Correction: Yikes. As some commenters noted, I blundered by attributing the energy losses shown in the chart below entirely to electricity lost during transmission. That was careless, and I’ve corrected it below. In fact, a lot of the losses are due to heat lost in the generation process. Transmission losses, as the fine print indeed noted, were estimated at 6.5 percent. On the other hand, that’s still an enormous amount of lost power. In retrospect, I guess I’d have to agree with the commenter who says we need a mixture of distributed and centralized power to meet our needs. But I still contend that utilities have actively resisted distributed power generation, and that’s counterproductive. What’s more, companies need to do more to reduce heat losses. Here’s a great piece from the Atlantic on that very topic.

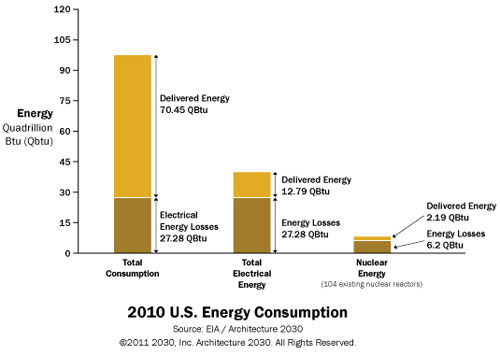

In response to Japan’s nuclear crisis, the US green-building group, Architecture 2030, sent out a couple of emails last week fact-checking media assertions that nuclear power accounts for roughly 20 percent of US energy consumption. In fact, the group points out, nuke plants provide about 21 percent of US electricity consumption, but less than 9 percent of overall US energy consumption.

It’s a wonky distinction, but the accompanying chart shows something more striking, in case you didn’t know it: The way we make and deliver electricity is incredibly inefficient. “Electricity consumption,” in utility jargon, is the sum of the power we actually use plus the power lost as heat during generation and transmission of electricity through cables to our homes and businesses. If you were to completely ignore this massive waste, nuclear accounts for just 3 percent of actual energy use, and 17 percent of actual electricity use.

The chart above suggests that just 26 percent of nuclear-generated electricity makes it to customers, versus 32 percent for all generation sources combined. And that’s before factoring in the staggering capital costs (requiring tens of billions of dollars in federal loan guarantees), the very scary problem of what to do with spent fuel rods (which has also sucked up billions of tax dollars), and the fact that the US government has had to insure the nuclear industry against disasters because no private company will assume that risk.

In essence, this chart is a reminder that we would benefit from a big increase in distributed power generation—a fancy way of talking about electricity produced at small facilities closer to where it’s used, rooftop solar being the ultimate example. Trouble is, the private utilities that own the reactors and coal plants and gas turbines (as well as many transmission lines) have fought tooth and nail to shut smaller companies and residential power generators out of the grid. After all, they wouldn’t want their Edsels to lose value.