But the TSA already has plans for taking its face-scanning program high-tech. It’s sunk $20 million into developing Future Attribute Screening Technology, a computerized version of the behavior-observation system that will use cameras to scan travelers’ expressions and match them with a digital database of microexpressions.

That, Ekman says, is where the government might be taking things too far: “Don’t try to get the human out of the system,” he warns. He recalls how, while training officers at Boston’s Logan International Airport, he helped question a man who’d been acting erratically. It turned out the passenger’s brother had just died and he was flying home for the funeral. A machine might have labeled the grieving man as a security threat, but Ekman got to the truth more efficiently and personably.

The ACLU has also criticized the TSA’s face-scanning efforts as pseudoscientific and possibly unconstitutional. Security expert Bruce Schneier, a longtime critic of airport security, thinks terrorists will try to outsmart the system: “We do this Ekman stuff, and the bad guys recruit people who don’t show emotions.”

Just how hard is it to fool a face scanner? Consider this: Before I met Ekman, he asked me to look up someone who used to be connected to Mother Jones. The request slipped my mind, and when he reminded me about it in person, I stuttered before fibbing that I hadn’t heard back from his acquaintance. If Ekman sensed my lie, he let it slide.