The “Baker” explosion at Bikini Atoll, Micronesia, on 25 July 1946. Credit: US Navy, via Wikimedia Commons.

The “Baker” explosion at Bikini Atoll, Micronesia, on 25 July 1946. Credit: US Navy, via Wikimedia Commons.

1) Nuclear weapons tests:

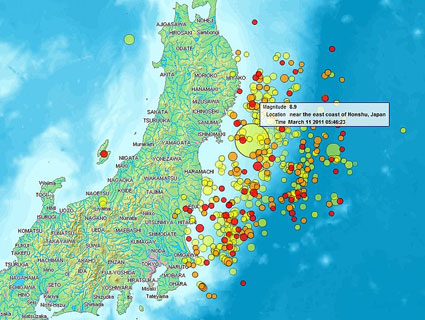

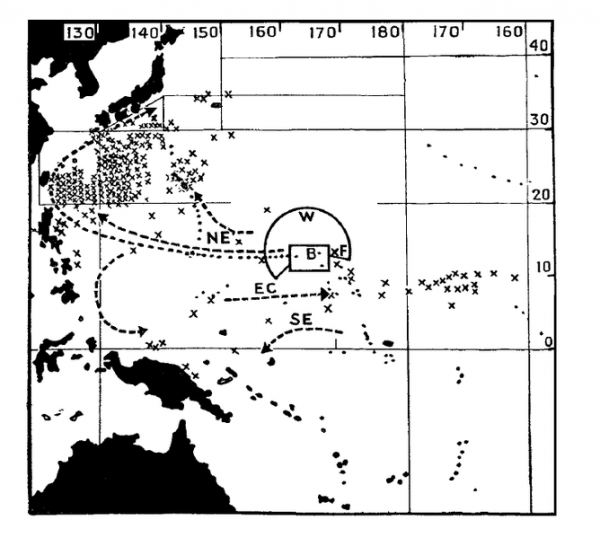

- For example, at Bikini Atoll between 1946 and 1958, the US detonated 23 atmospheric nuclear bomb tests, including the first hydrogen bomb, which exploded far more violently than predicted and contaminated a swath of ocean 100 miles/160 kilometers away from the epicenter. The fallout affected inhabited islands, fishing boats and fishers at sea, and, obviously, a lot of marine life. The map below shows where contaminated fish were caught, or where the sea was found to be excessively radioactive, after the 1955 hydrogen bomb test at Bikini=X marks. B=original “danger zone” announced by the US government. W=”danger zone” extended later. NE, EC, and SE are equatorial currents. Credit: Y. Nishiwaki, 1955, for the government of Japan, via Wikimedia Commons

Credit: Y. Nishiwaki, 1955, for the government of Japan, via Wikimedia Commons.

Credit: Y. Nishiwaki, 1955, for the government of Japan, via Wikimedia Commons.

- France exploded 193 nuclear tests in the atmosphere and in the waters of French Polynesia between 1966 and 1996. The tests began after the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty outlawing detonations in the air. I wrote about this in my book THE FRAGILE EDGE:

The [first] bomb was exploded aboard a barge in the [Moruroa’s] lagoon, sucking water into the air and raining dead ?sh, corals, cephalopods, crustaceans, mollusks, and all the once living components of the reef onto Moruroa’s motu [islands], where their radioactive forms decayed for weeks. Confounded by this result, the French hastily arranged to explode their second bomb seventeen days later from an air plane 45,000 feet above the featureless South Pacific, some 60 miles south of Moruroa. Without people or equipment to witness, record, or analyze this distant blast, virtually no data was collected, making its detonation more an act of pique than science. Two days later, as described by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists:

An untriggered bomb on the ground [at Moruroa] was exposed to a “security test.” While it did not explode, the bomb’s case cracked and its plutonium contents spilled over the reef. The contaminated area was “sealed” by covering it with a layer of asphalt.

Top: Moruroa Atoll. Bottom: Fangataufa Atoll, French Polynesia, sites of French nuclear tests. The dark blue waters in the upper lagoon of Fangataufa mark the deep crater created by bomb explosions. Credit for both: NASA, via Wikimedia Commons.

Top: Moruroa Atoll. Bottom: Fangataufa Atoll, French Polynesia, sites of French nuclear tests. The dark blue waters in the upper lagoon of Fangataufa mark the deep crater created by bomb explosions. Credit for both: NASA, via Wikimedia Commons.

- So far, eight nuclear-powered submarines have sunk or been scuttled: two American, four Soviet; two Russian.

- Four in the North Atlantic, three in the Barents Sea, one in the Kara Sea north of Siberia.

- Another accident in 1968 in the North Pacific 1,796 miles / 2,890 kilometers northwest of the Hawaiian island of Oahu led to the sinking of a diesel-electric Soviet sub sank carrying nuclear ballistic missiles.

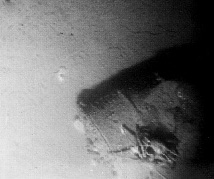

Salvaged wreck of the Russian nuclear submarine K-141 Kursk, via Wikimedia Commons

Salvaged wreck of the Russian nuclear submarine K-141 Kursk, via Wikimedia Commons

- The launch failure in 1964 of an American navigation satellite with an onboard radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG)—an electrical generator fueled by radioactive decay. This fell into the ocean near Madagascar and deposited a quantity of plutonium-238 equal to half the amount of plutonium-238 naturally present in the entire World Ocean.

- The failed Apollo 13 mission (1970) jettisoned its Lunar Module Aquarius with the intention that it would crash into the sea and plummet into the Pacific’s Tonga Trench—one of the the deepest places on our planet—since it was still carrying its RTG with plutonium dioxide fuel. So far no plutonium-238 has been recorded in nearby atmospheric and seawater sampling, suggesting the cask is currently intact on the seabed.

- At least four other RTG-powered spacecraft have fallen to Earth, including one into the waters of the Santa Barbara Channel off California in 1968.

- Between 1973 and 1993, at least five Soviet/Russian RORSAT satellites failed to eject their nuclear reactor cores prior to falling back to Earth. One fell into the Pacific north of Japan (1973), another over Canada’s Northwest Territories (1978), another in the South Atlantic (1983). The successfully ejected cores are in still orbit, destined to plummet back to Earth someday.

The Apollo 13 Lunar Module, Aquarius, just after jettisoning on 17 April 1970. Credit: NASA, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Apollo 13 Lunar Module, Aquarius, just after jettisoning on 17 April 1970. Credit: NASA, via Wikimedia Commons. - Britain’s Sellafield (aka Windscale) is a nuclear storage site, an erstwhile nuclear weapons production plant, nuclear reprocessing center, and nuclear power plant, currently in the process of decommissioning. Due to accidents, chronic emissions, and overflows at Sellafield, the nearby Irish Sea is deemed the most radioactive sea on Earth.

- The Hanford Site in Washington—home to the world’s first plutonium production reactor—purposely released radionuclides down the Columbia River from the 1940s to the 1970s. The contamination travelled hundreds of miles into the Pacific Ocean. Today the radionuclides are used as markers by oceanographers tracking sediment movements on the continental shelf.

Salmon spawning in the Hanford Reach of the Columbia River, at the site of 30 years of radioactive releases. Credit: US Department of Energy, via Wikimedia Commons.

Salmon spawning in the Hanford Reach of the Columbia River, at the site of 30 years of radioactive releases. Credit: US Department of Energy, via Wikimedia Commons.- Dump sites for radioactive waste were created in the northeast Atlantic (1 site), off Europe (3), off the US eastern seaboard (1), and off the US Pacific coast (1).

- Between 1946 and 1970, the US dumped ~107,000 drums of radioactive wastes at its two sites, including some 47,800 in the ocean west of San Francisco, supposedly at three designated sites. However drums actually litter an area of at least 1,400 square kilometers/540 square miles, known as the Farallon Island Radioactive Waste Dump, which now falls almost entirely within the boundaries of the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. The exact location of most drums is unknown. At least some are corroding.

A drum of radioactive waste dumped off San Francisco. Credit: USGS.

A drum of radioactive waste dumped off San Francisco. Credit: USGS.

Concentrations of both [plutonium-238] and [Americium-241] in fish tissues were notably higher than those reported in literature from any other sites world-wide, including potentially contaminated sites. These results show approximately 10 times higher concentrations of [plutonium-238+240] and approximately 40-50 times higher concentrations of [plutonium-238] than those values reported for identical fish species from 1977 collections at the [Farallon Islands Nuclear Waste Dump Site].