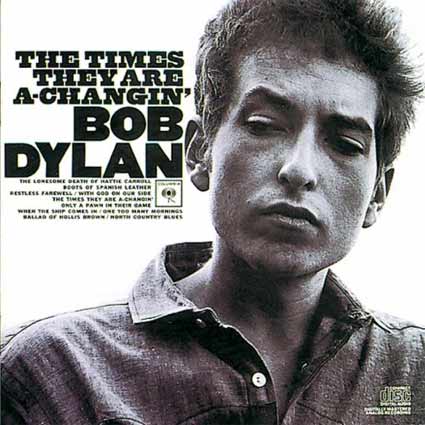

Last Sunday, Bob Dylan played a show in Vietnam for the first time in his half-century long career. The tickets didn’t sell well. Only half of the venue’s 8,000 seats were filled when Dylan took the stage in his white cowboy hat and performed for two hours, ending the night with his 1974 hit “Forever Young.” As with Dylan’s two previous shows in Beijing and Shanghai, his omission of protest songs like “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “The Times They Are a-Changin’” was met with anger from Human Rights Watch and columnists like Maureen Dowd.

“The idea that the raspy troubadour of ’60s freedom anthems would go to a dictatorship and not sing those anthems is a whole new kind of sellout,” she wrote of the China performances last week. “Sellout,” of course, implies that Dylan traded some measure of his artistic integrity for profit on his tour of Asia. While he may have consciously neglected his protest songs, it’s hard to imagine he did it to earn a few bucks.

The whole concept of selling out never had much play with Dylan. In the 1960s, he told a reporter he would sell out to do a ladies undergarment ad— and 40 years later he appeared in a Victoria’s Secret commercial singing, “I’m sick of love, but I’m in the thick of it. This kind of love, I’m so sick of it.“

That joke has too long a wind-up to come from a man with no integrity. His choice not to perform the protest songs in China that he wrote during the American Civil Rights Movement reflects more than anything an honesty with himself about his place as an artist. Activism is a lifestyle. He doesn’t perform at marches and rallies anymore or write topical songs like “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll.” He hasn’t been that Bob Dylan for a long time.

Nor has anyone thought otherwise: Much of what he has written since the mid-1980s has been called second-rate. Those who complain that Dylan should speak out against human rights violations in China mock his fading voice in the same breath. His songs these days are about being rich, lonely, love-sick, and near death. (In 2001, he sang, “I’m driving in the flats in my Cadillac Car, the girls all say, ‘You’re a washed-up star.” But my pockets are loaded and I’m spending every dime.“) If he ever was a protest singer, he’s not so anymore. Not playing “Blowin’ in the Wind” isn’t selling out; it’s just Dylan’s way of reminding us of something we already know: China and Vietnam might need a Bob Dylan, but they don’t need him.

Consider how other artists have reconciled their music with old age. When Neil Young was 30, staying up all night in a windowless recording studio writing Wild Turkey-fueled songs, he sang, “I’m singing a borrowed tune, I took from the Rolling Stones. Alone in this empty room, too wasted to write my own.” When he was married, 55, and raising his kids, he sang, “Our kind of love never seems to get old. It’s better than silver and gold.“

Tom Waits started out writing about 3 a.m.s falling in love with the last girl at the bar. “I wanted to experience what it was like to be on the road the way I imagined it would be for all the old-timers that I loved, so I would stay in these down-joints because I was absorbing all the atmosphere in those places, the ghosts in the room,” he said of his early days in Los Angeles. When the life got to be too much, he quit his hard drinking, got married, moved to New York and he abandoned his barroom sound. Dylan could no more be a protest singer forever than Young could stay a rock-and-roll kid or Waits an LA barfly. In 2004, in one of the few interviews Dylan has given since the 1960s, he told the late Ed Bradley, “You feel like an impostor when people think you’re something and you’re not.”

It’s hard to know exactly when Dylan first realized he wasn’t going to be a protest singer like Woody Guthrie. Perhaps it happened around the time he exchanged his work pants and collared shirts for leather shoes and dark sunglasses and plugged in his electric guitar. In any case, Dylan explained his transformation to Bradley in this way: “Those early songs were almost magically written,” he said. “Try to sit down and write something like that. There’s a magic to that, and it’s not Siegfried and Roy kind of magic, you know? It’s a different kind of a penetrating magic. And, you know, I did it. I did it at one time…and I can do other things now. But, I can’t do that.”

Imagine our Minnesota poet cowboy—who first came down from the North Country to sing Woody Guthrie songs 50 years ago, who landed a record deal after less than a year performing in Greenwich Village, who played when Martin Luther King Jr. talked about his dream, who realized folk singers were “a bunch of fat people” and then picked up an electric guitar at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival and performed what would later be named the greatest rock-and-role song of all time, and who, in 2008, was given a special citation by the Pulitzer Prize committee for his “profound impact on popular music and American culture”—imagine him for the first time sitting on stage in Vietnam War-battered Ho Chi Minh City, almost 70 years old, grumbling his way through unrecognized new material and unrecognizable arrangements of old favorites to a half-empty room of 4,000 aging Vietnamese.

The scene of this tired singer reminds me of an episode of the television show “The Wonder Years.” Kevin, the adolescent main character, decides to quit playing the piano. As he stands outside his teacher’s house, a narration by his older self reflects on the moment: “When you’re a little kid, you’re a little bit of everything—artist, scientist, athlete, scholar. Sometimes it seems like growing up is a process of giving those things up.” Bob Dylan may have started out a protest singer and a folk artist. But he gave that up a long time ago. “Forever Young” was a more apt closing song than “Blowing in the Wind” would have been.