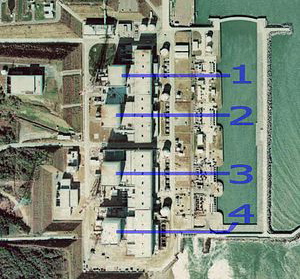

Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant before the tsunami. Credit: Japan Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, via Wikimedia Commons.

A survey of developments in light of Japan’s triple disasters: earthquake, tsunami, nuclear.

The New York Times reports the chairman of the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission views Japan’s nuclear problems far more bleakly than Japan, advising that because radiation levels are “extremely high” Americans should evacuate to a 50-mile radius from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Japan has imposed an evacuation order only to a 12-mile radius, and a shelter-in-place suggestion within a 12- to 18-mile radius.

The Environmental News Network notes that the massive amounts of seawater workers are pouring onto Fukushima’s failing nuclear reactors and cooling ponds are afterwards flushing into the sea, presumably laden with a variety of radioactive isotopes.

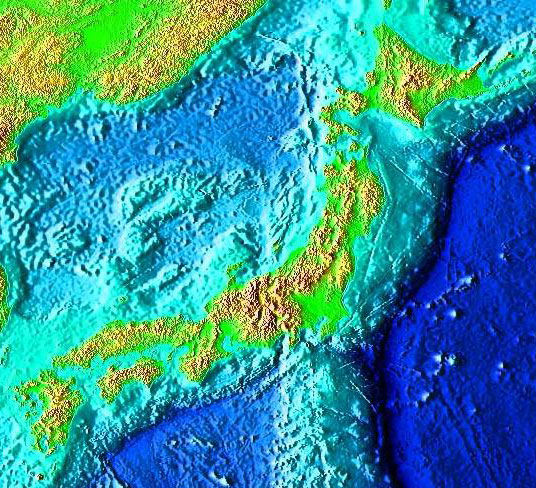

On the tsunami front, the New Zealand Herald reports that tsunami waves hit every single beach and coastline in New Zealand, in places doubling wave heights. The first wave arrived 12 hours after the quake. The largest swells hit 45 to 52 hours after the quake. Even now, days later, New Zealand is recording leftover waves affecting currents in harbors and estuaries. These 6-day-old swells are the echoes of tsunamis continuing to bounce off continental shelves and coastlines around the entire Pacific Ocean basin all the way down to Antarctica.

The Honolulu Star-Advertiser reports that tsunami waves devastated seabird breeding rookeries on Midway Atoll in the northwestern Hawaiian Archipelago, killing tens of thousands of Laysan albatross, including adults and their chicks. The adults died because they don’t easily abandon their chicks, and because it takes an albatross a long time to lumber across the water and get airborne. More on that in an upcoming post.

Laysan albatross chicks and a few parent birds. Credit: Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Mark Logico, US Navy, via Wikimedia Commons.

Laysan albatross chicks and a few parent birds. Credit: Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Mark Logico, US Navy, via Wikimedia Commons.

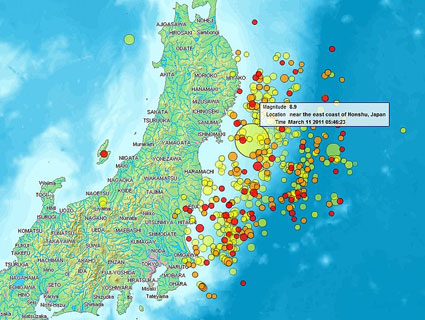

On the earthquake front, Nature News reports on the surprise among researchers of a 9.0 temblor off Sendai:

[G]eophysicists had thought that great subduction-zone earthquakes happened only where younger oceanic crust scrapes its way into the mantle. Older crust, which is cooler and denser, was thought to slide much more readily downward, triggering smaller quakes. And the ocean crust off the northeast part of Japan, having formed about 140 million years ago, is about as old as it can get.

The Great Sumatran Earthquake of 2004 also appeared to negate the sea-floor-age hypothesis, since old subducting crust there in no way hampered a 9.1 quake. In the case of Sendai, recent data suggest the area’s getting squeezed, that the Pacific plate was stuck and released in a giant lurch.

The Japanese Islands are situated along a line to the west of the Japan Trench. Credit: NOAA, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Japanese Islands are situated along a line to the west of the Japan Trench. Credit: NOAA, via Wikimedia Commons.

New Scientists reports on how Japan’s ultra-advanced seismic monitoring system gave them speedy information—too speedy, it turns out:

Japan has a network over 800 seismic monitoring stations called Hi-net that can detect everything from the faintest tremor to the biggest temblor. It works almost too well… on Friday the Japan Meteorological Agency issued an initial warning on its website that a magnitude-7.9 quake had struck off the coast of central Honshu island. The quake ended up far bigger, but the warning came before the fault had even finished breaking.

The problem was it took about 3.5 minutes for more than 248 miles of the Japan trench to finish rupturing. The warning bells sounded too soon. Of further interest: Why do these quakes break as they do? Why not stop at a 100-mile rupture and a smaller than 9.0 magnitude? Or why not carry on for over 620 miles, as did the 2004 Sumatra quake? It’s still a mystery.